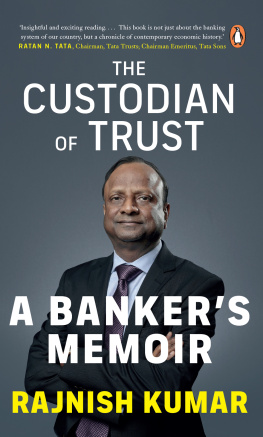

To the teachers of St. Xaviers School, Doranda, Ranchi,

who taught me to read, write and

understand the power of compounding

Garib lehron par pehren bithaye jaate hain samundaron ki talashi koi nahi leta.

Waseem Barelvi

Contents

John Maynard Keynes, an oft-quoted but less-read economist, who lived in the first half of the twentieth century, is said to have remarked: If you owe your bank a hundred pounds, you have a problem. But if you owe your bank a million pounds, it has.

The Economist, which likes to call itself a newspaper, but is actually a magazine, a few years ago came up with the modern-day version of what Keynes had said: If you owe your bank a billion pounds everybody has a problem [emphasis added].

Over the last decade, Indian banks have seen a major growth in their non-performing assets, or bad loans as they are more popularly known. Bad loans are largely those which havent been repaid for a period of ninety days or more.* As of 31 March 2018, the bad loans of Indian banks amounted to more than Rs 10,36,187 crore. The bulk of these bad loans was with the government-owned public sector banks (PSBs) and amounted to Rs 8,95,601 crore. As of 31 March 2019, the overall bad loans of banks had fallen to Rs 9,36,474 crore and that of PSBs had fallen to Rs 7,89,569 crore.

These bad loans had accumulated because of large defaults made by corporate borrowers the biggest of them being Bhushan Steel, which had defaulted on over Rs 56,000 crore. There were many other such borrowers who had defaulted on bank loans. Defaults on loans made to industry (also referred to as corporate defaults) made up for nearly three-fourths of the overall loan defaults. All this money, if it had been utilized well, could have been put to some good use. It could have helped build better physical infrastructure and more factories in the country. This would have created more jobs, which the country badly needs, given its burgeoning demographic dividend, and, in turn, benefited many individuals. The spending by these individuals could have benefited businesses and, in the process, unleashed a period of high and sustainable virtuous cycle of economic growth. This could have quickly pulled many millions of Indians out of poverty. But it ended up being wasted. In the process, good money of bank loans became the bad money of the Indian financial system.

And because of this good money turning into bad money, everybody had a problem. This book deals with precisely that point of everybody having to face a problem because banks and, in particular, PSBs, ended up accumulating bad loans.

The book starts with how corporates ended up taking on massive amounts of loans in the years 2003 to 2008, when the going in the Indian economy was good and the assumption was that the fast economic growth would last forever.

But the financial crisis of 2008 played spoilsport. Nevertheless, PSBs were encouraged to lend in the aftermath of the financial crisis and corporates kept borrowing.

Sometime in 2011, the situation changed, from one of over-optimism to one of pessimism. Corporates had overborrowed and banks had overlent. Corporate projects did not start on time due to a whole host of factors from a lack of environmental clearances to a lack of non-environmental clearances to problems with acquiring land to roadblocks on policy issues, as well as the inability of the promoters of projects to bring in their fair share of capital to the projects.

Very soon, the steel cycle had turned from positive to negative and steel companies were staring at massive overproduction. This was true of the power sector as well, which ended up with massive overcapacity, particularly in thermal power. Thermal power needed coal and Coal India, Indias major coal producer, couldnt supply the required amount.

Banks could have carried out a mid-course correction at this point. They could have stopped lending to corporates and limited the amount of bad loans they would end up accumulating. But that did not happen. Banks, specially PSBs were happy to restructure loans by increasing the tenure of the loan or decreasing the interest rate charged on it. In some cases, new loans were also given so that corporates could repay the old loans which were due. The idea was to not recognize bad loans as bad loans, but simply kick the can down the road for someone else to deal with.

A major question that the book tries to answer is on crony capitalism and what sort of role it played in the accumulation of bad loans. Was it the main reason behind the accumulation of bad loans or is there much more to the issue than just this?

Meanwhile, as all of this was happening, the banking regulator, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), simply looked the other way. This changed in mid-2015, when Raghuram Rajan, the RBI governor between September 2013 and September 2016, launched an Asset Quality Review of banks and, in the process, forced them to recognize bad loans as bad loans. But even this did not bring out in the open the correct picture of the bad loans of the banks.

Urjit Patel, Rajans successor as the RBI governor, put out a circular on 12 February 2018, which quashed all the schemes banks were using to restructure bad loans, and this forced them to recognize more bad loans. But are the banks done recognizing bad loans as bad loans? The jury is still out on that.

In economics, there is no such thing as free lunch for someone has got to bear the cost. As the bad loans of PSBs accumulated and losses mounted, the government had to constantly invest more money in these banks to keep them going. Between 201112 and 201819, it invested Rs 2,91,504 crore to keep these banks afloat. The bulk of this, Rs 90,000 crore and Rs 1,06,000 crore, were spent in 201718 and 201819 respectively. It plans to spend another Rs 70,000 crore in 201920 to continue to recapitalize these banks and keep them going. Between April 2019 and mid-November 2019, the government had invested Rs 55,757 crore in these banks. If we include IDBI Bank, which is no longer a PSB, but used to be one, the number goes up to Rs 60,314 crore.

All this money, which is going into the banks could have easily gone somewhere else. Also, who is paying for this mess? The taxpayer and the investors of the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) of India and, as you shall see in this book. Its happening in ways we dont even realize.

There are other costs that come attached to this as well. Banks have jacked up interest rates to levels which they wouldnt have if they were not facing this massive problem of bad loans. And this has made the monetary policy of RBI ineffective.

An important point discussed throughout this book is the faith that the Indian depositor has in PSBs. Despite a few banks having a bad loans rate of more than 20 per cent, which means more than a fifth of the loans they have given out have been defaulted on, a large chunk of depositors continue to maintain their deposits with these banks and have not withdrawn them. At least, theoretically, some of these banks should have seen massive bank runs, but they didnt. And this helped them to keep going. It also ensured that the problem did not turn into a massive financial headache for the government and it could deal with it on a year-to-year basis.

And of course, towards the end, the book also offers solutions on how to ensure that this problem does not happen all over again. Thats what Bad Money is all about.

The book is divided into two parts. Part I sets the context of the book and deals with some of the history of Indian banking, which is important in order to understand the bad loan crisis. The history essentially explains government control over PSBs and how it has ended up hurting these banks over the long term. Indias banking history also explains why depositors continue to have faith in PSBs, despite the high number of bad loans these banks have on their books. Part II deals with the actual crisis; the how and the why of it.