The Complete Works of

EDWARD GIBBON

(1737-1794)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2015

Version 2

The Complete Works of

EDWARD GIBBON

By Delphi Classics, 2015

The History

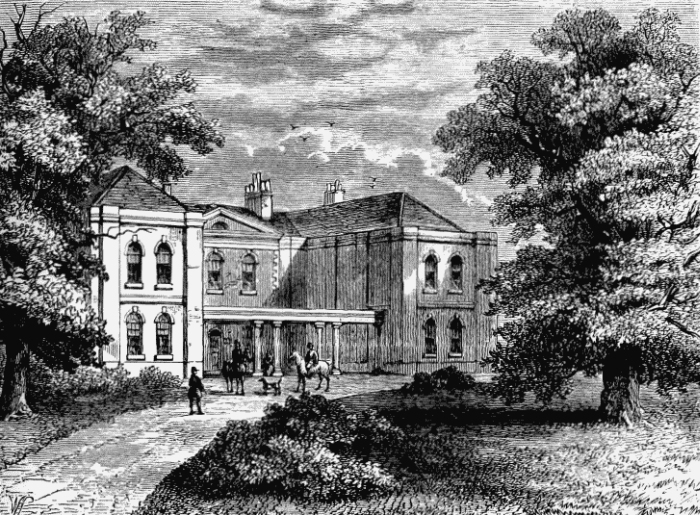

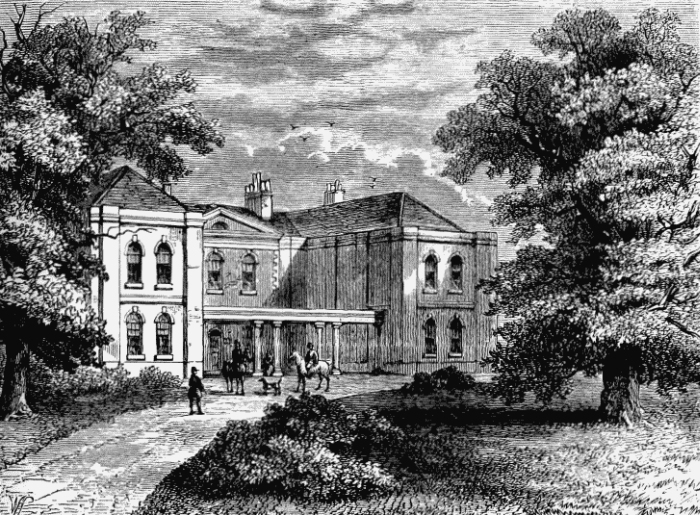

Lime Grove, Putney, Surrey Gibbons birthplace. Here Gibbon spent his holidays whilst at school, until the house was broken up on his mothers death, when he was twelve years old.

THE HISTORY OF THE DECLINE AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

This gargantuan work began as a resolve by Gibbon in 1764 to write a history of the city of Rome and later it grew into the much wider project he was to eventually publish. Although Gibbon was a gentleman scholar with a passion for history, the project did not run smoothly at first; numerous re-writes, including three different first chapters were undertaken and Gibbon declared that he was often tempted to cast away the labour of seven years. Of course he did no such thing, but it was not until 27th June 1787, between the hours of eleven and twelve in the evening and sitting in the summer house in his Swiss garden, that Gibbon wrote the closing words of Decline and Fall. He later recalled his understandable feelings of elation at its completion, expressing a feeling of loss that the work that had preoccupied him for so long had now ended. By this time Gibbon already knew that the work was successful, because of the reception of previous volumes already published, so he was confident that his final volume would be equally popular. The last volume was published in 1788.

One can hardly blame Gibbon for taking pleasure in the dramatic success of his great endeavour; in his memoir he wrote of the first volume The first impression was exhausted in a few days; and second and third edition were scarcely adequate to the demand... My book was on every table, and almost on every toilette. He also enjoyed the praise of contemporary historians, such as David Hume. Volumes two and three were published in 1781, and the fourth volume in 1784. It was the perfect project for a scholar of the Enlightenment; Gibbon was a man of his times in his passion for all things Roman and classical, and in that sense he was writing for a willing audience, but would not have been able to carry his readership through six volumes over two decades, had not the journey been worth their effort.

Taking the six volumes as a whole, one can see a uniformity of approach by Gibbon in that he treats the Roman Empire as a single entity, developing the story of its decline as if it had a steady and inevitable progress to the final fall - a decline he broadly attributes to a catastrophic drifting from the classical ideals and writings found in pre-imperial times. Gibbon worked hard to locate and study Latin texts for his work, though there is an imbalance as he had fewer Greek texts to use and was less confident with the language. However, he used at least 8,000 sources from documentary to artefacts, analysing them with great attention to detail. Gibbon takes the reader from the first century AD - The age of Trajan and the Antonines - to the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the story of fourteen centuries described in 71 chapters. His method in crafting the six volumes was to think at great length about what he was to write before committing anything to paper - to suspend the action of the pen until I had given the last polish to my work (although he still laboured through numerous drafts for some of it).

It could be said that Gibbon was courageous in treating the rise of Christianity in the Decline and Fall (chapter 15 in particular) with irony, if not outright scepticism, especially in the light of the furore it caused amongst some more traditionalist commentators; however, despite his own lack of interest in organised religion by this point in his life, he felt he was merely recording the historical phenomena of the times. Despite this, he was compelled to answer his critics in writing, just as those critics had circulated pamphlets to refute Gibbons account of the early Church. One of his detractors, Archdeacon Paley, accused Gibbon of sneering at the Christian faith; as an example of what was so offensive, in chapter fifteen, part one, Gibbon describes the inevitable mix of error and corruption [and] the intolerant zeal of the Christians - characteristics he claimed were derived from the Jewish religion - leaving him open to criticism not only from the Christian Church, but to accusations of anti-Semitism as well. The issue went beyond a desire for historical accuracy, as Gibbon saw the story of the rise of Christianity as crucial to the story of the decline of the Empire, and therefore one that must be told as honestly as possible. He was not an atheist, but neither was he prepared to submit to the standard theology of his day. In this aspect, he demonstrated great integrity, a quality that all historians admire in others and strive for in themselves.

Equally, in listing an obsession with sex and sexual perversions as one of the five reasons the Roman Empire fell, he saw his account of such events as straightforward scholarship and pragmatism. How else, he asked in his memoir, was he to describe the sexual antics of the Empress Theodora, when they had such a strong influence on her husband Justinian and his reign? Gibbon was irritated by this moralistic criticism of his lack of modesty in describing the lifestyle of some Romans. He claimed to have made allowances; he declared that as an historian he had to recount the manner of the times... all English text is chaste, and all licentious passages are left in the obscurity of a learned language (Latin). In his mind, he could do no more.

It would be unfair to outline in detail for the reader the reasons given by Gibbon for the fall of the Roman Empire, but his broad premise, that the empire simply became too unwieldy, lacking in civic virtue and too blind to appreciate the enormity of the barbarian threat, seems to sit uneasily with some modern points of view. Many historians of recent times have applauded the Romans for subtly drawing non-Roman peoples into their influence by offering them responsibility, some local autonomy and a taste of the Roman lifestyle, whereas Gibbon sees this as a surrender to sloppiness and a lack of control; the puny Roman people are contrasted unflatteringly with the tall, muscular and energetic Germanic tribes, to reinforce Gibbons argument that the Romans had allowed themselves to become soft and undisciplined. Modern historians also look to social and economic reasons for the decline of the Empire, which Gibbon does not address in any detail.

Any reader of this publication would do well to also read Gibbons autobiography, which includes valuable insights into the inception and development of the magnum opus . For example, Gibbons undergraduate explorations of faith and the sceptic point of view influenced the first volume of Decline and Fall in its brisk treatment of the rise of Christianity.

Next page