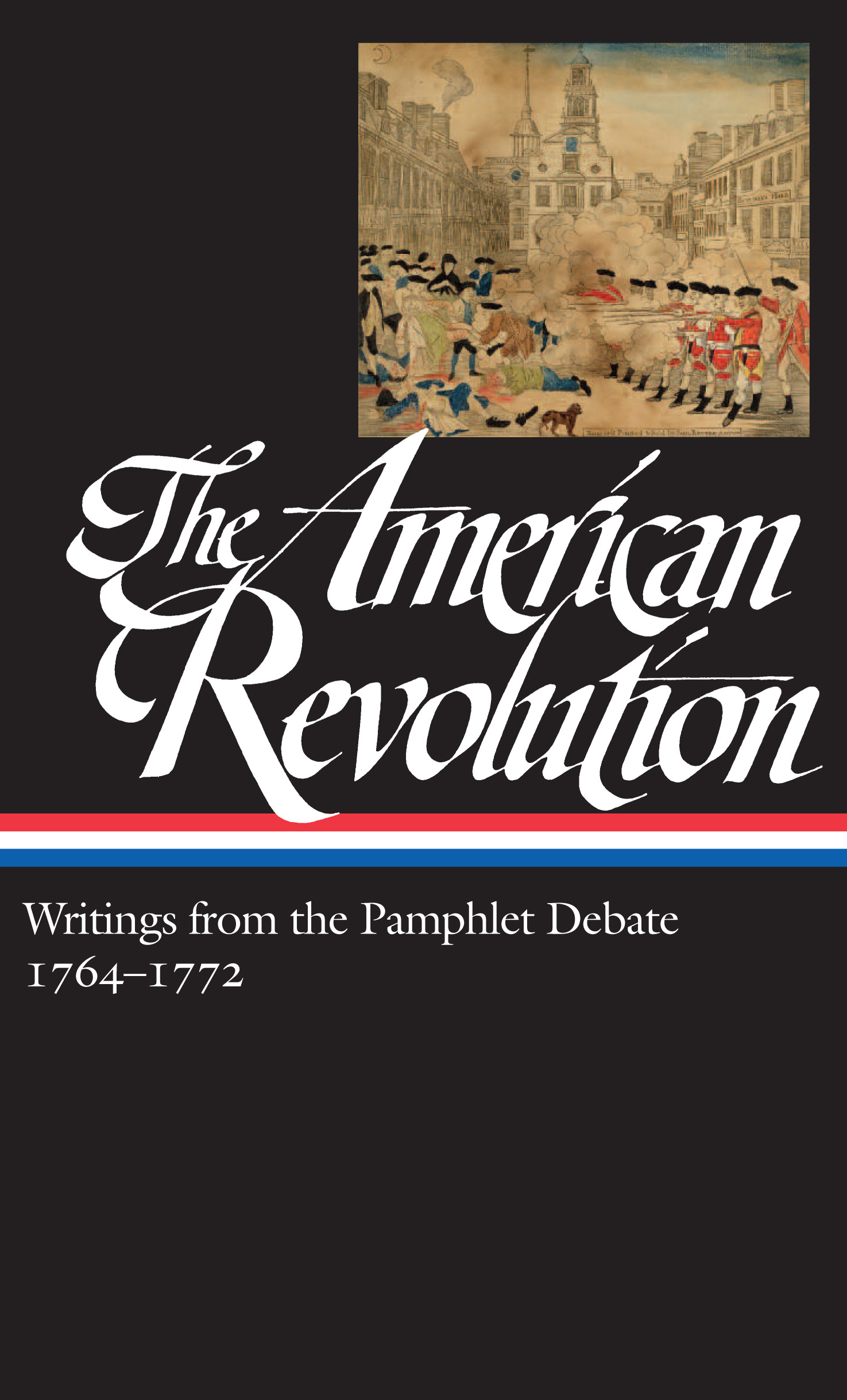

THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

WRITINGS FROM THE PAMPHLET DEBATE

I: 17641772

Gordon S. Wood, editor

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA E-BOOK

Volume compilation, introduction, notes, and chronology 2015 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Visit our website at www.loa.org.

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of Americas best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

Visit our website at www.loa.org to find out more about The Library of America, and to sign up to receive our occasional newsletter with exclusive interviews with Library of America authors and editors, and our popular Story of the Week e-mails.

eISBN 9781598534405

Print ISBN 9781598533774

The American Revolution:

Writings from the Pamphlet Debate 17641772

is kept in print by a gift from

SIDNEY AND RUTH LAPIDUS

to the Guardians of American Letters Fund,

established by The Library of America

to ensure that every volume in the series

will be permanently available.

The American Revolution:

Writings from the Pamphlet Debate 17641772

is published with support from

THE BODMAN FOUNDATION

Preface

What do We Mean by the Revolution? The War? That was no part of the Revolution. It was only an Effect and Consequence of it. The Revolution was in the Minds of the People, and this was effected, from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen Years before a drop of blood was drawn at Lexington. The Records of thirteen Legislatures, the Pamphlets, Newspapers in all the Colonies ought to be consulted, during that Period, to ascertain the Steps by which the public Opinion was enlightened and informed concerning the Authority of Parliament over the Colonies.

John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, 1815

B RITISH imperial reforms undertaken in the 1760s sparked one of the most consequential constitutional debates in Western history. Taken up between American colonists and Britons and among the colonists themselves, this debate was carried on largely in pamphletsinexpensive booklets ranging in length from five thousand to twenty-five thousand words and printed on anywhere from ten to a hundred pages. Easy and cheap to manufacture, these pamphlets were ideal for rapid exchanges of arguments and counter-arguments. Pamphlets concerned with the American controversy from both sides of the Atlantic number well over a thousand, and they cover all of the significant issues of politicsthe nature of power, liberty, representation, rights, constitutions, the division of authority between different spheres of government, and sovereignty. This Library of America volume, the first of a two-volume set, presents the most interesting and important of these works, with a preference in selection for pamphlets directly in dialogue with one another. By the time the debate traced here was over, the first British empire was in tatters, and Americans had not only clarified their understanding of the limits of public power, they had prepared the way for their grand experiment in republican self-government and constitution-making.

Introduction

I N 1763 Great Britain emerged from the Seven Years Waror the French and Indian War, as the American colonists called itas the greatest and richest empire since the fall of Rome. From the Mediterranean to Manila, from Quebec to Havana, its armies and navies had been victorious, so much so that the British public concluded that its military forces were invincible. The Peace of Paris of 1763 compelled France to cede Senegal in West Africa and Dominica, Grenada, Tobago, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in the Caribbean to Britain; renounce all claims to compensation for British naval seizures during the war; destroy its fortifications at Dunkirk; return Minorca and other captured places to Britain; remove its armies from the German states of Hanover, Hesse, and Brunswick; and recognize British suzerainty over India. Most important, the treaty gave Britain undisputed dominance over the eastern half of North America. From the defeated Bourbon powers, France and Spain, Britain acquired huge expanses of territory in the New Worldall of Canada, East and West Florida, and millions of fertile acres between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. At the same time France turned over to Spain New Orleans and the vast territory of Louisiana in compensation for Spains loss of the Floridas. Thus France, the most fearsome of Britains enemies, was entirely removed from the North American continent.

The wars end left many American colonists feeling more British, more proud of their membership in the great Protestant empire, than ever before. They had celebrated the accession of the new king George III in 1760 with more enthusiasm than most of their fellow subjects at home three thousand miles away. And home for many colonists was still Great Britain. Although unprofessional provincial soldiers and sometimes haughty British regulars had often clashed during the war, the overwhelming victory over the Catholic Bourbon powers and, perhaps more important, Prime Minister William Pitts policy of reimbursing the colonists for their financial expenditures, had helped to ease much of the colonists anger at British arrogance. Bostons liberal minister Jonathan Mayhew, who earlier had spoken out passionately against unlimited submission to the higher powers, now exulted in the outcome of the war. He, like many colonists, foresaw the growth of a mighty empire (I do not mean an independent one) in numbers little inferior perhaps to the greatest in Europe, and in felicity to none.

Suddenly, however, the British government was faced with the imposing task of organizing and financing this huge empire, especially the colonies and territories on the North American continent. In the aftermath of the Seven Years War British officials found themselves forced to make long-postponed decisions concerning the North American colonies, decisions that would set in motion a chain of events that ultimately shattered this grand empire and created the United States of America.

The patchwork of territories now known as the first British Empire took shape over the course of the seventeenth century without the benefit of much in the way of central planning. The Crown simply chartered private companies, or granted proprietary rights to individuals, to create colonies that would promote the public interests of the realm. But by the second half of the century the English government began trying to exert tighter control over its colonies, principally through a series of Navigation Acts designed to channel colonial trade and shipping for the benefit of the mother country. The colonists were required to purchase manufactured goods made in Britain, and they were obliged to send to Britain certain enumerated commoditiesexotic staples such as tobacco, rice, furs, and sugarto satisfy its markets before selling them elsewhere. Since commerce remained the dominant business of the empire, its power was felt mainly at the seaports.