Table of Contents

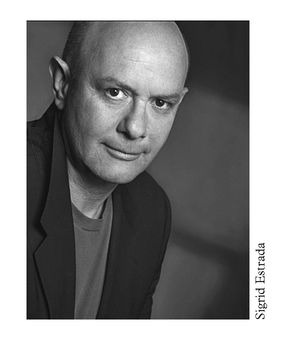

Nick Hornby is the author of the bestselling novels Juliet, Naked, Slam, A Long Way Down, How to Be Good,

High Fidelity, and About a Boy, and the memoir Fever Pitch. He is also the author of Songbook, a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award, Shakespeare Wrote for Money, Housekeeping vs. the Dirt, and The Polysyllabic Spree, and editor of the short story collection Speaking with the Angel. A recipient of the American Academy of Arts and Letters E. M. Forster Award, and the Orange Word International Writers London Award, 2003, Hornby lives in North London.

Also by Nick Hornby

FICTION

HIGH FIDELITY ABOUT A BOY HOW TO BE GOOD

A LONG WAY DOWN SLAM

JULIET, NAKED

NONFICTION

FEVER PITCH

SONGBOOK

THE POLYSYLLABIC SPREE HOUSEKEEPING VS. THE DIRT SHAKESPEARE WROTE FOR MONEY

ANTHOLOGY

SPEAKING WITH THE ANGEL

INTRODUCTION

The First Draft

I knew the moment Id finished Lynn Barbers wonderful autobiographical essay in Granta, about her affair with a shady older man at the beginning of the 1960s, that it had all the ingredients for a film. There were memorable characters, a vivid sense of time and place - an England right on the cusp of profound change - an unusual mix of high comedy and deep sadness, and interesting, fresh things to say about class, ambition and the relationship between children and parents. My wife, Amanda, is an independent film producer, so I made her read it, too, and she and her colleague Finola Dwyer went off to option it. It was only when they began to talk about possible writers for the project that I began to want to do it myself - a desire which took me by surprise, and which wasnt entirely welcome. Like just about every novelist I know, I have a complicated, usually unsatisfactory relationship with film writing: ever since my first book, Fever Pitch, was published, I have had some kind of script on the go. I adapted Fever Pitch for the screen myself, and the film was eventually made. But since then there have been at least three other projects - a couple of originals, and an adaptation of somebody elses work - which ended in failure, or at least in no end product, which is the same thing.

The chief problem with scriptwriting is that, most of the time, it seems utterly pointless, especially when compared with the relatively straightforward business of book publishing: the odds against a film, any film, ever being made are simply too great. Once you have established yourself as a novelist, then people seem quite amenable to the idea of publishing your books: your editor will make suggestions as to how they can be improved, of course, but the general idea is that, sooner or later, they will be in a bookshop, available for purchase. Film, however, doesnt work that way, not least because even the lower-budget films often cost millions of pounds to make, and as a consequence there is no screenwriter alive, however established in the profession, who writes in the secure knowledge that his work will be filmed. Plenty of people make a decent living from writing screenplays, but thats not quite the same thing: as a rule of thumb, Id estimate that there is a 10 per cent chance of any movie actually being put into production, especially if one is working outside the studio system, as every writer in Britain does and must. I know, through my relationship with Amanda and Finola and other friends who work in the business, that London is awash with optioned books, unmade scripts, treatments awaiting development money that will never arrive.

So why bother? Why spend three, four, five years rewriting and rewriting a script that is unlikely ever to become a film? For me, the first reason to walk back into this world of pain, rejection and disappointment was the desire to collaborate: I spend much of my working day on my own, and Im not naturally unsociable. Signing up for An Education initially gave me the chance to sit in a room with Amanda and Finola and Lynn and talk about the project as if it might actually happen one day, and later on I had similar conversations with directors and actors and the people from BBC Films. A novelists life is devoid of meetings, and yet people with proper jobs get to go to them all the time. I suspect that part of the appeal of film for me is not only the opportunity for collaboration it provides, but the illusion it gives of real work, with colleagues and appointments and coffee cups with saucers and biscuits that I havent bought myself. And theres one more big attraction: if it does come off, then its proper fun, lively and glamorous and exciting in a way that poor old books can never be, however hard they try. Even before this films release, we have taken it to the Sundance Festival in Utah, and Berlin. And I have befriended several of the cast, who, by definition, are better-looking than the rest of us... What has literature got, by comparison?

I wrote the first draft of An Education on spec, sometime in 2004, and while doing so, I began to see some of the problems that would have to be solved if the original essay were ever to make it to the screen. There were no problems with the essay itself, of course, which did everything a piece of memoir should do; but by its very nature, memoir presents a challenge, consisting as it does of an adult mustering all the wisdom he or she can manage to look back at an earlier time in life. Almost all of us become wiser as we get older, so we can see pattern and meaning in an episode of autobiography - pattern and meaning that we would not have been able to see at the time. Memoirists know it all, but the people they are writing about know next to nothing.

We become other things, too, as well as wise: more articulate, more cynical, less nave, more or less forgiving, depending on how things have turned out for us. The Lynn Barber who wrote the memoir - a celebrated journalist, known for her perspicacious, funny, occasionally devastating profiles of celebrities - shouldnt be audible in the voice of the central character in our film, not least because, as Lynn says in her essay, it was the very experiences that she was describing that formed the woman we know. In other words, there was no Lynn Barber until she had received the eponymous education. Oh, this sounds obvious to the point of banality: a sixteen-year-old girl should sound different from her sixty-year-old self. What is less obvious, perhaps, is the way the sixty-year-old self seeps into every brush-stroke of the self-portrait in a memoir. Sometimes even the dialogue that Lynn provided for her younger version - perfectly plausible on the page - sounded too hard-bitten, when I thought about a living, breathing young actress saying the words. I had been here before, in a way, with the adaptation of Fever Pitch. In a memoir, one tries to be as smart as one can about ones younger self - thats sort of what the genre is, and thats what Lynn had done. In a screenplay, however, one has to deny the subject that insight, otherwise theres no drama, just a character understanding herself and avoiding mistakes.