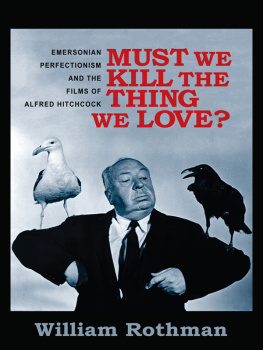

Must We Kill the Thing We Love?

FILM AND CULTURE

John Belton, Editor

FILM AND CULTURE

A series of Columbia University Press

Edited by John Belton

For the list of titles in this series, see .

MUST WE

KILL THE

THING

WE LOVE?

Emersonian Perfectionism and the Films of Alfred Hitchcock

William Rothman

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press New YorkColumbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53730-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rothman, William.

Must we kill the thing we love? : Emersonian perfectionism and the films of Alfred Hitchcock / William Rothman.

pages cm (Film and culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16602-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-16603-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-53730-8 (ebook)

1. Hitchcock, Alfred, 18991980Criticism and interpretation. 2. Redemption in motion pictures. 3. Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 18031882Influence. I. Title.

PN1998.3.H58R683 2014

791.430233092dc23

2013038575

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

COVER PHOTO: AF archive / Alamy

COVER DESIGN: Milenda Nanok Lee

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

For Stanley Cavell

Contents

I wrote HitchcockThe Murderous Gaze more than thirty years ago. During that time I was teaching at Harvard and in almost daily conversation with Stanley Cavell, who was completing Pursuits of Happiness, his seminal study of the Hollywood genre he calls the comedy of remarriage (It Happened One Night [Frank Capra, 1934], The Awful Truth [Leo McCarey, 1937], Bringing Up Baby [Howard Hawks, 1938], His Girl Friday [Howard Hawks, 1940], The Philadelphia Story [George Cukor, 1940], The Lady Eve [Preston Sturges, 1941), Adams Rib [George Cukor, 1948]).

Although The Murderous Gaze approaches Hitchcocks films primarily through the prism of authorship, it notes that the Hitchcock thriller can also be viewed as a genre, or perhaps a cluster of closely related genres, comparable to the comedy of remarriage or the melodrama of the unknown woman. As Cavells own essay on North by Northwest demonstrates, Hitchcock thrillers share the concerns of the genres he studied. And there are differences that can be charted. In the Hitchcock thrillers that revolve around a girl-at-the-threshold-of-womanhood, for example, the narrative charts the stages of a womans education, just as in remarriage comedies. And that education goes hand in glove with the development of a romantic relationship.

In comedies of remarriage a woman and a man pursue happiness not by overcoming societal obstacles to their marriage, as in classical comedies, but by overcoming obstacles internal to their relationship, obstacles that are between and within themselves, obstacles they cannot overcome without achieving a radically changed perspective. These Hollywood movies present women and men as equals, as having an equal right to pursue happiness and as being equal spiritually or, we might say, morallyequal in their powers of imagination and thinking and in their capacity to cultivate the better angels of their nature. What is at issue in such films is not simply whether the leading woman and man will marry, or remarry, but whether the kind of marriage they create together will be a relationship worth having, one that enables them, as individuals and as a couple, to embrace every day and every night in a spirit of adventurea kind of marriage exemplified by Nick and Nora (William Powell and Myrna Loy) in The Thin Man (W. S. Van Dyke, 1934), another landmark film made the same year as It Happened One Night, the earliest of the films Pursuits of Happiness scrutinizes. Hence comedies of remarriage pose, and address, a philosophical question about marriage itself. What is marriage? What, if anything, validates or legitimates a marriage, if a couple can be married according to the church and the laws of the state and yet, by the higher standards of the comedy of remarriage, not have a true marriage?

The Philadelphia Story renders explicit that this question about marriage is also a question about what it is to be human, a question about human relationships in general, a question about community and, as such, a question for, and about, America. Implicitly advocating Americas joining the war against fascism already raging in Europe at the time of its release, The Philadelphia Story is a summary statement as to what makes America worth fighting for, what is worth preserving in its heritage. In the comedy of remarriage a woman and man seek, and achieve, a conversation of equalsa relationship with each other, at once private and public, based on mutual trustthat can serve as a model of community and thus as an inspiration for America in its own quest to form a more perfect union.

What is worth fighting for, The Philadelphia Story declares, is not America as it is (as the wartime documentary series Why We Fight was later to assert, whitewashing reality in a way Hollywood romantic comedies of the 1930s refrained from doing). America as it is, The Philadelphia Story asserts (as do all the romantic comedies Cavell studies), is a place where the likes of George Kittredgethe phony man of the people trumpeted by cynical Sidney Kidds media empirepasses for a great American. Americas promise has not yet been fully realized. America has not yet become America. And yet, these romantic comedies affirm, this unattained America, as Ralph Waldo Emerson calls it, is still attainable. The dream of a more perfect union was still alive in 1930s America, though imperiled, as it was in Emersons time, when, as he wrote, the moral scourge of slavery was keeping America from taking a step toward becoming America. (The dream is still alive todayand still in peril.)

The remarriage comedies Cavell celebrates are grand entertainments that gave pleasure to viewers living through dark times, but they also entered into a serious conversation with their culture that set a high standard of moral purpose. Their commitment to channeling the awesome power of film to help America and Americans to awaken, to change, was not confined to a single genre, a point Cavell fleshes out in

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press New York