All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Published simultaneously in the United States of America by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company

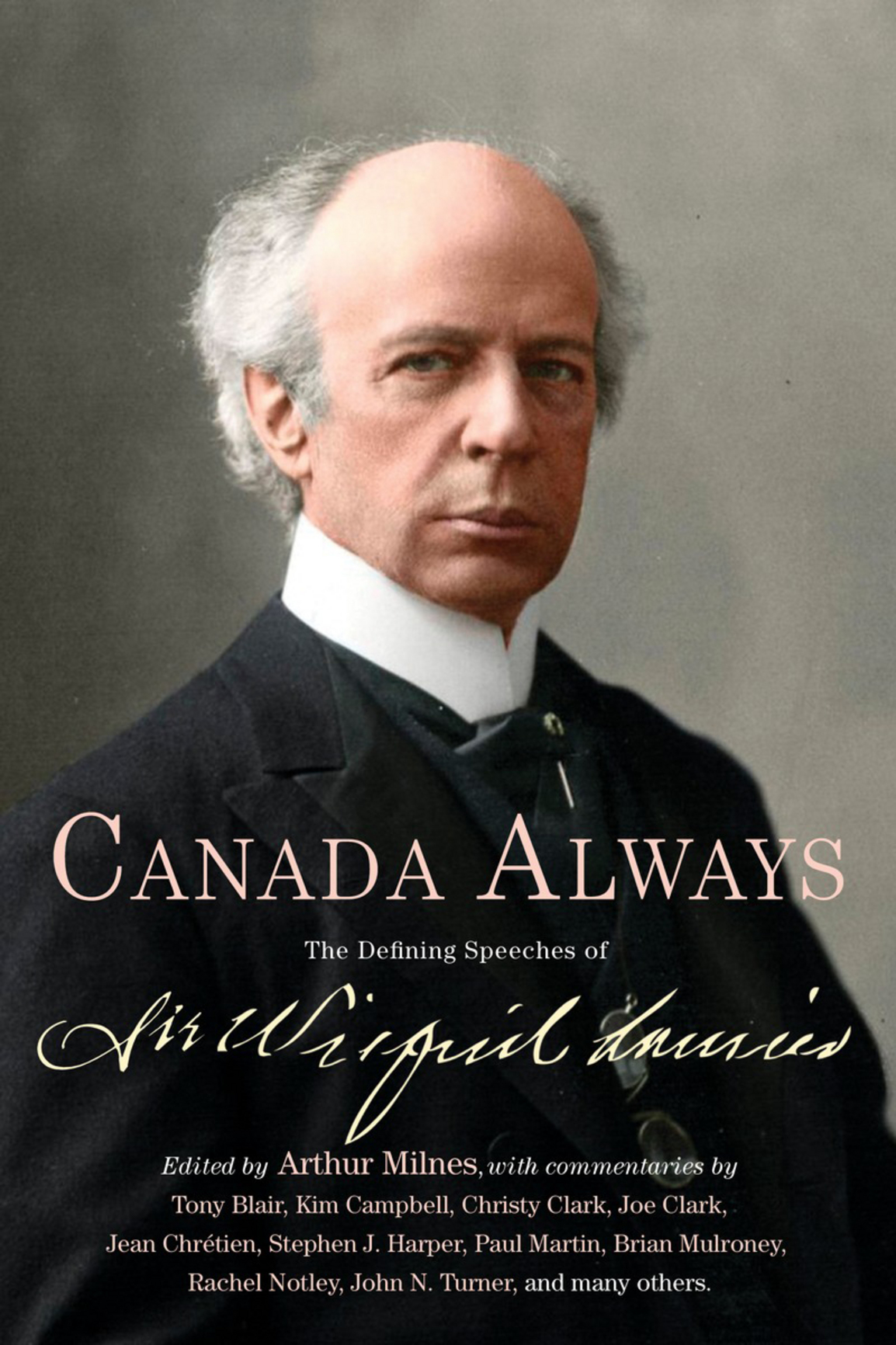

Cover: Colour by Mark Truelove/Canadian Colour; Photograph by William J. Topley/Patent and Copyright Office, Library and Archives Canada

For my part, when the hour for final rest shall strike, and when my eyes shall close forever, I shall consider that my life has not been altogether wasted, if I shall have contributed to heal one patriotic wound in the heart even of a single one of my fellow countrymen and to have thus promoted, even to the smallest extent, the cause of concord and harmony between the citizens of the Dominion.

INTRODUCTION

SIR WILFRID LAURIER: A RULER OF MEN

BY ARTHUR MILNES

As Canadians enter the 175th anniversary year of the birth of their first French-Canadian prime minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, it is an opportune moment to re-acquaint ourselves with his public words and story.

In his famous eulogy of Sir John A. Macdonald, Laurier said the Father of Confederations life was the history of Canada. As Canada cemented its place in the post-Macdonald era, few would disagree that Lauriers life, too, became in so many ways the history of Canada. That is why his public words, even today, remain so crucial to understanding our nation.

Writing during Lauriers lifetime, journalist John Willison captured these thoughts:

There is more of the history of Canada in Sir Wilfrid Lauriers speeches than in those of any other public man of his generation, and his remarkable historical equipment lends steadiness and sobriety to his.

Laurier, born on November 20, 1841, devoted almost his entire adult life to the business of politics. First elected to the House of Commons in 1874, he was still an MP when he died in 1919. By that time he had served as a cabinet minister under Alexander Mackenzie, and had risen to become leader of the Liberal Party and leader of the Opposition, prime minister from 1896 until 1911, and then leader of the Opposition once again.

It was a remarkable journey, one that can be followed today in his wealth of public addresses, delivered both in the Commons and on platforms across Canada.

Alberta and Saskatchewan joined Confederation, national railways were built, and Laurier followed in Macdonalds footsteps by encouraging, more successfully, immigration to the West from Europe.

In Laurier, Canadians also had for the first time a prime minister widely celebrated on the world stage. Many of the addresses in this collection are drawn not only from Canadian newspapers, but from those in Australia, across the United States, and in Europe.

Lauriers life and career is a story of confidence, national optimism and success. But it is also one of a Canadian leader continually buffeted by racial and religious intolerance from French and English, Protestant and Catholic. His career culminates in the brutal realities of the 1917 conscription campaign.

At the train station in what is now Thunder Bay, Ontario, in December 1917, Laurier receives the evening telegrams reporting on the election results. It is dark. The former prime minister of Canada has just turned seventy-six. As he walks along the station platform, a small group of friends gather around him protectively. He is defeated and will never face Canadians at the polls again. His white plume no longer led to victory.

A reporter, whose name has been lost to history, described the scene:

The tall figure of the Liberal chieftain was surrounded by his special party as he scanned the figures that meant so much to him. He stood hatless as he absorbed the details of his defeat, and if his emotions were not well under control his closely surrounding friends sheltered any display he made from the crowd on the platform outside.

One wonders what would have become of Canada had Laurier given up and returned to his native Quebec and his nationalist roots. Had that happened, I submit, there would be no Canada as we know it today: both in office as prime minister or in Opposition, he was that significant.

In his lifetime Laurier was well aware of the leading place he had already earned in Canadian history.

In 1916 an artist painted a portrait of Laurier to hang in the Legislative halls of Quebec, where the sound of his magic voice had first been heard in parliamentary speech, it is recorded. The artist began to paint the Laurier of the sunny ways. The old man corrected him. No, if you please, he said gravely, paint me as a ruler of men. It was the Cardinal speaking; the man who had disciplined more Cabinet politicians than even Macdonald, the master of Cabinets; the old man who remembered the power of an earlier day.

Still, that Northern Ontario train station in 1917 was a long way and years removed from the days when Laurier had electrified friend and foe alike with his brave defence of Louis Riel, had taken the Queens Diamond Jubilee celebrations of 1897 by storm, and modernized Canadian politics by holding the first-ever post-Confederation party convention on the road to power.

In his collected speeches is found the entire story. For Canadians of today, including those who have lulled themselves into thinking that the pull of Quebec separation is gone forever, Lauriers words should be required reading. His speeches remind us that Canada requires vision, constant care, concern mixed with optimism, and more than a little luck. Lauriers lifes work will therefore be important to recall as we prepare to mark our nations 150th anniversary in 2017.