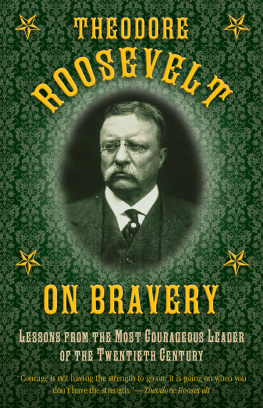

Waller R. Newell

It is character that counts in a nation as in a man. It is a good thing to have a keen, fine intellectual development in a nation, to produce orators, artists, successful business men; but it is an infinitely greater thing to have those solid qualities which we group together under the name of charactersobriety, steadfastness, the sense of obligation toward ones neighbor and ones God, hard common sense, and, combined with it, the lift of generous enthusiasm toward whatever is right. These are the qualities which go to make up true national greatness.

Once again it is my pleasure to thank Judith Regan for her continuing strong support for this book and her keen interest in the debates and issues that inform it. I am also grateful to my editor, Cal Morgan, for his usual impeccable edit and sound instincts about the shape of the manuscript.

Special thanks are due to the Earhart Foundation for its generous support during the period in which I researched and wrote this book. I should also mention that an earlier version of the introduction was delivered as a public lecture for the John M. Olin Programme on Politics, Morality, and Citizenship at the Institute of United States Studies, the University of London. I would like to thank the Institute and its director, Gary McDowell, for the invitation to speak and for their hospitality during my stay in London.

As usual, many friends and colleagues have rendered good advice, useful tips, and practical assistance. Thanks are due in particular to my agent, Chris Calhoun, of Sterling Lord Literistic. My student research assistants, Geoffrey Kellow, Matthew Post, and Stephen Turpin, also provided some very useful help.

In this as in all things, my wife, Jacqueline Etherington Newell, was my chief partner, providing generous amounts of insight, needed criticism, and inspiration.

I would like to dedicate this book to the memory of my brother, Richard Newell, and my uncle George Newell, both of whom passed away while I was writing it.

This is a book about how to be a man. I ask the reader to join me on a search for the manly heart. There are five stages on that journey, corresponding to the five main ingredients of a satisfying lifelove, courage, pride, family, and country. The correct balance of these five virtues, I will try to show, is the secret of happiness for a mana life that is emotionally, erotically, and spiritually satisfying.

But do we really need to be reminded of how to be a man? After all, the heroic response to the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, proved that manliness still exists in abundant supply. Americans may not talk much about manliness, but they know how to show it. At the same time, however, the recovery of manliness in response to the calamity may have been a close call. In the aftermath, many wondered: Were we somehow vulnerable to the attack? By this they meant not merely vulnerable in terms of military might or security measures, all of which were speedily addressed, but a more troubling possibility: Were we spiritually vulnerable? Had the world grown to believe that Americans were corrupt, lazy, self-indulgent, and hedonistic, lacking conviction in our way of life and unwilling to defend it? This dialogue will go on for a long time, and the meaning of manly virtue is central to it.

Many said that 9/11 had brought the Age of Irony to an end. No more frivolity, easygoing relativism, or flippant disdain for the old-fashioned virtues. In many ways, 9/11 was a moral wake-up call, reminding us that, after thirty years of debunking the traditional virtues, we are as much in need of them as ever, and perhaps did not do enough to convince the enemies of democracy that we still know what those virtues are and how to act on them. War is never desirable, and there is no silver lining to the slaughter of innocents. Still, the history of all civilizations and countries shows that war can spark a period of soul-searching, stocktaking, and moral regeneration, spanning all subcultures and reminding us of our shared responsibilities as citizens. President Bush has wondered aloud whether Americans spend a little bit too much time playing video games and enjoying their other toys, and not quite enough time giving of themselves for others. These reflections are common to all shades of the political spectrum, and they in no way amount to blaming the victim. It is a natural response to human suffering to wonder if we can avoid calamities of the same kind in the future by heeding the call to improve ourselves, individually and as a nation. If we dont ask ourselves such painful questions, then the innocent victims will have died in vain. If something good can come of the tragedy, helping us avoid a repetition of it, then their deaths will be more greatly hallowed than if we had simply returned to our usual routines.

This has happened many times before, and it will doubtless happen again. In his novel Nana, Emile Zola chronicled the moral disintegration of Paris into an endless playhouse of jaded pleasure seeking. The book portends the devastating defeat of France in 1871 by the armies of Bismarcks Prussia, to be delivered like the judgment of God on Sodom and Gomorrah. Closer to our own era, the movie Casablanca summed up the feeling produced in many by the rise of Nazi Germanythat it was time to put aside the nightclub-hopping cynicism of the Lost Generation and join the battle for good against evil. The further we go back in time, the more often we encounter such reflections on the value of war as a moral wake-up call. One of the original versions is St. Augustines City of God . He used the sack of Rome by Alaric the Goth in A.D. 410 to raise the same questions: Did the Roman Empire invite aggression because its ancient civic and military virtues were played out as a result of an underlying spiritual exhaustion?

The response of Americans to 9/11 was a triumph. But, far from proving that we dont need to reflect on the meaning of manliness, it only shows how urgently this debate must be carried on and deepened. The Age of Irony did not happen overnight, and however sobered we may have been by the terrorists devastating attack, its effects wont disappear overnight. They are still with us. The events of 9/11 can be a blessing in disguise if the valor they brought forth inspires us to recover the wellsprings of manly virtue, not only in the heat of action but through longer-lasting reflection. Its the greatest conceivable testament to America that, when faced with an unspeakable cataclysm, it can reach deep down into the moral fiber built up through centuries of challenge. But during the intervals of peace, when we have time to reflect, we need to nourish that moral fiber with patient and thoughtful self-examination. Americans proved their manliness on 9/11 with deeds. Now we need to recover the words, because in the long run of a nations life, it is the words that inspire and shape the deeds.

There is a beautiful image, originating in Hindu thought and repeated by the ancient philosopher Plato, that compares the human soul to a celestial chariot riding through the heavens. For me, this image best sums up the five paths to manliness I mentioned at the beginninglove, courage, pride, family, and countryand how they relate to one another in an integrated and satisfying life. According to this ancient image, the charioteer stands for the human mind. The horses stand for the two most powerful of human passions, love and valor. The proper ordering of a mans soul requires that the passions of love and valor always be guided by the dictates of reason. If the horses are not sufficiently reined in by the charioteer, if they are allowed their own way, these powerful steeds will pull the celestial chariot out of its heavenly arc, plunging it into a lower world of chaotic lust and violence. If, however, the charioteer is firmly in control of his steeds, the chariot of the soul will continue to soar upward to the celestial heights of eternal happiness, fulfillment, and honor.