The Real Thing

1989 The University of North Carolina Press

Preface to the Twenty-fifth Anniversary Edition

2014 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the original edition of this book as follows:

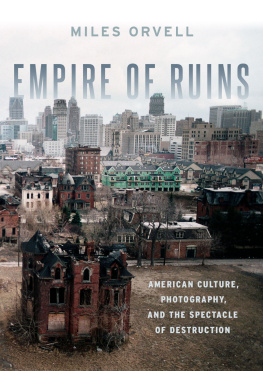

Orvell, Miles.

The real thing: imitation and authenticity in American

Culture, 1880-1940 / Miles Orvell

p. cm.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. United StatesCivilization1865-1918. 2. United StatesCivilization1918-1945. 3. United StatesIntellectual life, 1865-1918. 4. United StatesIntellectual life20th century. 5. Material cultureUnited States. 6. American literatureHistory and criticism. 7. PhotographyUnited StatesHistory. 8. Imitation. 9. Authenticity (Philosophy). I. Title

E169.1.0783 1989 88-20886

973de19 CIP

ISBN 978-1-4696-1536-3 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-1537-0 (ebook)

The author is grateful for permission to reproduce the following: From Collected Early Poems by William Carlos Williams. Copyright 1938 by New Directions Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation.

From Paterson by William Carlos Williams. Copyright 1946, 1948, 1949, 1951, 1958. Copyright 1963 by Florence H. Williams. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation.

From Imaginations by William Carlos Williams. Copyright 1970 by Florence H. Williams. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation.

A substantial portion of Chapter 1 first appeared as Reproducing Walt Whitman: The Camera, the Omnibus and Leaves of Grass, in Prospects 12 (1987) and is reprinted by permission of Cambridge University Press.

An earlier version of Chapter 3 was awarded a Reva and David Logan Grant in Support of New Writing on Photography and appeared as Almost Nature: The Typology of Late Nineteenth Century American Photography, in Views: Supplement (Fall 1986). It is reprinted in revised form by permission of the Photographic Resource Center in Boston and the Logan Grants.

18 17 16 15 14 5 4 3 2 1

THIS BOOK WAS DIGITALLY PRINTED.

To Gabriella

Contents

PART ONE

The Condition of Future Development

PART TWO

A Culture of Imitation

PART THREE

Inventing Authenticity

Preface to the Twenty-fifth Anniversary Edition

Twenty-five years after the publication of The Real Thing, any consideration of what a real thing is must now take place within a changed environment, thanks in large part to the invention of the World Wide Web, launched about a year after the books publication. Surely the virtual culture of the twenty-first century, based on the digital universe we have come to inhabit, has changed the way we think about reality in many ways. But things do not change all of a sudden or completely, and any period, including our own, is layered with past materials and conceptual frames that continue to influence the future. The tension between imitation and authenticity that was central to the narrative in The Real Thing, remains, I would argue, a dominant framework for understanding American culture, however transfigured our culture has become by virtual reality.

The terms I use in the subtitleimitation and authenticityhave in fact only gained in currency in the years since the books original publication, with some 1,500 titles that contain one of the words or both appearing in the Library of Congress catalogue, encompassing titles in philosophy, religion, literature, education, and psychology. (In the twenty-five years preceding its publication only 250 titles used those words.) The exponential growth of these terms in intellectual discourse suggests their increasing relevance as compass points in a culture in which copies of everything have proliferated and in which that elusive quality of authenticitythe genuine, the sincere, the realhas taken on a correspondingly significant new meaning.

The chief contribution of The Real Thing was to identify the opposition between these two cultural modelsimitation and authenticityas one that marks the shift from the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century and remains an essential and defining element in American culture.of twenty-five years, I can see it as almost an exemplary if not inevitable production of its own cultural moment, and I want to use this opportunity to explain a little how it evolved. I also want to test its relevance as a lens through which to view our twenty-first-century culture of virtual reality. And finally, I want to look briefly beyond its boundaries and point to some of the ways that other scholars have extended the core concepts beyond my own imagination at that moment.

My interest in authenticity emerged in the 1960s, though I did not recognize it as such at the time. I remember coming across a mass paperback edition of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men that Ballantine Books brought out in 1966, while I was in graduate school, twenty-five years after that books own first edition. Michael Harringtons The Other America had come out in 1962, revealing a world of poverty that had been airbrushed out of American reality in the 1950s, and James Agees text, along with Walker Evanss photographs, seemed both archaic and still relevant in this post-Harrington moment. Agees narrative, meditating on conditions of poverty in the South, was intriguing (and also baffling) in its exploration of the very grounds of representation; and so were Evanss photographs, with their deceptively transparent rendering of surfaces and forms. The books republication in the 1960s was part of the growing fascination at that time with fact, with documentary, and with a broader revival of interest (among academics at least) in 1930s leftist culture that was emerging as a complement to the New Left of the 1960s. Documentary represented as well an effort to get closer to reality in a culture that seemed at times to be going in the opposite direction in its willing submission to the domination of the television image and in its fantastic and lethal pursuit of Communism in Vietnam.

Of course the documentaries being produced in the 1960s and 1970s were far different from documentary in the 1930s, and the form was being reinvented as a self-conscious hybrid of fact and fiction. Norman Mailer was one of its reinventors, and reporting on his participation in the March on the Pentagon, he constructed a two-part narrative, Armies of the Night (1968), that exploited the twin resources of history and the imagination, creating a synthesis of fiction and actuality in its two parts, History as a Novel and The Novel as History. Tom Wolfes widely imitated new journalism was another powerful sign of this compulsion to get closer to the real thing, with its encyclopedic mimesis of popular culture, portrayed in the rhetorical excess of Wolfes comic invention. And the television docudramagrowing in popularity after the spectacular success of the TV miniseries Roots in 1977was yet another form of this fusion of fact and fiction, a genre that packaged the content of reality in the costume and colors of fiction. (Roots was even more fused, or confused, than it purported to be, since creator Alex Haley later admitted to inventing the particular line of African descent he had claimed; also, he had plagiarized parts of the novel Roots, on which the series was based.)