The Sixth Sense of the Avant-Garde

CONTENTS

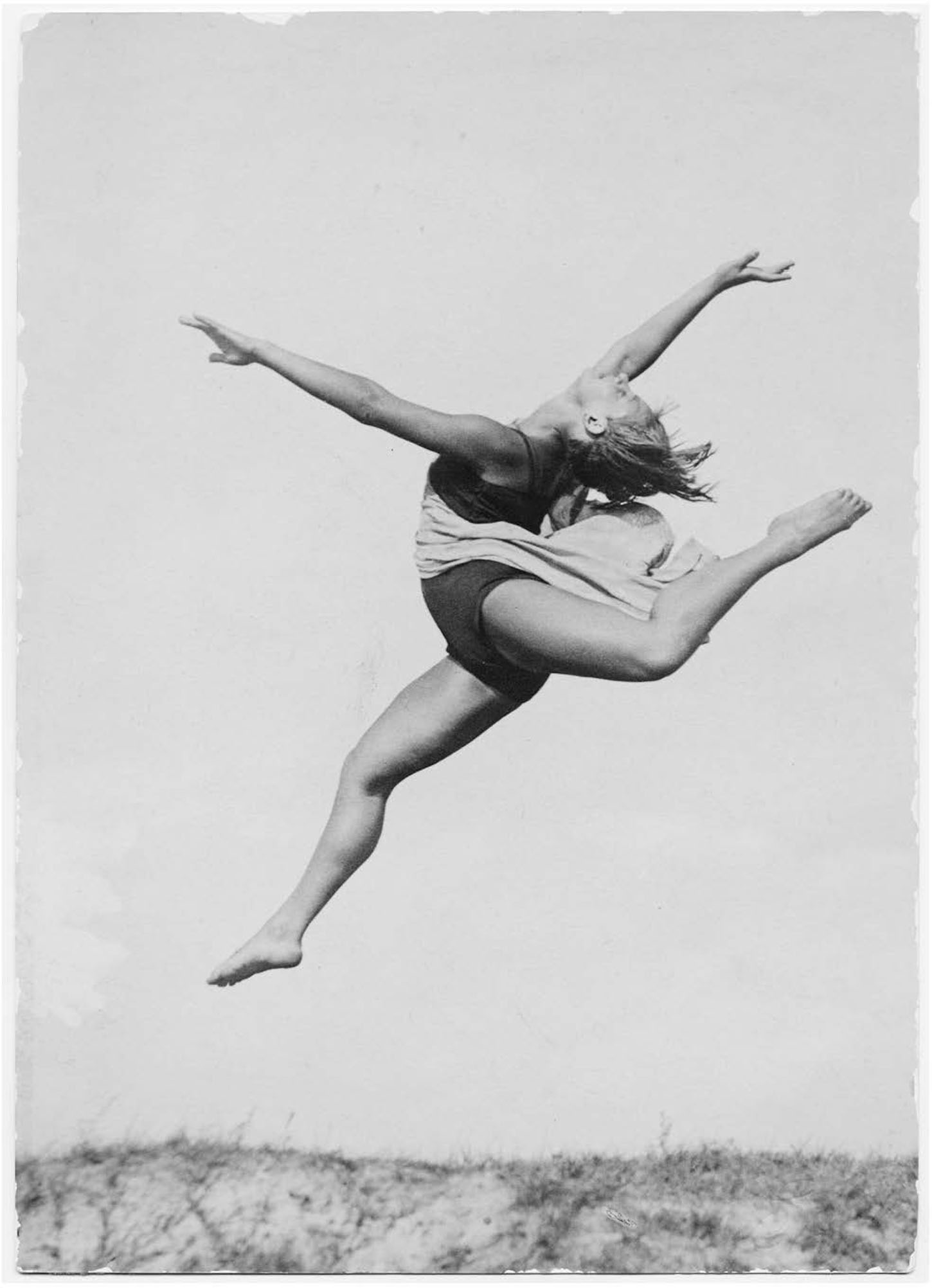

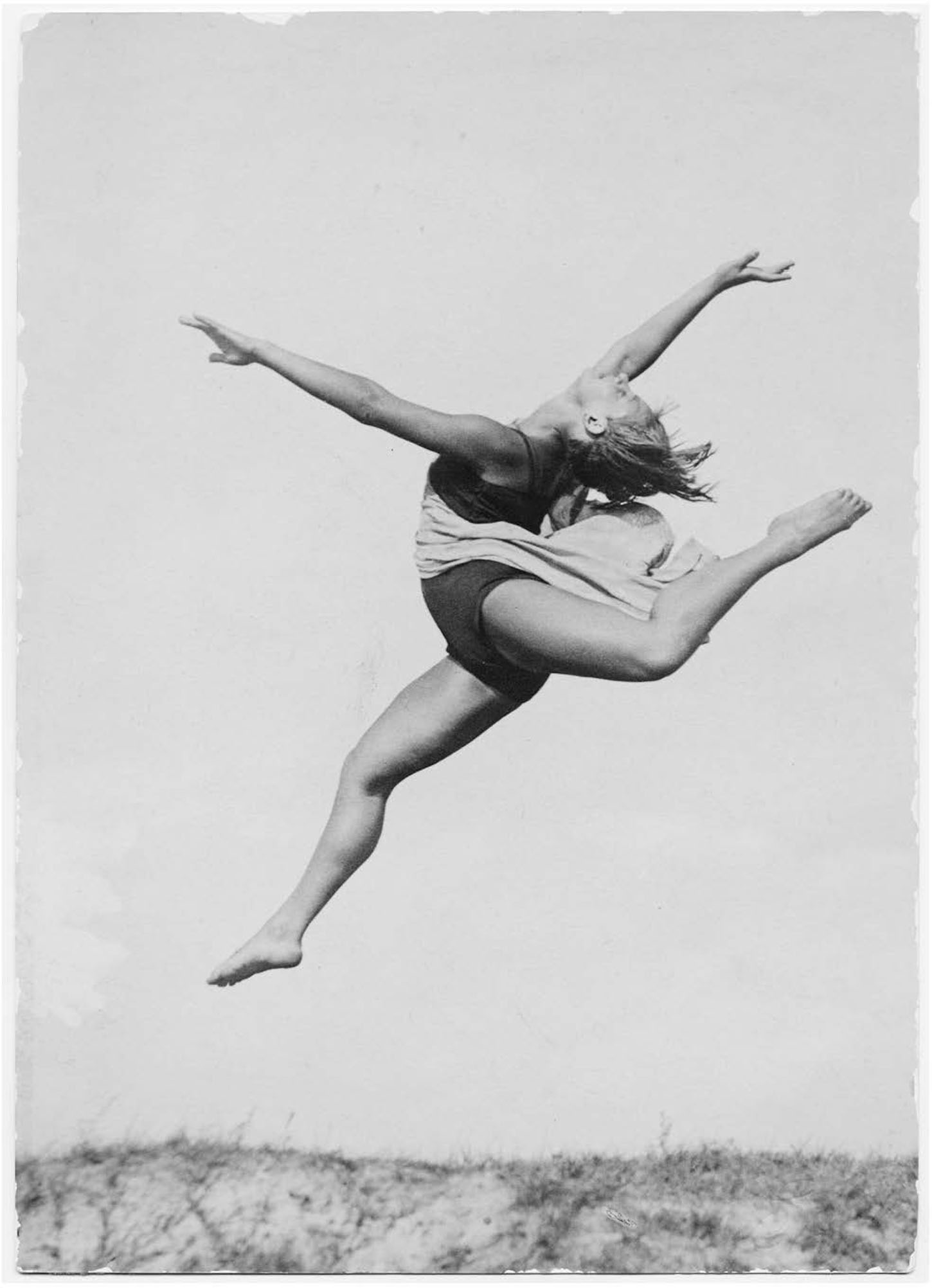

Vera Mayas Studio. Photo: S. Rybin, 1927. Courtesy A. A. Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum, Moscow.

Heptachor Studio in the 1920s. Courtesy Tatiana Trifonova.

Stefanida Rudneva. The Wings, mid-1920s. Courtesy Tatiana Trifonova.

Stefanida Rudneva and Natalia Pedkova. A study to Dance of the Skomorokhi by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, mid-1920s. Courtesy Tatiana Trifonova.

Fedor Golovin. M. F. Kokoshkina, Andrei Bely and F. F. Kokoshkin. Paper, Indian ink. 1917. Courtesy Andrei Bely Memorial Apartment on Arbat, Moscow.

Vasily Kamensky. Tango with Cows. Ferro-concrete Poems. 1914.

An Embarrassing Situation. Amongst bare-footed dancers there is a new trend to illustrate poetry with dances. Courtesy Andrei Rossomakhin.

Vladimir Mayakovsky (1924).

Nikolai Foregger. Machine Dances (1923). From Ritm i kultura tantsa (Rhythm and the Culture of Dance) (Moscow and Leningrad, 1926).

Cyclography of stroke movement. Central Institute of Labour, Moscow, 1920s. From R. Flp-Miller, The Mind and Face of Bolshevism (London and New York, 1927).

Nikolai Bernshtein in the Central Institute of Labour. Moscow, mid-1920s. From R. Flp-Miller, The Mind and Face of Bolshevism (London and New York, 1927).

This book is a fully rewritten and expanded version of Irina Sirotkina, Shestoe chuvstvo avangarda: tanets, dvizhenie, kinesteziia v zhizni poetov i khudozhnikov (The Sixth Sense of the Avant-garde: Dance, Movement, Kinaesthesia in the Lives of Poets and Artists), published in the series Avant-garde, copyright the European University Press in Saint-Petersburg (EUSP), Russian Federation, in 2014, republished in a new edition in 2016. This English-language version is published by arrangement with EUSP, whose involvement is gratefully acknowledged. We sincerely thank the editor of the Russian text, Andrei Rossomakhin, for his deep interest and support.

The book owes much to a wide range of scholars and Russian institutions. It crosses borders between Slavic studies, dance and performance studies, history of art and literature, cultural history and history of science in order to draw on the riches of research in the humanities. The notes indicate our debts. Amidst all the scholarship on the Russian avant-garde, it is hard to overemphasize the contribution by a scholarly couple, John E. Bowlt and Nicoletta Misler. In addition to their own prolific writings and curatorship of exhibitions, they edit Experiment: A Journal of Russian Culture, twenty-one volumes (1995 to present) including academic inquiries into ballet, ballroom dance, theatre, gymnastics and body culture in early twentieth-century Russia. They have generously contributed their enthusiasm and knowledge to our project.

We also would like to thank Caryl Emerson, Lynn Garofola and Dee Reynolds for their encouraging interest in and support for the book.

The English text, based on a translation from Irina Sirotkina, Shestoe chuvstvo, is our own. We thank Sergei Zhozhikashvili for many explanations of the Russian language and much patience with his student, Roger Smith.

We are happily indebted to our experience of the Russian tradition of musical movement, to our teachers Aida Ailamazian and Tatiana Trifonova, and to all those with whom we have shared movement.

We acknowledge the following permissions:

Extract in chapter 2, from Rainer Maria Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus, trans. J. B. Leishman (1936), reprinted by permission of the Random House Group Ltd.

The epigram to chapter 6, Vladimir Mayakovsky, author, and George Hyde, translator, from How Are Verses Made?, Bristol Classical Press, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

The epigram to chapter 7, from Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, trans. R. J. Hollingdale, copyright R. J. Hollingdale, 1961, 1969, reprinted by permission of Penguin Random House UK.

All translations are our own, unless otherwise acknowledged. We transliterate Russian names and words according to a modified US Library of Congress standard; where more familiar versions of names are in common use (e.g. Dostoevsky), we adopt that form. Where we cite sources, we copy names as they appear in that source.

Where ellipses () appear in quotations, they are our insertions, unless noted as being in the original text.

Where emphases are added to quotations, this is noted.

| GAKhN | Academy of Art Sciences (All-Russian, and after 1926, State) |

| GARF | State Archive of the Russian Federation |

| GINKhUK | State Institute of Art Culture (Petrograd) |

| INKhUK | Institute of Art Culture (Moscow) |

| Mastfor | Masterskaia Foreggera (Foreggers theatre-workshop) |

| MGU | Moscow State University |

| Narkompros | Peoples Commissariat of Enlightenment |

| NEP | New Economic Policy |

| NOT | scientific organization of labour |

| Okna ROSTA | Windows of the Russian Telegraph Agency, propaganda posters created by artists and poets within the ROSTA system |

| OPOIaZ | Petrograd Society for the Study of Poetic Language |

| Proletkult | Proletarskaia kultura (proletarian culture), Soviet institution to promote culture and art of working people |

| RATI | Russian Academy of Theatre Art |

| RGALI | Russian State Archive of Literature and Art |

| RGGU | Russian State Humanities University |

| RSFSR | Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic |

| tefizkult | Teatralizatsiia fizkultury (theatrialization of physical culture), a project of Ippolit Sokolov and Vsevolod Meyerhold supported by Vsevobuch |

| TEO | Theatrical Section of Narkompros |

| TsIT | Central Institute of Labour |

| UNOVIS | Utverditeli Novogo Iskusstva (The Champions of the New Art), a group of Russian artists founded by Kazimir Malevich in Vitebsk |

| Vsevobuch | Main Directorate of General Military Education |

| VSFK | All-Russian Council of Physical Culture |

Vera Mayas Studio. Photo: S. Rybin, 1927. Courtesy A. A. Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum, Moscow.

To be is to sense, to feel; in that sensing and feeling, to know, to be aware. All sensing is movement.

A young woman jumps, leaps, takes to the air. We do not know her name, only that she flies in the free dance studio of Vera dress, or relative undress for Russia at this time: her gymnasts costume and flowing tunic.

Eighty or ninety years later, the photograph has become well known, having appeared in exhibitions on modernism and physical culture and the covers of books. The woman has a public. Yet the image still has the power to undermine and to transcend description. We might be tempted to think that there is no need to say anything: this is a moment of beauty and liberation, performed not stated. The dancers jump, however, leads us to a number of large claims, the themes of our book, themes at one and the same time historical and philosophical. Our conclusions must be tentative, especially in a short book of large scope. Nevertheless, we aim to focus attention on and advance discussion of a number of related issues.