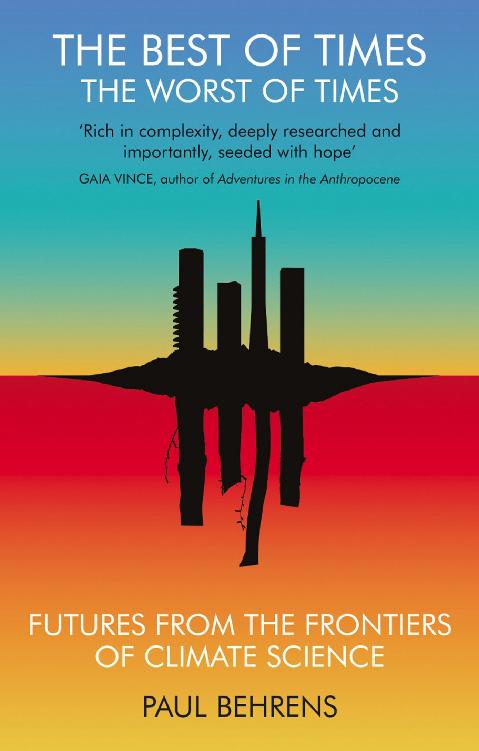

I underlined so many things I didnt know and will spend a long time considering the implications of what Ive learnt. Clear, concise, measured but urgent. Essential reading for all.

JAN CARSON

author of The Fire Starters

A powerful, up-to-date, and sometimes terrifying primer on the stupendous global problems we face today. By alternating good news and bad news chapters, Paul Behrens gives us a vivid, stereoscopic insight into the wicked challenges we humans face in coming decades.

DAVID CHRISTIAN

Professor of Russian and European History at Macquarie University and author of Origin Story: A Big History of Everything

Behrens provides a wealth of critically important facts, accessibly and insightfully related by presentations alternately slanted to pessimistic and optimistic attitudes an ideal structure for stimulating thoughtful discussion both in the classroom and public forum.

HERMAN DALY

Emeritus Professor at the School of Public Policy, University of Maryland and author of Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development

An extraordinary distillation of science, policy, and common sense without being tedious or dismal the authors grasp of the complexity and urgency of our predicament is masterful. Deserves a large global readership.

DAVID ORR

Distinguished Professor of Environmental Studies and Politics at Oberlin College Emeritus and author of Dangerous Years: Climate Change, the Long Emergency, and the Way Forward

Paul Behrenss nod to Charles Dickens in his title The Best of Times, The Worst of Times is a fitting one, for Behrens writes with the verve of a novelist, and the story he tells how our environmental future is entangled in issues of equality, employment, housing, food, energy, and much else a page-turner. While there are many books out there on the impact of climate change, I know of no other book that weighs the evidence so even-handedly, from both optimistic and pessimistic perspectives, enabling readers to evaluate the scientific data in an informed way. This is an illuminating and deeply researched book, one that deserves a wide readership.

JAMES SHAPIRO

Professor of English at Columbia University and author of Shakespeare in a Divided America: What His Plays Tell Us About Our Past and Future

Scientists have warned that tipping points could drive the Earth System past a fork in the road to two different futures. This book beautifully written with a powerful format vividly describes what these futures might look like, and how we might steer society towards a liveable future.

WILL STEFFEN

Emeritus Professor at the Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University

Behrens is the friend that gives it to you straight: unflinching on the bad stuff, but he wont crush you with despair. This book is an excellent assessment of where we are and how we might proceed, as we navigate the uncharted terrain of the Anthropocene. Rich in complexity, deeply researched and, importantly, seeded with hope.

GAIA VINCE

author of Adventures in the Anthropocene: A Journey to the Heart of the Planet We Made and Transcendence: How Humans Evolved through Fire, Language, Beauty, and Time

THE INDIGO PRESS

50 Albemarle Street

London w1s 4bd

www.theindigopress.com

The Indigo Press Publishing Limited Reg. No. 10995574

Registered Office: Wellesley House, Duke of Wellington Avenue,

Royal Arsenal, London SE18 6SS

COPYRIGHT PAUL BEHRENS 2020

This edition first published in Great Britain in 2020 by The Indigo Press

Paul Behrens asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by The Indigo Press

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978-1-911648-09-3

eBook ISBN : 978-1-911648-10-9

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Design by www.salu.io

Author photo Arash Nikkhah

Typesetting and eBook by Tetragon, London

Extract from The Principle of Hope , Ernst Bloch, 1954 reprinted courtesy of The MIT Press

For Caoilinn

Contents

Fraudulent hope is one of the greatest malefactors, even enervators, of the human race, concretely genuine hope its most dedicated benefactor.

Ernst Bloch , The Principle of Hope , 1954

Living successfully in a world of complex systems means expanding the horizons of caring. No part of the human race is separate either from other human beings or the global ecosystem. It will not be possible in this integrated world for the rich in Los Angeles to succeed if the poor in Los Angeles fail, or for Europe to succeed if Africa fails, or for the global economy to succeed if the global environment fails.

Donella Meadows , Thinking in Systems , 2008

The problem with the secular narrative is not that it assumes progress is inevitable It is the belief that the sort of advance that has been achieved in science can be reproduced in ethics and politics.

John Gray , Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia , 2007

Prologue

Do you think were going to be okay?

In the past, when I was asked what my profession was, Id say: physicist. This might have prompted a host of fun questions: Does a person running in the rain get equally wet as someone walking in the rain? Do sinks really drain anticlockwise in the southern hemisphere? If I mentioned that my masters degree was in astronomy, aliens would likely enter the conversation, or I might be asked why the solar system is flat, or if Libras are compatible with Capricorns. Communicating science has been a true joy: making complex concepts accessible to people (since the laws of physics arent exclusive everyone obeys them!), exploring the implications for science and society, hopefully fostering and sharing some awe for the world we live in. Now that my work is focused on environmental science, however, I tend to be asked a far more daunting question: Do you think were going to be okay?

Its a good question. But words always fail me. Should I assume the question relates to climate change, when they might mean another crisis, like species loss or microplastics? There is no straightforward answer to any of these problems. I could reframe the initial question: How long have we got? I find the question so troubling that when others are arguing about it at the bar or over dinner, I sometimes try not to get involved. I overhear the all-too-familiar existential monsters: insect disappearances, plastic soups, massive wildfires, catastrophic floods, disappearing glaciers, tarmac-melting temperatures, antibiotic resistance. As we live with intensifying environmental crises, these issues are inching towards the front of the newspapers. They are starting to become standard fare around the dinner table and in the media. Perhaps not every dinner table or inside every newspaper, but give it time We gloss over how unique this is. At what other point in human history would two strangers on a blind date, within five minutes of first meeting, seriously be discussing how humanity is walking, eyes wide open, into global civilizational collapse?

At the dinner table, this First World conversation plays out quite predictably, advancing to the what-can-be-done phase, unconsciously imitating the structure and flow of reports from various international institutions like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Solutions are contested: we all have to learn to consume less; corporations need to be regulated, as they dont have the next generations interests at heart; we need to stop having babies; nuclear war could render this whole discussion moot. The conversation spirals, becoming either melancholic or histrionic until someone suggests that were living in the best time in human history: that the average global life expectancy is now seventy; that child mortality rates are at an all-time low; that food, energy and commodities are more plentiful than ever. Perhaps, a little relieved, people concede that things are changing that, yes, it will be a difficult few decades but well figure it out. Look how far weve come in only a few hundred years. Solutions will be discovered . We are a resourceful species. The conversation lurches back and forth from pessimism to hope, winner to loser.