DAMMED

Critical Studies in Native History

DAMMED

The Politics of Loss and Survival in Anishinaabe Territory

Brittany Luby

Dammed: The Politics of Loss and Survival in Anishinaabe Territory

Brittany Luby 2020

24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777.

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Treaty 1 Territory

uofmpress.ca

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

Critical Studies in Native History, ISSN 1925-5888 ; 21

ISBN 978-0-88755-874-0 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-88755-876-4 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-88755-875-7 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-88755-915-0 (bound)

Cover image by Arlea Ashcroft

Cover and interior design by Jess Koroscil

Printed in Canada

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

The University of Manitoba Press acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Sport, Culture, and Heritage, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

To my ancestors who lived and died by the Winnipeg River

Your stories flow through me, and without them this work would not have been possible.

To the many children yet to be born along its banks

May you sing of the future that your ancestors envisioned.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Foreword

A Message from Chief Lorraine Cobiness

Dalles 38C Indian Reserve (now known as

The Winnipeg River goes up. The Winnipeg River goes down. Band members do not know when water levels will change (or by how much). The Lake of the Woods Control Board and Ontario Power Generation rarely inform band members of scheduled changes.

Elders from Dalles have shared their stories with me. Some people drowned. Many people lost their livelihoods. As Anishinaabe people, our ability to hunt and fish, to pick manomin (wild rice), to live off the landour ability to be self-sufficientwas taken away by the dams. Families broke up and left Dalles because of managed flooding in the 1960s and 1970s.

I can see the lingering damage of dam development on some families from Dalles. Relationships between relatives can be strained because the dams forced them apart for years. Today, when relatives share the same physical space, they sometimes seem to be disconnected.

What bothers me as Chief is the unfairness of it all. When flooding happens to other regions, such as a municipality, or to other people, such as farmers, compensation is received almost immediately. It might take a few months. It might take a year.

But Canada requires the Anishinabeg to use a separate system to see any type of flood relief. The Indian Actstill active todaysays that status Indians are different, that reserve lands are different. It takes years to negotiate settlements with Canada for the flooding of reserve lands. As Anishinaabe people, we have to fight colonialism and paternalism.

Our community is going to start demanding active consultation with the Lake of the Woods Control Board and Ontario Power Generation. We want to negotiate flooding that respects our growing season, our spawning season, and our economy. We want a future that includes rice and sturgeon.

We need the support of other Canadians if we are to face the future with hope.

We have a lot of work to do as Canadian and Anishinaabe adults. We are role models for the youth. We must teach our children how past decisions shape peoples lives and possibilities today. This book is a start.

I am optimistic that our children will work to make this country better together. When we teach history, we build common ground for the process of reconciliation. Again, this book will be a part of that process.

Ultimately, we have the same hearts and bleed the same blood. We need to acknowledge the human part of everybodys existence. At the most basic level, members of Niisaachewan Anishinaabe Nation just want to negotiate water management, human to human, in order to take care of ourselves and protect our way of life.

ChiefLorraine Cobiness, Niisaachewan Anishinaabe Nation

Transcribedand compiled by Emma Stelter, University of Guelph

April2017

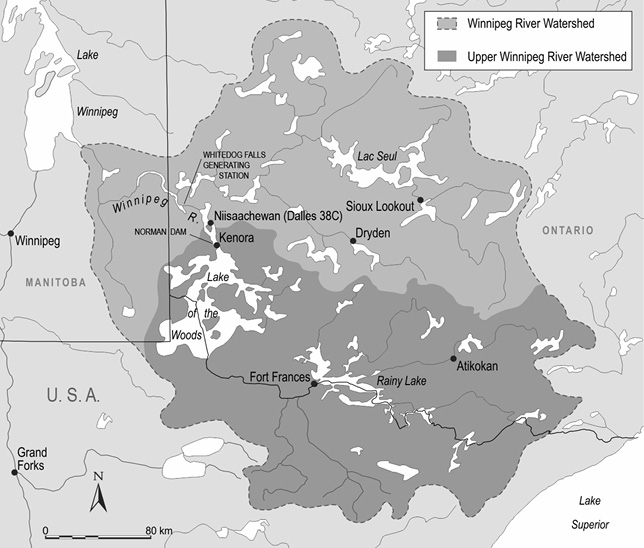

Figure 1. Map of the Winnipeg River watershed in the North American context.

Introduction

Looking Out from Anishinaabe Territory

When I close my eyes, I can still see the place of my birth: Lake of the Woods. This place is located about 180 kilometres east of the longitudinal centre of what is now known as Canada. It straddles three colonial borders, laying claim to parts of Ontario, Manitoba, and Minnesota. Kenora, my natal home, is at the north shore of Lake of the Woods. It is known for its jagged granite shoreline. It is known for islands of varying size, memorialized in verse as jade-like gems.

Controversy dominates the story of our origins. Place names suggest that the Anishinabeg originated hereor at least seventy kilometres northwest at Manitou Ahbee (Where the Creator Sits). It is likely that Gitchie Manitou (the Great Creator) envisaged humans there.

Alternative accounts suggest that the Anishinabeg migrated to northwestern Ontario from somewhere along the shores of the Great Salt Water [Atlantic Ocean] in the East around 800 ACE.

However my ancestors arrivedwhether by divine intervention, by foot as the glaciers retreated, or by canoe in search of aquatic plants or new landwhat is certain is that Lake of the Woods and its outflow channels provided sustenance from time immemorial. Each of these otherwise conflicting origin stories reveals that the Anishinabeg lived by and relied on the water. By the 1820s, my paternal ancestorsassociated with what is now known as Dalles 38C Indian Reserveoccupied a territory that extended roughly from Rough Rock Lake (near present-day Minaki, Ontario) in the north to Muskeg Bay (near present-day Warroad, Minnesota) in the south. James Redsky notes that some Indians reported there would be other Ojibways who lived in the area as far south as Kasakas-kaw-chimakak (Leech Lake, Minnesota) and as far west... eventually as the Saskatchewan River. It is unclear during which years the Ojibway (who form part of the Anishinaabe Nation) occupied this territory. We do know, however, that the Anishinabeg migrated between the north shore of Lake of the Woods and what would become Warroad, Minnesota, in the early 1800s since Redsky notes that Mis-quona-queb, an Anishinaabe leader, lived at the entrance of the Winnipeg River for a time and married a woman from Warroad.