HIGHER EXPECTATIONS

HIGHER EXPECTATIONS

OLLEGESTEACH STUDENTSWHATTHEYTO KNOW IN THEWENTY-IRSTENTURY?

DEREK BOK

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2020 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work

should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bok, Derek Curtis, author.

Title: Higher expectations : can colleges teach students what they need to know in the twenty-first century? / Derek Bok.

Description: Princeton, New Jersey : Princeton University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019056821 | ISBN 9780691205809 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Education, HigherAims and objectivesUnited States. | Education, HigherCurriculaUnited States. | College teachingUnited States. | Educational changeUnited States. | Education and globalization.

Classification: LCC LA227.4 .B666 2020 | DDC 378.73dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019056821

eISBN 9780691212357

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Peter Dougherty and Alena Chekanov

Production Editorial: Jill Harris

Text Design: Leslie Flis

Jacket Design: Leslie Flis

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Alyssa Sanford and Kate Farquhar-Thomson

Copyeditor: Cynthia Buck

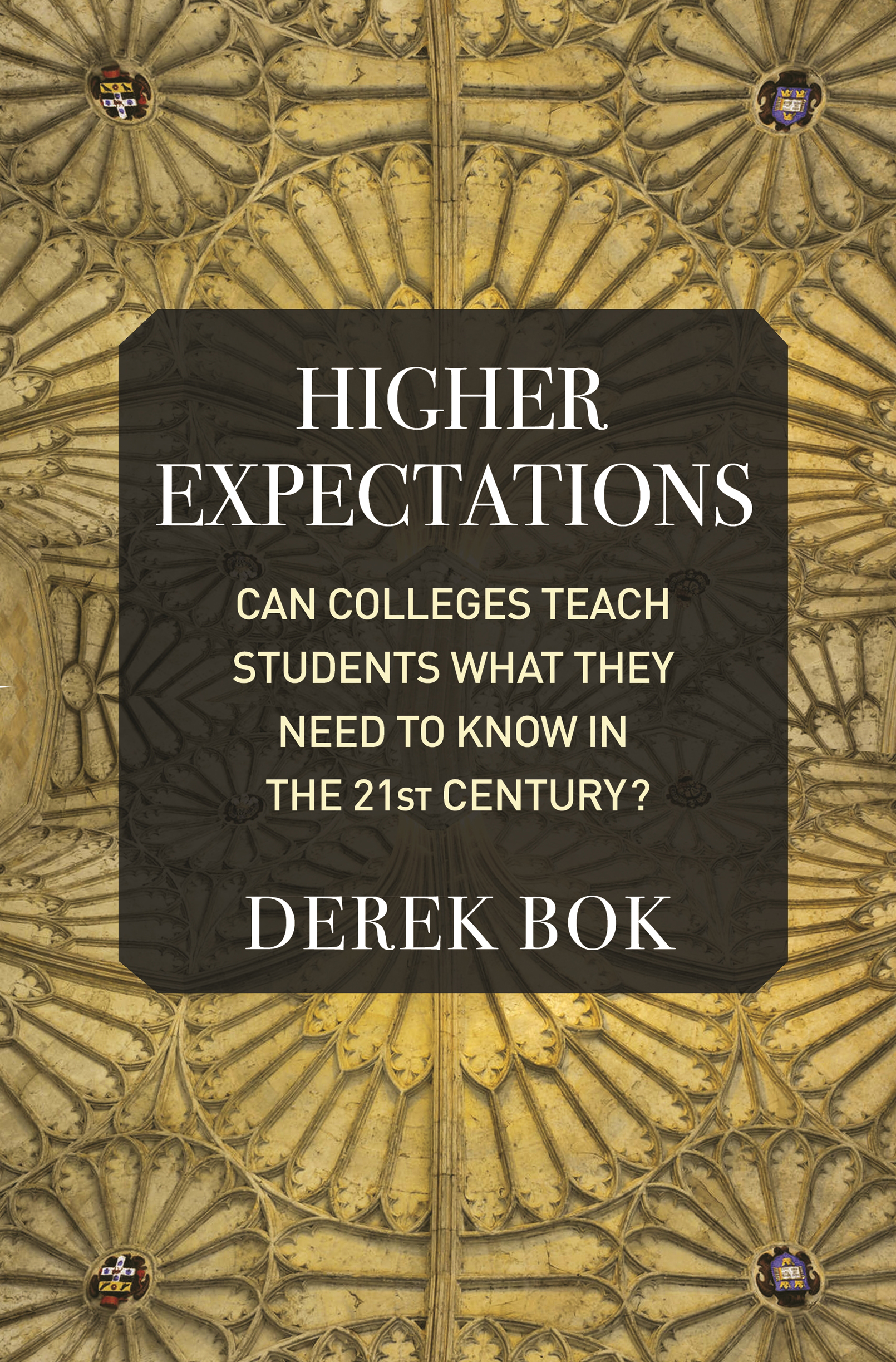

Jacket image: Ceiling in entrance hall of Christ Church, Oxford / Alamy

Preface

Higher Expectations is the culmination of seven decades of engagement with questions of teaching and learning dating back to my undergraduate days in the late 1940s, when I served as a student representative on a curriculum committee at Stanford. At age twenty, my thoughts about education were not always carefully considered. Thus, when a new president, Wallace Sterling, announced in a speech to the students that he was determined to make Stanford the Harvard of the West, I decided on the following day to write him a letter explaining why Stanford in its present form could never rival Harvard as an academic institution. My point was simply that Stanford could not make up its mind whether it should be a great academic institution, a great athletic power, or a great place for having fun and enjoying a wealth of extracurricular pursuits. Although I had never set foot on Harvards campus and knew next to nothing about the institution, I proceeded to contrast it with Stanford by describing its unswerving commitment to intellectual excellence. Until Stanford made up its mind to do likewise, I maintained, it could not hope to become the Harvard of the West.

The very next day, while waiting in line for lunch, I was approached by a member of the staff, who said that President Sterling would like to see me. Very well, I replied, I will call and make an appointment. President Sterling wishes to see you now, the emissary replied. Abandoning all thoughts of lunch, I hurried to the presidents office and engaged for the next thirty minutes in what the State Department would describe as a full and frank exchange of views in which neither of us gave ground to the other.

Decades later, in my twentieth year as Harvards president, I was asked to contribute a letter for inclusion in a book to celebrate Stanfords first one hundred year

resident Sterling. I ended my account with the statement: History will determine which of us was more nearly correct. I then signed the letter Derek Bok, Stanford of the East.

After receiving my law degree and spending almost three years in the Army, I continued my interest in education by joining the Harvard Law School faculty and chairing the curriculum committee, followed by three eventful years as dean. It was no accident, then, that when I came to be president of Harvard in 1971, I chose to make teaching and learning a priority.

I soon realized that undergraduate education occupied a lowly position on the totem pole of faculty concerns. After two decades of basking in the warming sun of continuous growth in federal funding, most professors had become preoccupied with research and graduate (PhD) training. In the mid-1960s, the faculty had made an effort to revise the curriculum but had to abandon it after failing to reach a consensus on how to move forward. That experience left everyone discouraged about the prospects for academic reform. The angry campus protests at the end of the decade over the Vietnam War and other issues had left the faculty with little enthusiasm for spending several more years of effort improving undergraduate education.

Despite these conditions, I was dismayed that such a distinguished faculty seemed unwilling to pay more attention to teaching undergraduates. After all, then as now, Harvard attracted an exceptionally talented and intellectually curious group of students. Surely they deserved the most challenging and stimulating education that their professors could provide.

I therefore decided to devote my first speech before the Faculty of Arts and Sciences to the subject of undergraduate teaching. I worked hard on the speech and felt that it had gone reasonably well until I was visited by Gerald Holton, a professor of physics who had been the youngest member of a committee formed at the end of World War II to review the college curriculum. After expressing appreciation for my choice of topics, he informed me that at least three-quarters of the faculty in the audience had given up on me entirely when I announced the subject of my address.

It is a constant challenge for a university president to try to counter the tendency of professors in the most distinguished universities to value research and publication over teaching. The incentive structure strongly favors the former over the latter. Faculty salaries nationwide also privilege research and publication, and the market compels obedience, else the most accomplished scientists and scholars will soon depart for greener pastures. Even if this imbalance were removed, the outside world would still reward successful researchers with summer stipends, prizes, consulting opportunities, and other benefits that are rarely available even to the most inspiring teachers. Under these conditions, university presidents must summon a lot of ingenuity to create and sustain a lively interest in teaching and educational reform.

Despite these difficulties, I eventually witnessed a few heartening signs of progress. After five years of patient work by my wise and widely trusted dean, Henry Rosovsky, the faculty produced a new and vastly improved curriculum. Henry managed to enlist a number of the most respected teachers and scholars to take the lead in this review. During the ensuing months, the committee made extraordinary efforts to meet with small groups of faculty to discuss its proposals and adapt them where necessary in response to the feedback it received.

As the review reached a critical stage, an unexpected development threatened to derail our efforts. Dean Rosovsky received an offer to become the next president of Yale. When he traveled to New Haven to talk with Yale officials, I feared that all was lost. To my surprise, however, he returned to Cambridge a few days later and informed me that he would stay at Harvard. When I pressed him to explain, he replied: I thought I ought to finish what I started. Moved by his example, and following some of the most interesting debates that I have ever heard at Harvard, the faculty approved the new curriculum overwhelmingly.