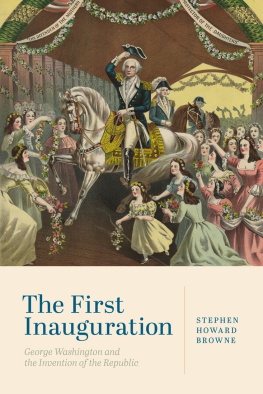

The First Inauguration

The First Inauguration

George Washington and the Invention of the Republic

Stephen Howard Browne

The Pennsylvania State University Press

University Park, Pennsylvania

An earlier version of chapter 5 was published by Michigan State University Press as Sacred Fire of Liberty: The Constitutional Origins of Washingtons First Address, Rhetoric and Public Affairs 19, no. 3 (2016): 397426.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Browne, Stephen H., author.

Title: The first inauguration : George Washington and the invention of the republic / Stephen Howard Browne.

Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Examines the first American presidential inauguration, including the people, ceremonies, and issues surrounding the event, and argues that George Washingtons inaugural address provides a compelling statement of the values necessary to make the experiment in republican government a successProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020034973 | ISBN 9780271087276 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Washington, George, 17321799Inaugurations. | Washington, George, 17321799. Inaugural address of 1789. | United StatesPolitics and government17891797.

Classification: LCC E311 .B83 2020 | DDC 973.4/1092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020034973

Copyright 2020 Stephen Howard Browne

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 168021003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z 39.481992.

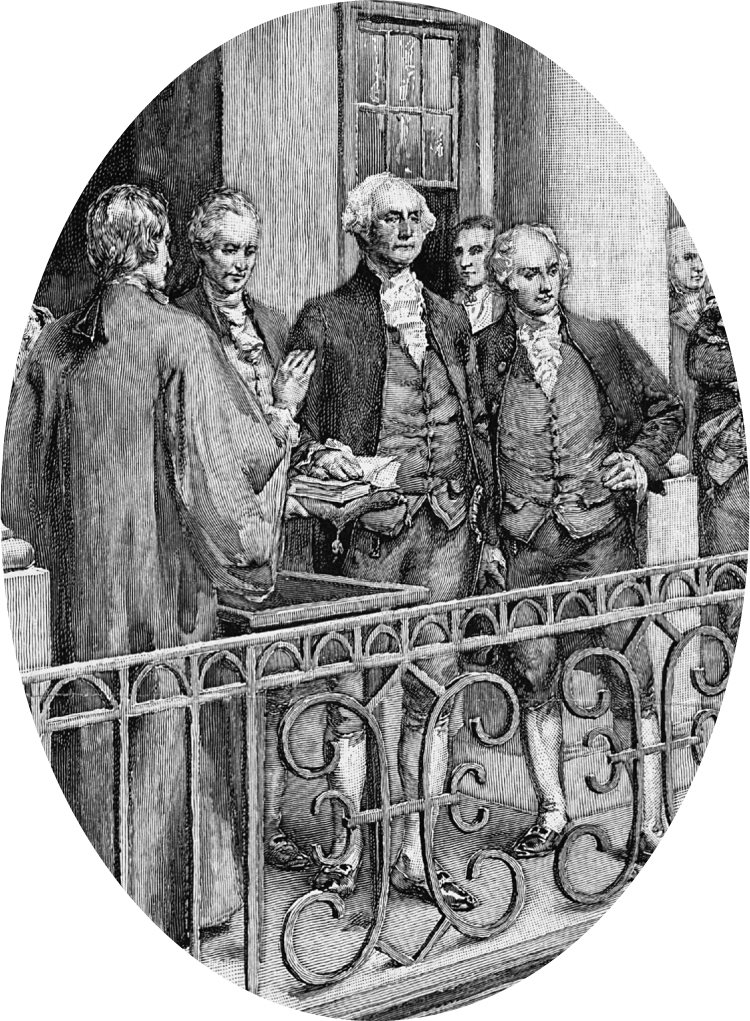

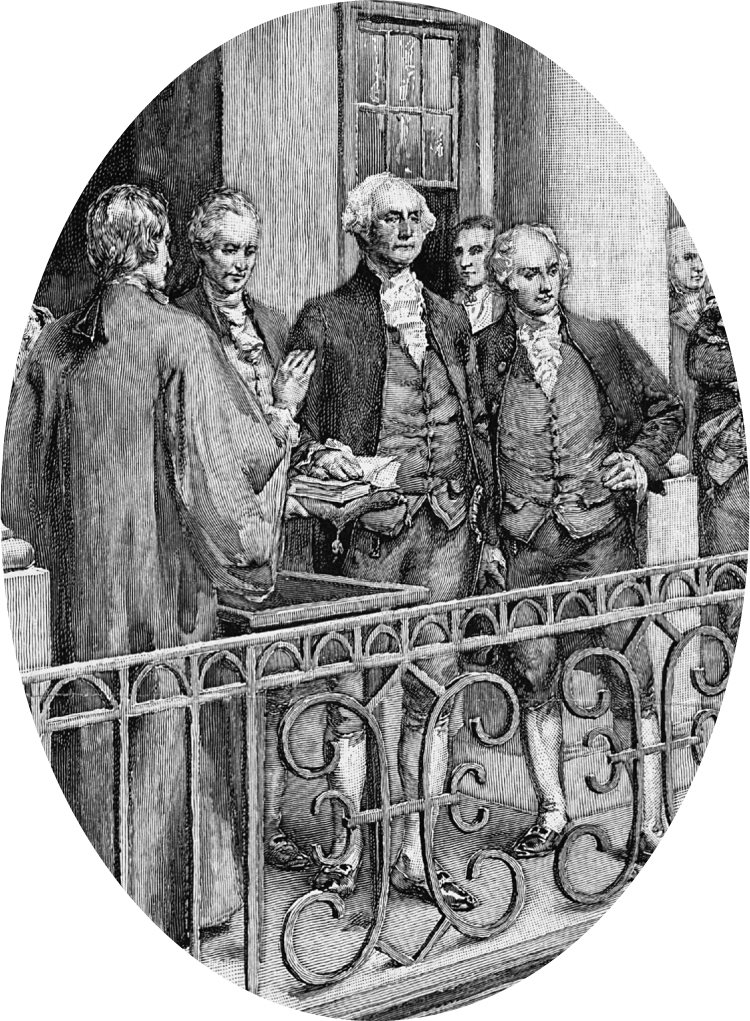

Frontispiece: detail from Washington Taking the Oath as President, April 30, 1789, on the Site of the Present Treasury Building, Wall Street, New York City. From Century Magazine, April 1889. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Divisio of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, New York Public Library Digital Collections, 815048.

For Margaret, Jessica, Maria, Emily, and Elizabeth, Once and Again, and Always

CONTENTS

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, View of Mount Vernon Looking to the North. July 17, 1796. The Portico Faces to the East (17)

Christopher Colles, survey of roads from Annapolis to Alexandria, 1789(40)

One of George Washingtons coaches(42)

Howard Pyle (artist) and F. M. Kellington (engraver), Washington Met by His Neighbors on His Way to the Inauguration, 1889(49)

James Trenchard and Charles Willson Peale, An East View of GRAY S FERRY , Near Philadelphia, With the TRIUMPHAL ARCHES , &c. Erected for the Reception of General Washington, April 20, 1789 (63)

President-Elect Washington Crosses Floating Bridge (Grays Ferry) on Inaugural Journey, Philadelphia, April 20, 1789 (64)

Sheet music for The Favorite New Federal Song, Adapted to the Presidents March, also known as Hail Columbia (76)

Reception of Washington at Trenton, New Jersey, April 21, 1789 (77)

Federal Hall on Wall St. N.Y.and Washingtons Installation 1789 (120)

Hatch and Smillie (engraver), View of the Old City Hall, Wall St. In Which Washington was Inaugurated First President of the U.S. Apl. 30, 1789, 1850(124)

The Presidential Mansion, Franklin Square, 1789 (129)

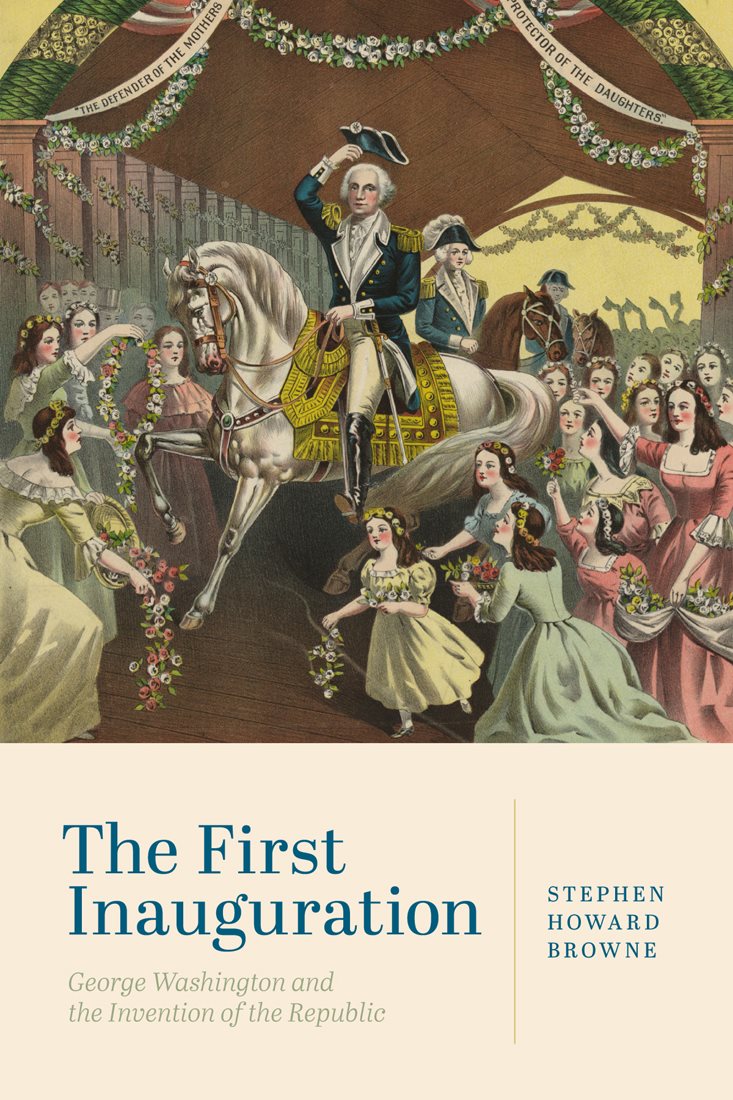

Howard Pyle, Washingtons Inauguration, 1889(137)

Washington Taking the Oath as President, April 30, 1789, On the Site of the Present Treasury Building, Wall Street, New York City (138)

I am grateful for the support of Penn State University Press and particularly for the encouragement and direction of Ryan Peterson, Kendra Boileau, and Patrick Alexander. One could not reasonably ask for a better team of professionals committed to the work, the art, of scholarly publishing. For their keen eye and helpful insights, I thank Peter Onuf and Robin Rowland; such shortcomings as this book may feature are entirely my own, of course. I was fortunate to receive research assistance and counsel from Haley Schneider, Keren Wang, Benjamin Firgens, and Dominic Manthey. This kind of support is not a given, and I am grateful to Denise Solomon, Head of the Department of Communication Arts and Sciences at Penn State, for affording me the opportunity to pursue my interests.

A special note of acknowledgment is owed to Allison Niebauer, whose rare combination of intrepidity, intelligence, patience, and goodwill assisted materially in the completion of this project. Thank you, Allison.

For their encouragement and wisdom, I am grateful to Mary Stuckey and Curtis Smith. My departmental colleagues have been a source of inspiration and support for many, many years. My thanks to you all.

I aim in this book to tell the story of George Washingtons journey to New York, of the speech he gave on April 30, 1789, and of the speechs legacy in the American tradition. The first inaugural address is this storys centerpiece. My analysis of it is designed to illustrate this simple but necessary thesis: that Washingtons performance that day established a resource for the ongoing work of realizing Americas greatest ideals. That the address has not been sufficiently recognized or availed of for this end is regrettable but not irremediable. Here, I hope to reassert the inaugural addresss claim to place in the American canon of state papersto remind us that we have in the address and in the circumstances of its delivery a rich and vital fund for thinking about the political situation in our own challenging times.

The First Inauguration is written for a readership concerned with the tenor of political discourse in our own time. Americans have always been a noisy, clamorous people. We do not shy away from debate; indeed, we seem to thrive on it as the very stuff and substance of democracy. When such give-and-take is thought to be productive, sincere, and motivated by rival conceptions of the public good, we applaud; when it appears merely partisan or self-interested, we despair. Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Henry Clay; Abraham Lincoln, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Martin Luther King Jr.titans all, and we claim them with pride as our own. Constitutional conventions, civil rights marches, declarations of independence: such eloquence. But more often, and certainly of late, we lament the passing of an age when citizens deliberated as citizens, with speeches, not tweets; with crisply argued letters to the editor, pamphlets, orations, and finely tuned sermons. That is nostalgia, but the longing is real. And still, an unmistakable note of despair may be heard, as if we have somehow lost something precious, hard, and fine about our shared humanity. Have we?

We have not. I hope to provide in the following pages a reason to believe again in ourselves, in our leaders, and in the essential dignity of the democratic quest. To those who might wonder whether yet another book on Washington is needed, I respond with a resounding yes. We need to call to mind the story of Washingtons inauguration because in it we discover vital resources for the reanimation of civic life; we need, like every generation, to invent a version of the first president to meet our own particular but hardly unique challenges. We need to listen to what he has to say because what he said and how he said it offers us a gift we cannot afford to ignore or cynically dismiss.

Next page