Contents

Guide

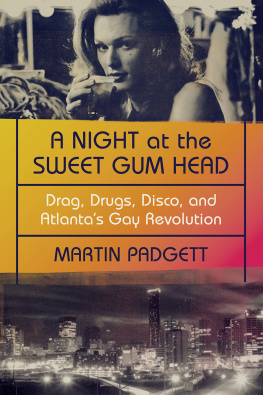

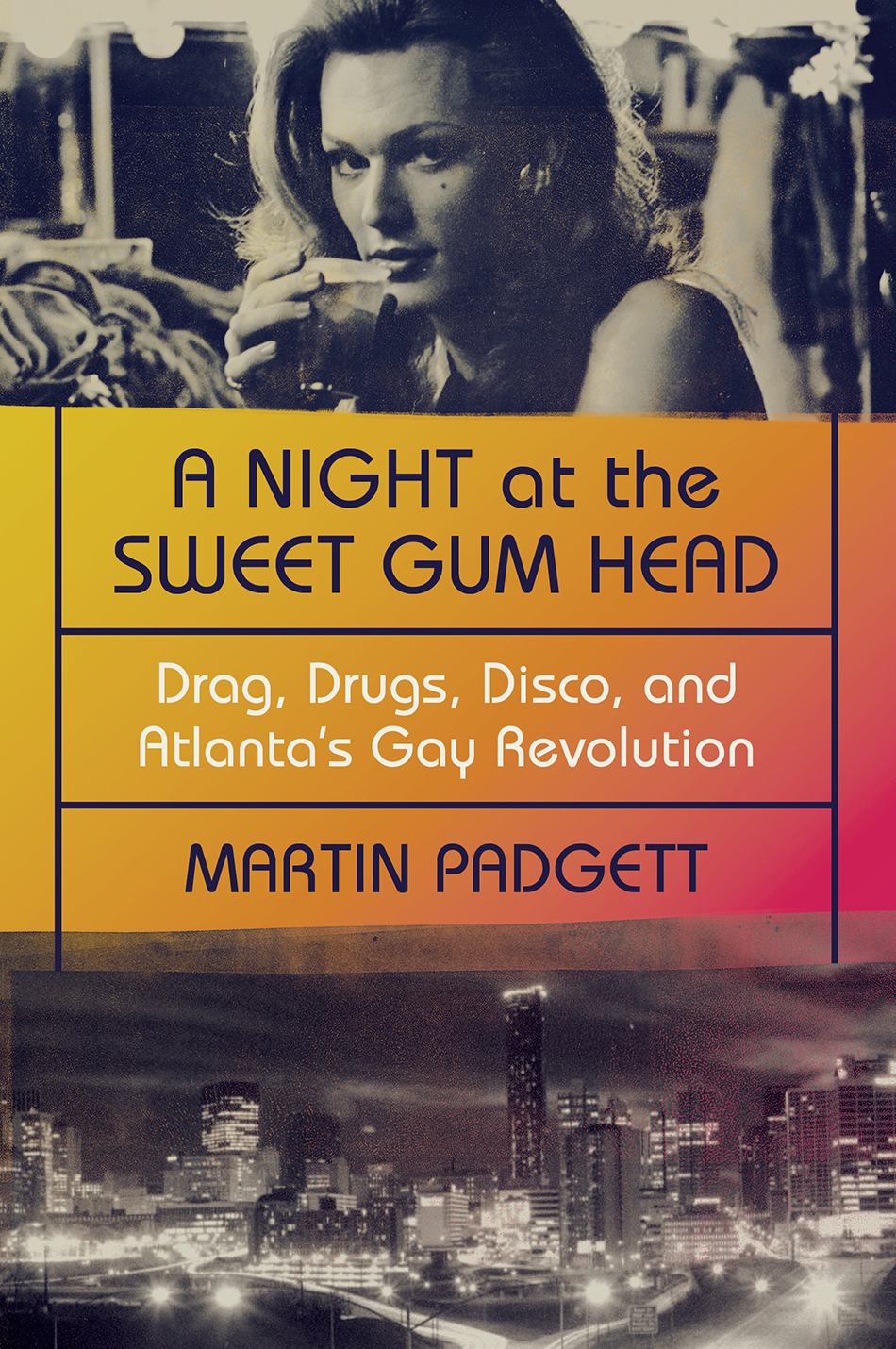

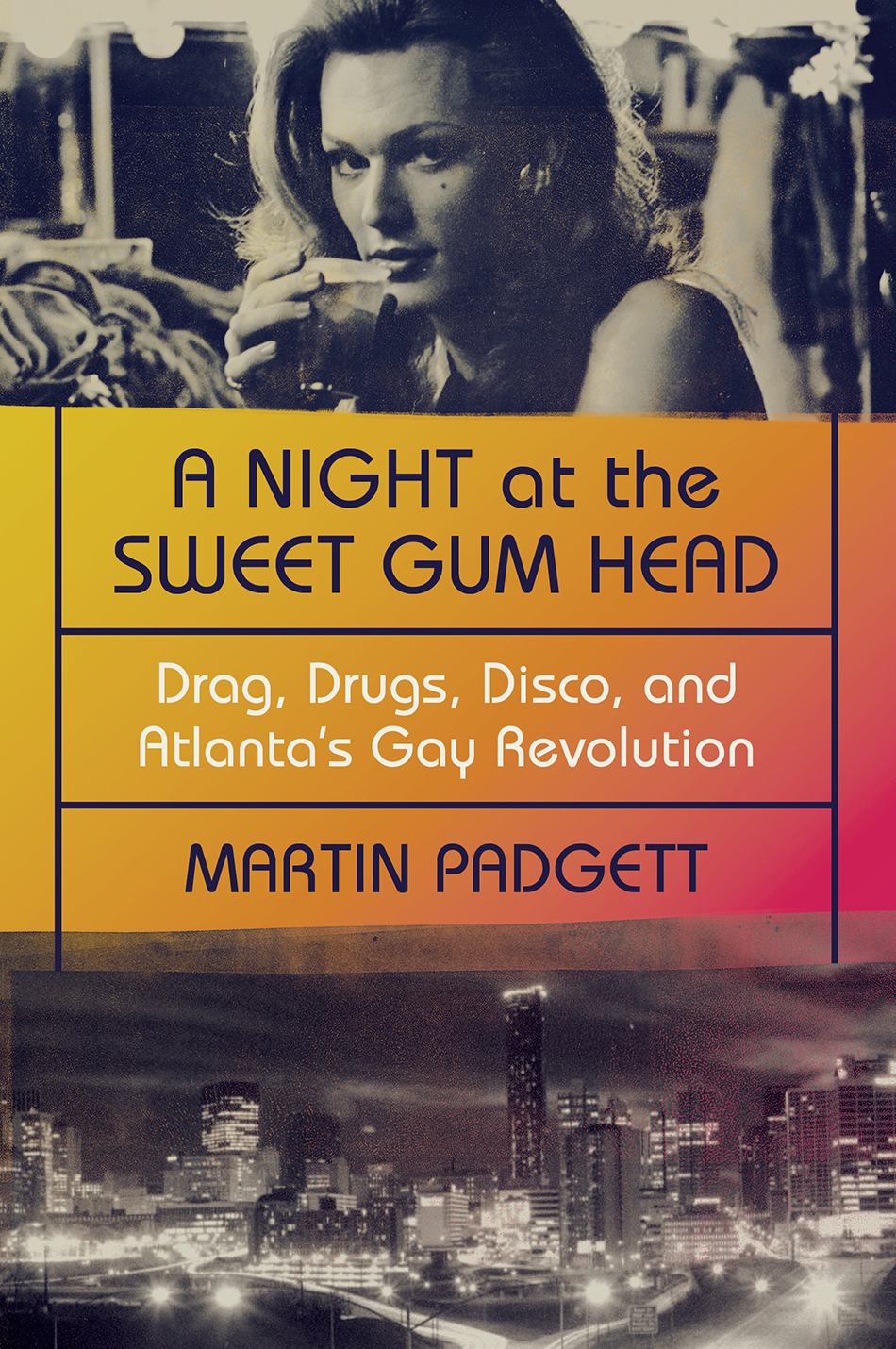

A NIGHT AT THE SWEET GUM HEAD

Drag, Drugs, Disco,and Atlantas Gay Revolution

MARTIN PADGETT

For Don, if he could see me now

Contents

I n 1996, I lived in Birmingham, Alabama, where I led a double life. I believed coming out there would come with unbearable consequences, so I kept to myself. Each weekend I arrowed east, sometimes at a hundred miles an hour, to Atlanta.

I screwed up the courage to go to my first gay bar in Atlanta. I drove down Cheshire Bridge Road, pulled into the parking lot, and took a deep breath, not knowing what to expect. When I opened the door to Hoedowns, a country-and-western joint, the catchy refrain of familiar twangy music invited me inWynonna Judds Heaven Help My Heart. On the dance floor, a carousel of men in white cowboy hats whirled in line-dance formation. Some glanced at me. I smiled back at them. I breathed a sigh of relief.

I belonged.

Two decades before, on the same stretch of road, the godfather of Atlanta gay nightlife had opened another country-and-western bar and made himself its sheriff. At the County Seat, Frank Powell built a replica of a small town inside an old warehouse, complete with wagon wheels, a country store, and a wishing well.

Powell owned more than a dozen gay bars in Atlanta from the late 1960s until he died in 1996. He built an underground universe that came to life at night, after respectable Atlanta had long gone to bed. He opened quiet drinking bars, fancy fern bars, glamorous lesbian bars, hot disco bars, and seedy hustler bars.

He named his most famous nightclub after his hometown in Florida. It was the Showplace of the South, the Sweet Gum Head.

///

T oday, American lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender people, and queers can get married. We can find short-term special friends or life partners on our smartphones. We can venture proudly and safely into the straight world outside the confines of bars and clubs once designated specifically as gay spaces.

Fifty years ago, none of those things was true. Queer people were shamed and muted, jailed, exiled, and put in danger. Often they were left no choice but to leave home, and to run away to cities where they might be accepted, or at least tolerated.

Even in those cities, gay bars were dangerous and illicit placesbut they were also the birthplace of the emerging gay rights movement. Queer communities formed, and they demanded equality. It was a time of heady optimism. Many believed anything was possible, even progress. The movement had its most visible roots in New York and San Francisco, but after it flared in the riots at the seedy Stonewall Inn tavern in 1969, it spread quickly to cities such as Atlanta, a relatively progressive oasis surrounded by ultraconservative mores.

In the 1970s, Atlantas cruisy, electric core was the Sweet Gum Head nightclub, where an intoxicating blend of drag, drugs, disco, and revolution had a pivotal role in uniting Atlantas gay civil-rights movementand in turning Stonewalls rebellion into art. The Sweet Gum Head is where Atlanta earned its reputation for top-flight female impersonation. Its where Atlanta drag came out of the closet.

Before RuPaul Charles, there was John Greenwell, who ran away from Alabama to Atlanta and found a new home at the Sweet Gum Head. John became Rachel Wellsand Rachel became a drag superstar. Along the way, John put the two halves of his life back together.

John left the marches and protests to activists like Bill Smith. A son of devout Baptists, Bill took a seat as a city commissioner, then took over the most influential gay newspaper in the South, The Barb . When his addictions and predilections were revealed, he lost everything.

Then it all died. In the same summer of 1981 when the Sweet Gum Head closed, the New York Times reported on a rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals.

///

I met my future husband just a few months after I moved to Atlanta. I hadnt come out. We dated quietly, in moments stolen and moments made, in a gray space between old friends and new.

We visited a friend in the hospital one evening in the months before protease inhibitors became widely available. Our friend had contracted pneumonia. His spirits were fine, but his prognosis was mixed. When he was admitted, his T-cell count had fallen to 2. He dubbed those two T-cells Itsy and Bitsy. They were survivors. As for him, no one could be sure.

This is what being gay will be like , I warned myself, as if it were something I could change.

I spent countless panicked, sleepless nights negotiating a new existence, one that let me be true to myself while I faced the fear that my truth could drive my life away from me, one family member at a time, one T-cell at a time.

I had run away before, and running away had exhausted me, and resolved nothing. I stood fast and brave. I survived.

Soon after I came out, a few months after that hospital visit, I bought an old Art Decostyle apartment on Cheshire Bridge Road, next door to a strip club housed in a building that had once been home to the Sweet Gum Head.

///

H istory has given us sagas of world war, the Wild West, the suffragist movement, and the civil-rights movement. Relatively few stories of the queer revolution have been recorded. Many memories of the battle for equality that followed Stonewall were deemed unimportant, or they were forgotten, or they simply faded as the community fought for its very survival as the AIDS era dawned. History is a bridge made of sand.

I hope this story reclaims some of the joy and optimism of that brief time, and that it charts new constellations for future generations to study. As for me, its something of a memoir. In many ways, John and Bill and I have lived the same life, in our search for the place we call home, in search of our true selves.

That search always is urgent, but its particularly urgent now. While same-sex marriage has normalized aspects of our queer lives to a degree, assimilation is one of many things that have eroded our sense of community. Were losing a distinct dimension of the queer experience. Were being straightwashed, even as an unashamed army of bigots wants to turn back the clock.

This story marks our progress, but should also remind us that progress is fragile and requires regular upkeep and maintenance and, occasionally, righteous anger. We must pass on these lessons and legends before they are lost. Before we are lost.

This isnt my story of Atlanta. Its mine too. It belongs to us. This is our story of freedom.

Atlanta, Georgia

June 28, 2020

A NIGHT AT THE SWEET GUM HEAD

Atlanta

August 1969 December 1970

T hey each paid a dollar to the cashier at the office desk in the narrow lobby, and made their way toward a theater cloaked in fireproof turquoise curtainsamong them, a woman in tight brown curls and wide, hopeful eyes; a man eager to see breasts onscreen; a woman eager to see them too.

A red carpet laid out in Oscars style led them down the aisle toward Andy Warhols Lonesome Cowboys , in its third week at the theater despite terrible reviews. They whispered and giggled and chatted; the girl with wide eyes ate a submarine sandwich, while others munched on popcorn. They had filled about half the sea-green, rocking-chair seats when the Simplex projector woke up and lit the screen with images of naked bodies, quick-cut visuals, and non-sequitur plot points.

Cowboys had cost Warhols Factory just $3,000 to produce, and none of the money seemed to have been spent on the script. Men thrusted their pelvises in each others faces, the camera stared blankly at naked torsos and buttocks and breasts, and actors indulged in some lightly comic cross-dressing. The nonsensical parody of western films grated on the sensibilities of high-minded cinema.