CONTENTS

Originally published in 1957 by Hollis and Carter limited, London.

Published 2007 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14

4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2007 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2006050058

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sedlmayr, Hans, 1896

[Verlust der Mitte. English]

Art in crisis : the lost center / Hans Sedlmayr ; with a new introduction by Roger

Kimball; translated by Brian Battershaw.

p. cm.

Translation of: Verlust der Mitte. Salzburg : O. Miiller, 1951.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-4128-0607-0 (alk. paper)

1. Art, European19 century. 2. Art, European20th century.

3. ArtPhilosophy. I. Title.

N66757.S4413 2006

709'.03dc22

2006050058

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-0607-7 (pbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this book but points out that some imperfections from the original may be apparent.

CONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

The Theme

Limitations of the Thesis

Part One

SYMPTOMS

Part Two

DIAGNOSIS AND PROGRESS OF THE DISEASE

Part Three

TOWARDS A PROGNOSIS AND A FINAL JUDGEMENT

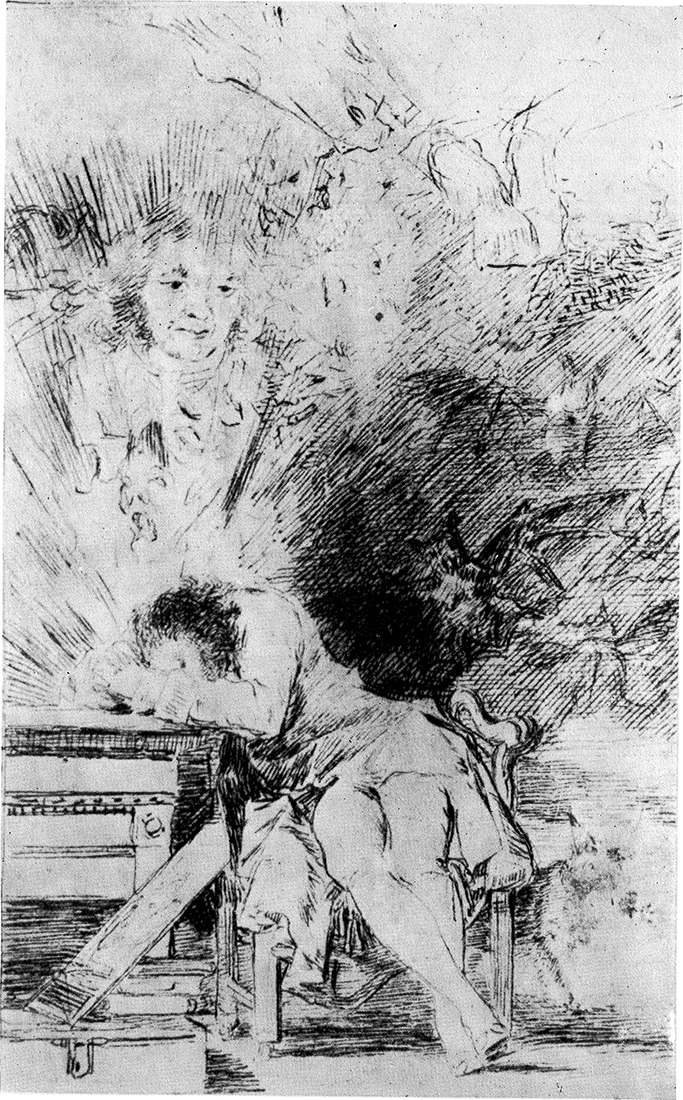

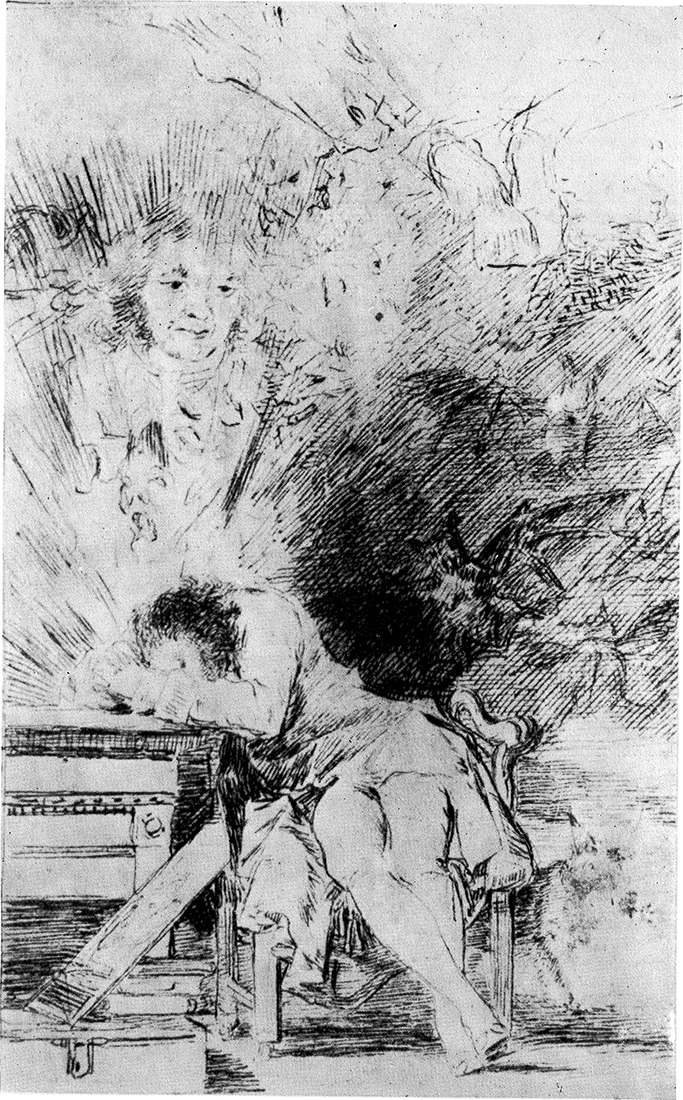

GOYA: DRAWING FOR TITLE PAGE OF LOS CAPRICHOS When reason dreams, monsters are born. (See page 141.)

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold...

W B. Yeats

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Goya: Drawing for title page of Los Caprichos

Ledoux: Charcoal Kiln in the form of a pyramid

Ledoux: Cube House

Ledoux: Spherical House for a Bailiff

Ledoux: Circular House for a Wheelwright

Boullee: Cenotaph for Newton

Mausoleum in a half pyramid

Stadium for 300,000 spectators

City Gate

Gilly: Design for a Blast Furnace, 1804

Schinkel: Altes Museum in Berlin

13. Schinkel: Two designs for the Werdersche Kirche in Berlin, 1824-1825

Schinkel: Design for a Department Store, 1827

Horeau: Design for an Exhibition Hall in cast iron, 1837

Paxton: Crystal Palace, built for the Great Exhibition in London, 1851

Semper: Design for the Richard Wagner Festival Theatre in Munich, 1864

Cottancin: Palais des Machines for the 1889 International Exhibition in Paris

Gropius: The FagusWorks in Alfeld on Leine, 1912

Tony Gamier: Design for Central Station, 1901-4

Diagram of an American Warehouse

Leonidov: Design for a spherical building of steel and glass for a Lenin Institute near Moscow

Le Corbusier: Villa Savoye, Poissy, 1930

Le Corbusier: Apartment, 1929

Le Corbusier: Model of a Skyscraper in Algiers set on a steep slope, 1933

Flaxman: Hermes conducting the Shades of the Suitors to Hades

Turner: Storm at Sea, 1844

Goya: Demons in flight

Goya: Chronos devouring his Children

C. D. Friedrich: Mountain Calvary

C. D. Friedrich: The Wreck of the Hoffnung

Daumier: The Washerwoman

Daumier: Pygmalion

Delacroix: Sketch for the Ceiling of the Galerie dApollon in the Louvre, 1849

Grandville: Dream Transformations

Ensor: Insect Family

Elisor: Christ in Agony, 1888

Ensor: Masks confronting Death, 1888

Czanne: Landscape with Bridge, 1888-9

Picasso: Woman Ironing, 1903

Picasso: The Old Guitarist, 1903

Picasso: Street Singer, 1923

Kokoschka: Still life with Skinned Sheep

George Grosz: Draped Figure, 1936

Dal: The Temptation of St. Anthony, 1936

Rodin: The Tumbler

Rodin: Meditation

Rodin: The Cathedral

Maillol: Reclining Figure

[Today] we find a pursuit of illusions of artistic progress, of personal peculiarity, of the new style, of unsuspected possibilities, theoretical babble, pretentious fashionable artists, weight-lifters with cardboard dumb-bells.... What do we possess today as art? A faked music, filled with artificial noisiness of massed instruments; a failed painting, full of idiotic, exotic and showcard effects, that every ten years or so concocts out of the form-wealth of millennia some new style which is in fact no style at all since everyone does as he pleases.... We cease to be able to date anything within centuries, let alone decades, by the language of its ornamentation. So it has been in the Last Act of all Cultures.

Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West

Beauty is the battlefield where God and the devil war for the soul of man.

Fyodor Dostoyevski, The Brothers Karamazov

Among the more remarkable books I first encountered in graduate school was a blistering polemic called (in English) Art in Crisis: The Lost Center. It was already long out of printand mores the pity. There is nothing else quite like it in the annals of conservative cultural speculation. The author was Hans Sedlmayr, an Austrian art and architectural historian whose primary field of expertise was Baroque architecture. Sedlmayr (18961984) was a founding member of the New Vienna School of art historians, a group that flourished in the late 1920s and 1930s and included Fritz Novotny and Otto Pcht (whose book The Practice of Art Historywas one of those omnivorous explanatory concepts that set susceptible academic hearts beating faster for two or three generations. Riegl believed that there was an intrinsic evolutionary logic to the development of artistic styles, one whose career (or careers) he and his successors proposed to trace and ruminate about.

It was a fertile ideafertile, anyway, in the production of papers and books. Sedlmayr edited a collection of Riegls essays in 1929 and, in 1931, published an essay called Zu einer strengen Kunstwis- senschaftToward a Rigorous Study of Artwhich distinguished between two approaches to the study of art. The first, empirical, approach focused on such pedestrian issues as provenance, chronology, influence, and patronage. The second, more exciting, approach endeavored to ride the wave of the Kunstwollen, to intuit the inner organization of the work of art. Both approaches, Sedlmayr said, were necessary to the discipline of art history, but the second (surprise, surprise) was more essential and more valuable than the first.