Table of Contents

Landmarks

Table of Contents

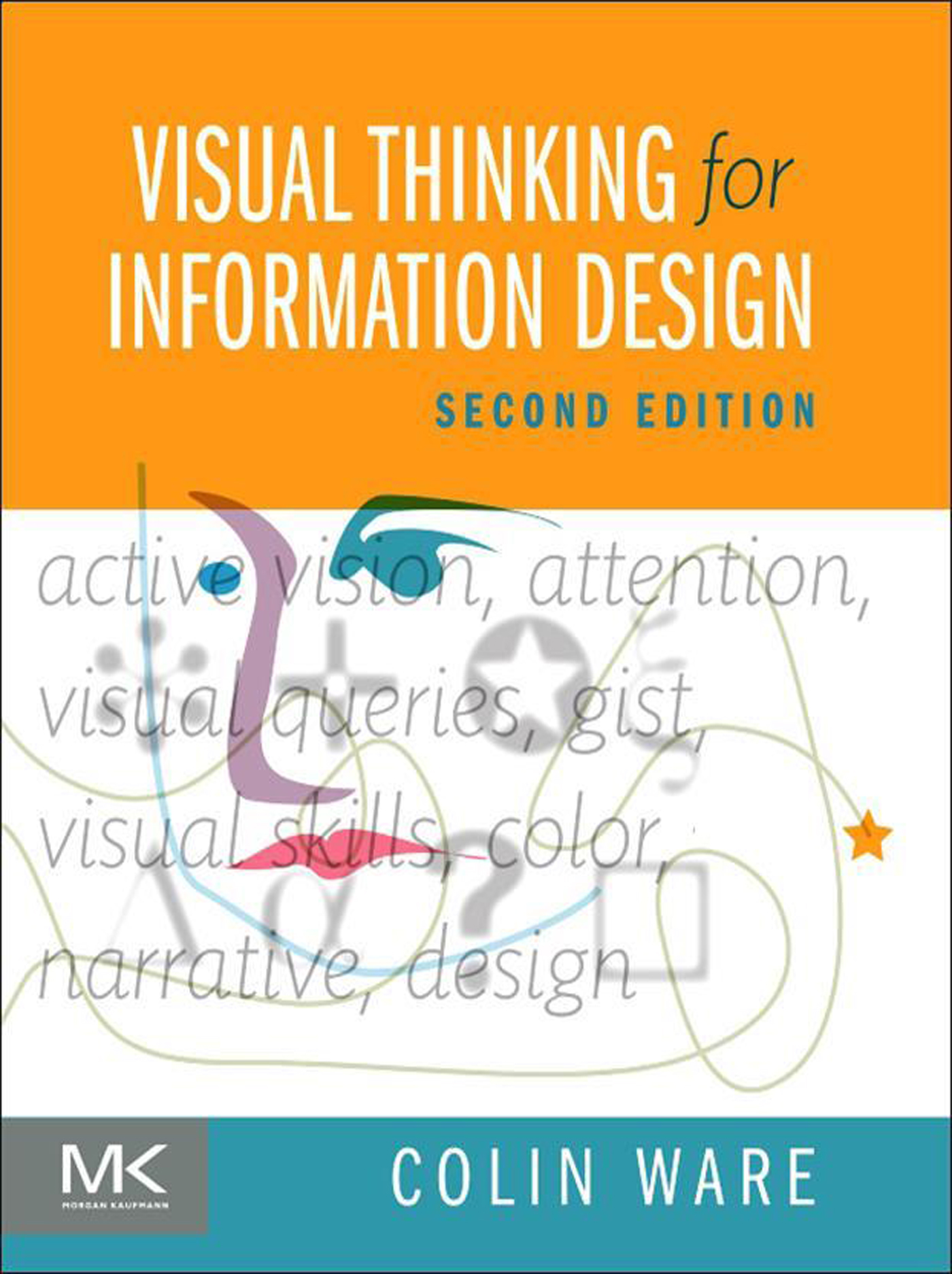

Visual Thinking For Information Design

Second Edition

Colin Ware

Copyright

Morgan Kaufmann is an imprint of Elsevier

50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States

Copyright 2022 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publishers permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein).

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-0-12-823567-6

For Information on all Morgan Kaufmann publications visit our website at https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: Katey Birtcher

Acquisitions Editor: Steve Merken

Editorial Project Manager: Alice Grant

Production Project Manager: Manikandan Chandrasekaran

Cover Designer: Brian Salisbury

Typeset by MPS Limited, Chennai, India

Printed in India

Last digit is the print number: 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Preface

Colin Ware

, which is about the design of presentation visuals.

This book also embraces the active vision theory of human perception, which predates predictive cognition and provides its foundation. Active vision means that we should think about graphic designs as cognitive tools, enhancing and extending our brains. Although we can, to some extent, form mental images in our heads, we do much better when those images are out in the world, on paper or on computer screen. Diagrams, maps, web pages, information graphics, visual instructions, and technical illustrations all help us to solve problems through a process of visual thinking. We are all cognitive cyborgs in this Internet age in the sense that we rely heavily on cognitive tools to amplify our mental abilities. Visual thinking tools are especially important because they harness the visual pattern-finding part of the brain. Almost half the brain is devoted to the visual sense, and the visual brain is exquisitely capable of interpreting graphical patterns, even scribbles, in many different ways. Often, to see a pattern is to understand the solution to a problem.

The active vision revolution is all about understanding perception as a dynamic process. Scientists used to think that we had rich images of the world in our heads built up from the information coming in through the eyes. Now we know that we only have the illusion of seeing the world in detail. In fact, the brain grabs just those fragments that are needed to execute the current mental activity. The brain directs the eyes to move, tunes up parts of itself to receive the expected input, and extracts exactly what is needed for our current thinking activity, whether that is reading a map, making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, or looking at a poster. Our impression of a rich detailed world comes from the fact that we have the capability to extract anything we want at any moment through a movement of the eye that is literally faster than thought. This is automatic and so quick that we are unaware of doing it, giving us the illusion that we see stable detailed reality everywhere. The process of visual thinking is a kind of dance with the environment with some information stored internally and some externally, and it is by understanding this dance that we can understand how graphic designs can help us think.

Active vision has profound implications for design, and this is the subject of this book.

It is a book about how we think visually and what that understanding can tell us about how to design visual images. Understanding active vision tells us which colors and shapes will stand out clearly, how to organize space, and when we should use images instead of words to convey an idea.

Early on in the writing and image creation process I decided to eat my own dog food and apply active vision-based principles to the design of this book. One of these principles being that when text and images are related, they should be placed in close proximity. This is not as easy as it sounds. It turns out that there is a reason why there are labeled figure legends in academic publishing (e.g., Figure 1, Figure 2, etc.). It makes the job of the compositor much easier. A compositor is a person whose specialty is to pack images and words on the page without reading the text. This leads to the labeled figure and the parenthetical phrase often found in academic publishing, see Figure X. This formula means that Figure X need not be on the same page as the accompanying text. It is a bad idea from the design perspective and a good idea from the perspective of the publisher. I decided to integrate text and words and avoid the use of see Figure X, and the result was a difficult process and some conflict with a modern publishing house that does not, for example, invite authors to design meetings, even when the book is about design. The result is something of a design compromise, but I am grateful to the individuals at Elsevier who helped me with what has been a challenging exercise.

There are many people who have helped. Diane Cerra with Elsevier was patient with the difficult demands I made and full of helpful advice when I needed it. Denise Penrose guided me through the later stages and came up with the compromise solution that is realized in these pages. Dennis Shaeffer and Alisa Andreola helped with the design, and Mary James with the production process. My wife, Dianne Ramey, read the whole thing twice and fixed a very great number of grammar and punctuation errors. I am very grateful to Paul Catanese of the New Media Department at San Francisco State University and David Laidlaw of the Computer Graphics Group at Brown University who provided content reviews and told me what was clear and what was not. I did major revisions to as a result of their input. For the second edition, Alice Grant and Manikandan Chandrasekaran helped with the production process.