Illustrations by Thomas Shafee

the secret world of sleep

The Surprising Science of the Mind at Rest

Penelope A. Lewis

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

contents

acknowledgments

Id like to thank all of the colleagues who have kindly helped with the research and fact-checking for this book, including Gorana Pobric and Patti Adank for the basics of the nervous system and brain anatomy; Simon Kyle for sleep physiology; Sue Llwellyn and Mark Blagrove for dreams; Jim Horne for the ubiquity of sleep and impacts of sleep deprivation; Rebecca Elliott and Deborah Talmi for emotion and emotional memory; and Dave Jones for the guerrilla guide to getting enough sleep. Special thanks also goes to Isabel Hutchinson for proofreading the entire manuscript and making many useful suggestions. Thanks also to my parents for their continual support and for their tireless proofreading and grammar-checking.

one

why sleep?

Do amoebas sleep? There are certainly times when they ball up and become inactive, but the true answer to this question depends on how you define sleepand it turns out that theres more than one way to do that.

Using minimalist criteria, sleep can be thought of as an inactive time during which an organism responds less than usual when poked or disturbed, but from which it can be roused if danger threatens. This inactivity seems to have a purpose, since animals that are disturbed during such sleep invariably try to make up for it later on (we call this rebound sleep). Under this loose definition, amoebas actually do sleep. They stop moving, ball up, and become unresponsive even when prodded. They do this for hours at a time, normally at night, and they exhibit rebound if kept on the move and deprived of this restful state. Insects, fish, and amphibians also sleep. In fact, every member of the animal kingdom appears to snooze at one point or another. In the case of wasps and others with antennae, this is particularly obvious since these appendages tend to droop when they snooze, signaling relaxed inattention to the environment.

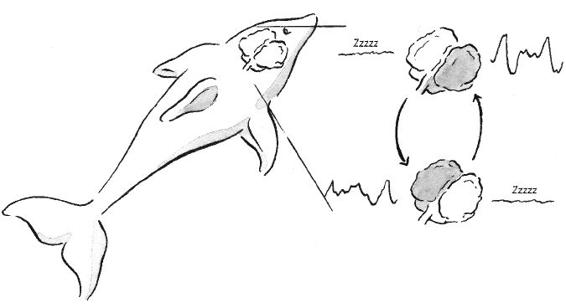

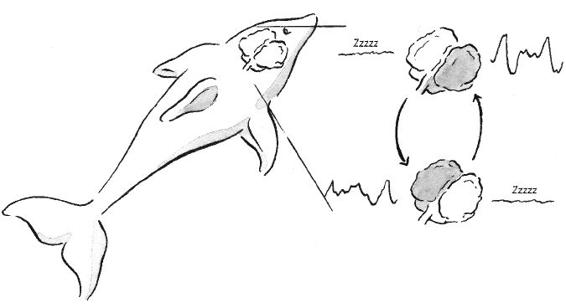

Is sleep just something animals do when there are no demands on their time? Quite the reverse: Sleep is often a risky business. Most animals live in a predatory environment in which they are extremely vulnerable when they are not alert to surrounding danger. Many creatures could easily end up as a tasty snack if a predator manages to sneak up on them without being detected. This isnt only true for tender little critters like mice, parakeets, and tadpoles. Giraffes, for instance, take about 15 seconds to get to their feet after lying down for a snooze, so they are out of luck if a hungry lion happens to be in the area (it is probably for this reason that giraffes mainly sleep standing up or leaning against a tree, yet they also need to lie down for a short time every night to get some high-quality zzzzs). Split brain sleep poses an interesting question regarding consciousness: Is an animal truly awake or aware when only one hemisphere is active?

Functions of Sleep

So what is the purpose of sleep? Surely something which is so widespread across the animal kingdom yet so dangerous and time-consuming must serve an important function. Alan Rechtschaffen, an important player in the history of sleep research, once said, If sleep does not serve an absolutely vital function then it is the biggest mistake the evolutionary process has ever made. As this statement suggests, scientists are reasonably unified in agreeing that sleep must be important, but ideas about why it is important vary hugely. One popular suggestion is that snoozing is a way to save energy. After all, animals dont normally move around a lot while they are asleep (unless we are talking about dolphins or other split-brain sleepers), so this state of inactivity must surely save some energy. This is a tempting hypothesis. We know, for instance, that many animals hibernate in order to save energy and hibernation shares many superficial characteristics with sleepbut hibernation typically lasts for months at a time, and body temperatures fall much lower during such periods than during sleep (sometimes to just a few degrees above freezing). Many animals actually warm up during hibernation in order to obtain a proper snooze. This means they are investing energy in order to get some sleepsuggesting that such slumber cant exist simply to make energy savings.

Another way to try and work out why sleep is important is by seeing what happens when we dont get enough of it. Sleep deprivation has been studied in great depthfrom crude protocols in rats, who have been deprived of sleep to the point of death in many cruel experiments, to more carefully controlled experimentation on humans, whose brains, hormonal profiles, and ability to attend, remember, and make decisions have all been carefully analyzed after more limited periods of deprivation.

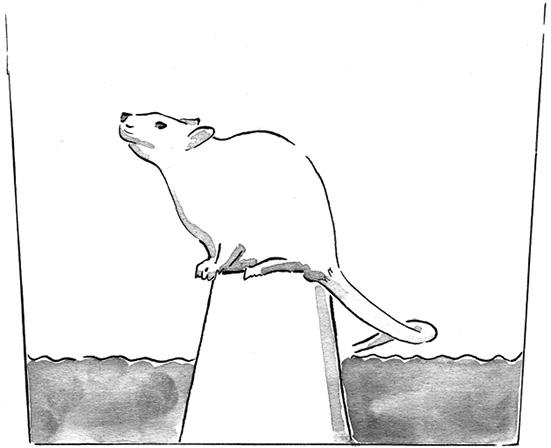

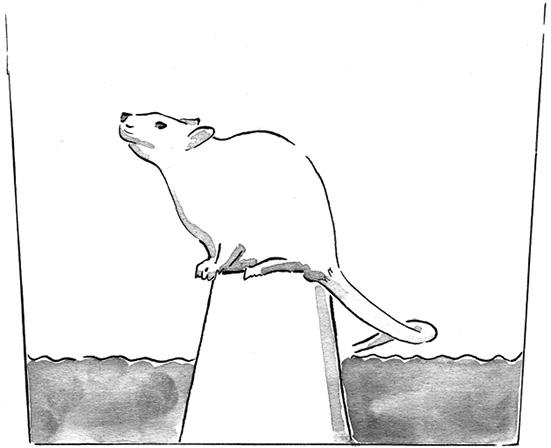

In one classic experiment, rats were housed on top of upside-down flowerpots in the middle of a pool of water. The flowerpot platform was above the water but small enough that the rats fell off it (and got wet!) whenever their muscles went limp (Fig. 1). Since one stage of sleep (REM, or rapid eye movement sleep) is characterized by total limpness of bodily muscles, this effectively meant the rats had a nasty wet awakening every time they reached this sleep stage. Rats who were treated in this way soon lost control of their body temperature, lost weight, and developed skin lesions. Within a few weeks they were all dead. This study suggests that sleep is important for temperature regulation and health in general (i.e., lack of deep sleep eventually leads to death), but it has been heavily criticized due to the excessive stress these rats suffered.

Fig. 1 Rat on top of inverted flowerpot

Studies of sleep deprivation in humans have typically involved much less stressful situations in which, though deprived for long periods (sometimes 11 days or more!), participants are otherwise treated very carefully, know they can bow out of the experiment at any time if they really want to, and therefore have little real cause for anxiety. Nevertheless, these types of experiments have shown that sleep deprivation leads to an increase in the stress hormone cortisol, a small drop in body temperature, and compromised immune function. This suggests that, at the physical level, sleep plays a role in the maintenance of body temperature and immune response. Although not negligible, these effects are a far cry from the drastic responses seen in the rat martyrs of the infamous flowerpot experiment.

More striking than the physical effects, however, are the psychological impacts of sleep deprivation. There is no need to tell you that we humans tend to feel pretty lousy if we dont get enough sleep. Perhaps the most extreme example of this comes from the story of Randy Gardner, a 17-year-old who stayed awake for 11 nights in 1965 (a record at the time) as part of a school science project. In the first few days, Gardner had problems focusing and repeating simple tongue twisters. By the fourth day he showed memory loss and had minor hallucinations (e.g., imagining a street light was a person). After a week his speech had become slow and slurred, and by days nine and ten he had more marked cognitive impairmentsfor instance, when counting back from 100 he stopped at 65, apparently because he couldnt remember what he was doing. He also showed signs of paranoia, and his speech was slow and without intonation. However, Gardners movement-based skills did not seem to be impaired. He won a game of pinball against a non-sleep-deprived interviewer on the tenth day of his ordeal. Although he had lost about 90 hours of sleep, Gardner only made up about 11 by oversleeping after the experiment, and he showed no evidence of long-term ill effects (though he was not, perhaps, monitored as thoroughly as he would be if such an experiment were to be conducted today, and I would certainly not recommend that any readers try this for themselves).