| Mwalimu: | Hujambo, bibi (au Hujambo, ndugu). |

| Mwanafunzi: | Sijambo, mwalimu. |

| Mwalimu: | Habari za asubuhi? |

| Mwanafunzi: | Nzuri. |

| Mwalimu: | Hujambo, bibi (au Hujambo, ndugu). |

| Mwanafunzi: | Sijambo, mwalimu. |

| Mwalimu: | Habari za asubuhi? |

| Mwanafunzi: | Nzuri sana. |

| Mwanafunzi wa kwanza: | Hujambo, bwana/bibi/ndugu. |

| Mwanafunzi wa pili: | Sijambo, bwana/bibi/ndugu. |

| Mwanafunzi wa kwanza: | Habari za mchana? |

| Mwanafunzi wa pili: | Nzuri sana, na wewe je? |

| Mwanafunzi wa kwanza: | Salama tu. |

MAZOEZI

1. Zoezi la kwanza

| Mwalimu: | Wanafunzi: |

| Sema, hujambo. | Hujambo. |

| Sema, hujambo, bwana. | Hujambo, bwana. |

| Sema, sijambo. | Sijambo. |

| Sema, sijambo, bibi. | Sijambo, bibi. |

| Sema, hujambo, ndugu. | Hujambo, ndugu. |

| Sema, salama tu. | Salama tu. |

2. Zoezi la pili

| Mwalimu: Wewe sema, hujambo, na wewe itika, sijambo. |

| Mwanafunzi wa kwanza: | Hujambo. |

| Mwanafunzi wa pili: | Sijambo. |

3. Zoezi la tatu

| Mwalimu: Wewe sema, habari gani, na wewe itika, nzuri. |

| Mwanafunzi wa kwanza: | Habari gani? |

| Mwanafunzi wa pili: | Nzuri. |

4. Zoezi la nne

| Mwalimu: | Juma, mwamkie, Adija. |

| Juma: | Hujambo, Adija. |

| Adija: | Sijambo, Juma. |

| Juma: | Habari gani? |

| Adija: | Habari nzuri. |

Mwalimu anafundisha maamkio. Yeye anasema, "Bwana, sema hujambo. Mwanafunzi anaitika, "Hujambo." Sasa mwalimu anasema, "Wewe, bibi, sema sijambo. Na yeye anaitika, "Sijambo." Mwalimu anasema, "Basi, sasa, wewe sema hujambo na wewe itika sijambo. Wanafunzi wanasema, "Hujambo" na "sijambo." Mmoja anasema "hujambo" na mwingine anasema "sijambo." Mwalimu anasema, "Haya, basi, vizuri sana."

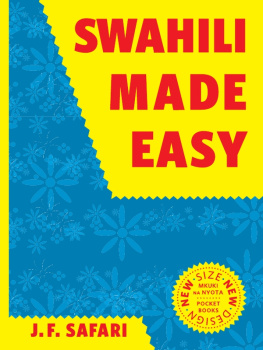

Normally a form of jambo is the opening greeting when two Swahili speakers greet one another; there is, however, variation from speaker to speaker and from one area to another in how this greeting is used. In some areas of East Africa, often in those places frequented by tourists, it is common to be greeted with just jambo itself. But the full form hujambo and its response sijambo are preferred by most native and standard speakers of Swahili.

Jambo (plural mambo) is a noun meaning 'affair, matter, thing, etc.' Hujambo is a complex grammatical form meaning 'you have nothing the matter with you, do you?' and sijambo means 'I have nothing the matter with me', thus 'Tm fine.'

Habari literally means 'news', thus habari gani means 'what sort of news?', i.e., 'how are things?' This can be modified to ask more directly about different things, e.g., habari za asubuhi (lit. 'news of [the] morning'), thus 'how are things this morning?' Habari za mchana is literally 'news of the afternoon', thus 'how are things this afternoon?' Another use of habari za meaning 'about' is seen in the heading of this section: habari za sarufi 'news of grammar' or 'about grammar'.

Responses to habari greetings vary, but nzuri is appropriate. Other forms of this greeting and responses can be found in following lessons.

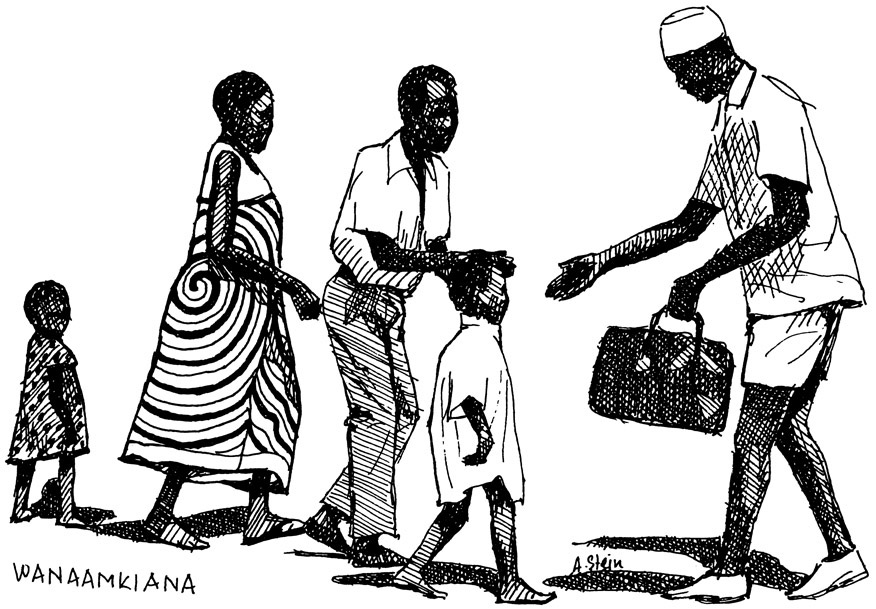

Greetings are very important social interchanges for people living on the East African coast, and by people in the rural areas throughout East Africa. After the initial greetings (as in the sample conversations beginning this lesson) a person often continues on and asks about the family, farm, business, and other personal matters. Generally, younger people are expected to greet older people first. In cities and larger towns, where the pace of life is much quicker, and impersonal, greetings tend to be perfunctory and less formal, as they are in most Western societies.

Titles are generally used in greeting others. Men are addressed with the title bwana 'mr., sir' and women with bibi (or by bi) 'mrs., ms., miss'. Unlike English, proper names do not have to be used with bwana, bibi, and other titles., but may be, if the speaker desires. It is also not unusual to hear a title used with a person's "first" name, thus Bibi Katarina. Other titles such as mwalimu 'teacher', mzee 'older person', mama 'mother', baba 'father' are also common, with or without proper names, as respectful ways of addressing the appropriate people. Baba, for example, can be used as a respectful way of addressing a married male, and mama, a married woman. In Tanzania, ndugu, literally 'sibling, relative', is used by many speakers instead of bwana to show political solidarity.

Swahili does not have forms comparable to the definite and indefinite articles in English. Thus, mwalimu can be interpreted as either 'teacher, the teacher, a teacher'. In future lessons we will see there are ways of specifying nouns as definite.

An infinitive in Swahili is formed by prefixing ku- to a verb stem:

ku-fundisha 'to teach/teaching'

ku-soma 'to read/reading'

ku-itika 'to respond/responding'

ku-sema 'to say/saying'

The translation equivalent of the Swahili infinitive is the bare verb with 'to' or, as follows, by a gerund (verbal noun) with -ing':

zoezi la kusoma 'a reading exercise' (literally 'an exercise of/for reading')

kufundisha maamkio 'teaching greetings'

Except for this lesson, verbs will be listed in the vocabularies in their stem form:

-soma 'read/study'

-fundisha 'teach'

-itika 'respond'

In the next several lessons complex verb forms are introduced in the reading selections, thus in this lesson we find:

anafundisha 's/he is teaching' (s/he =she or he)

anasema 's/he is saying/speaking'

wanasema 'they are saying'

The stems in these forms are -fundisha and -sema respectively. The prefixes -a and -wa are pronouns which indicate the subject of the verb. The prefix -na- is a marker which indicates 'present time'. These forms will be studied in greater detail in Lesson 6 (Somo la Sita).

Imperatives are used to give commands and directions. Simple commands, or imperatives, addressed to one person, are formed by using just the verb stem:

Juma, sema,sijambo! 'Juma, say,sijambo!'

Sema tena, tafadhali. 'Repeat, please' or 'Say (it) again, please!'

There are other more complex ways of giving commands in Swahili. An example used in this lesson is