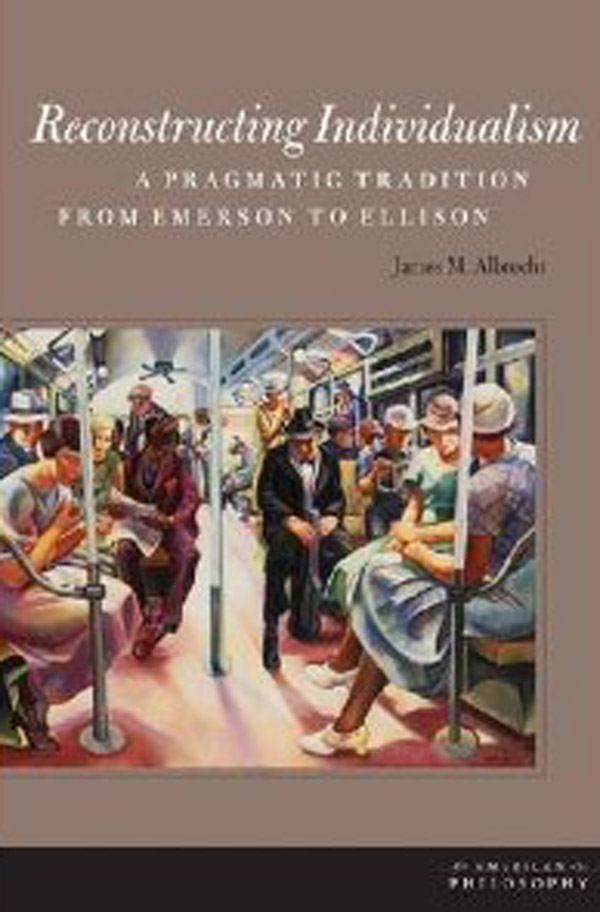

Reconstructing Individualism

American Philosophy

Douglas R. Anderson and Jude Jones, Series Editors

Reconstructing Individualism

A Pragmatic Tradition from Emerson to Ellison

James M. Albrecht

Fordham University Press

New York 2012

Copyright 2012 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Albrecht, James M.

Reconstructing individualism : a pragmatic tradition from Emerson to Ellison / James M. Albrecht.1st ed.

p. cm.(American philosophy)

Summary: Explores the theories of democratic individualism articulated in the works of the American transcendentalist writer Ralph Waldo Emerson, pragmatic philosophers William James and John Dewey, and African-American novelist and essayist Ralph Ellison Provided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8232-4209-2 (hardback)

1. Philosophy, American19th century. 2. Philosophy, American20th century. 3. Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 18031882Philosophy. 4. James, William, 18421910Philosophy. 5. Dewey, John, 18591952Philosophy. 6. Ellison, RalphPhilosophy. 7. Literature and societyUnited States. 8. IndividualismUnited StatesHistory. 9. Individualism in literature. 10. Pragmatism in literature. I. Title.

B832.A345 2012

141'.40973dc23

2011042862

Printed in the United States of America

14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1

First edition

A book in the American Literatures Initiative (ALI), a collaborative publishing project of NYU Press, Fordham University Press, Rutgers University Press, Temple University Press, and the University of Virginia Press. The Initiative is supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For more information, please visit www.americanliteratures.org.

For Lisa;

And for Hannah and Cecily,

Whose arrival in this world taught me the true meaning

of an Emersonian wonder at the advent of a new individual

Contents

There are many persons and a few institutions to whom I owe heart-felt thanks for helping me to finish this work.

First, to friends and colleagues who have read portions of the study and provided both constructive criticism and necessary encouragement: Lisa Marcus, Erin McKenna, Doug Anderson, Joe Thomas, David Robinson, Lawrence Buell, and Michael Lopez. To John Stuhr and Richard Shusterman, who organized a National Endowment for the Humanities summer seminar on American Pragmatism and Culture that immersed me in the works of John Dewey precisely when I needed it most, and to all my fellow participants who made that summer a memorable and sustaining experience. To Al von Frank and Jana Argersinger at ESQ, who first provided me a venue for my work, and to Barry Tharaud at Nineteenth Century Prose. To Helen Tartar and Thomas Lay at Fordham University Press and to Tim Roberts and Edward Batchelder at the American Literatures Initiative, for their expert support in shepherding the book through the editorial and production process. And to all my wonderful colleagues in the Department of English and the Division of the Humanities at Pacific Lutheran University, who provide me with a vibrant community in which to pursue my vocation as teacher and scholar.

Several institutional grants also provided me with invaluable support. The National Endowment for the Humanities funded my participation in the seminar mentioned above; a generous Graves Award in the Humanities funded a semesters research leave that enabled me to write my two chapters on Emerson; and my home institution, Pacific Lutheran, supported me with two Regency Advancement Awards and a sabbatical leave.

Last, I owe a students immense debt to the late Richard Poirier, in whose graduate seminar on pragmatism and American poetry I first became enthralled by the dizzying twists of an Emerson essay. My biggest regret at not having completed this study sooner is that I could not present him a copy with grateful thanks for his being a mentor in the best Emersonian sense.

To Lisa, Hannah, Cecily, and Maggie, I owe inestimable thanks for giving me the kind of loving home that makes work possible and meaningful. And to my parents, James L. and Phyllis Albrecht, I owe thanks for a lifetime of love and support.

Parts of this work have appeared previously in scholarly journals. Portions of chapter 2 appeared in ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance (vol. 41, no. 3; and vol. 45). Chapter 1 appeared in Nineteenth Century Prose (vol. 30, nos. 12); and chapter 6 originally appeared in PMLA (vol. 114). I am grateful to these journals for their permission to reprint my previous work.

Introduction

Toward a Pragmatic Individualism

Individualism is a mature and calm feeling, which disposes each member of the community to sever himself from the mass of his fellows and to draw apart with his family and his friends, so that after he has thus formed a little circle of his own, he willingly leaves society at large to itself. Selfishness originates in blind instinct; individualism proceeds from erroneous judgment more than from depraved feelings; it originates as much in deficiencies of mind as in perversity of heart.

Selfishness blights the germ of all virtue; individualism, at first, only saps the virtues of public life; but in the long run it attacks and destroys all others and is at length absorbed in downright selfishness. Selfishness is a vice as old as the world, which does not belong to one form of society more than to another; individualism is of democratic origin, and it threatens to spread in the same ratio as the equality of condition.

Alexis de Tocqueville

This then is the individualistic view.It means many good things: e.g. Genuine novelty; order being won, paid for; the smaller systems the truer; man [is greater than] home [is greater than] state or church. anti-slavery in all ways; tolerationrespect of others; democracygood systems can always be described in individualistic terms.

William James

Because of the bankruptcy of the older individualism, those who are aware of the break-down often speak and argue as if individualism were itself done and over with. I do not suppose that those who regard socialism and individualism as antithetical really mean that individuality is going to die out or that it is not something intrinsically precious. But in speaking as if the only individualism were the local episode of the last two centuriesthey slur over the chief problemthat of remaking society to serve the growth of a new type of individual.

John Dewey

Individualism has never been tried.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

America has a love-hate relationship with individualism. Many view individualism as morally and politically suspect, as a corrosive force that undermines democracy and is the source of many of our social ills. Such indictments usually focus on two main issues. First, that individualism precludes meaningful political change and is inescapably complicit with the liberal-capitalist status quo. Any ethics that asserts the morality of individualized activity risks being co-opted by the capitalist doctrine that rationalizes the pursuit of individualized wealth as a primaryand perhaps sufficientmeans to the general good. Similarly, through an exaggerated emphasis on individual merit and responsibility, individualism can ignore or minimize social conditions that perpetuate inequalities of wealth and opportunity while, in political terms, engraining a laissez-faire bias against public efforts at reform that might create the conditions for a more widespread individual liberty. If individualism is seen as too complicit with the dominant capitalist beliefs of our culture, it is by the same token distrusted for challenging other opposingand also widely heldbeliefs that equate morality with altruistic self-sacrifice. Such concerns underlie the second major critique of individualism, influentially articulated by Tocqueville: that the equality of social condition and status in modern democracy leads to an increasingly narrow pursuit of self-interest that undermines the fabric of civic life and devolves into a materialistic selfishness. These are serious and fundamental concerns that proponents of democratic individualism must address. Anyone with progressive political leanings who has witnessed a proposed social reformon health care, the environment, or issues of economic justicebecome derailed by outcries against government encroachments on individual liberty would be hard-pressed to deny the force of the first charge. Anyone who has lived in, or observed, the frenetic patterns of work and consumerism in contemporary American society would be hard-pressed to dismiss the claim that a narrowly private and materialistic individualism exacerbates social isolation and fragmentation.

Next page