The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Most of this book is based on interviews I conducted in Central Florida from 2016 through 2020. The interviewees who spoke to me in an official or business capacity are typically referred to by their last names. Most of the others, especially those whom I spent more time with and got to know personally, are referred to by their first names. In some cases, I have changed the names of businesses and people quoted in these pages to protect their identities.

In Florida, the term most often used to refer to people of Latin American descent is Hispanic, so I have followed that usage in this book. Likewise, while I occasionally speak of people who are unhoused or unsheltered, I mainly use the term homeless, since that is how most people living on the streets and in the woods (and even many of those living in motels) refer to themselves.

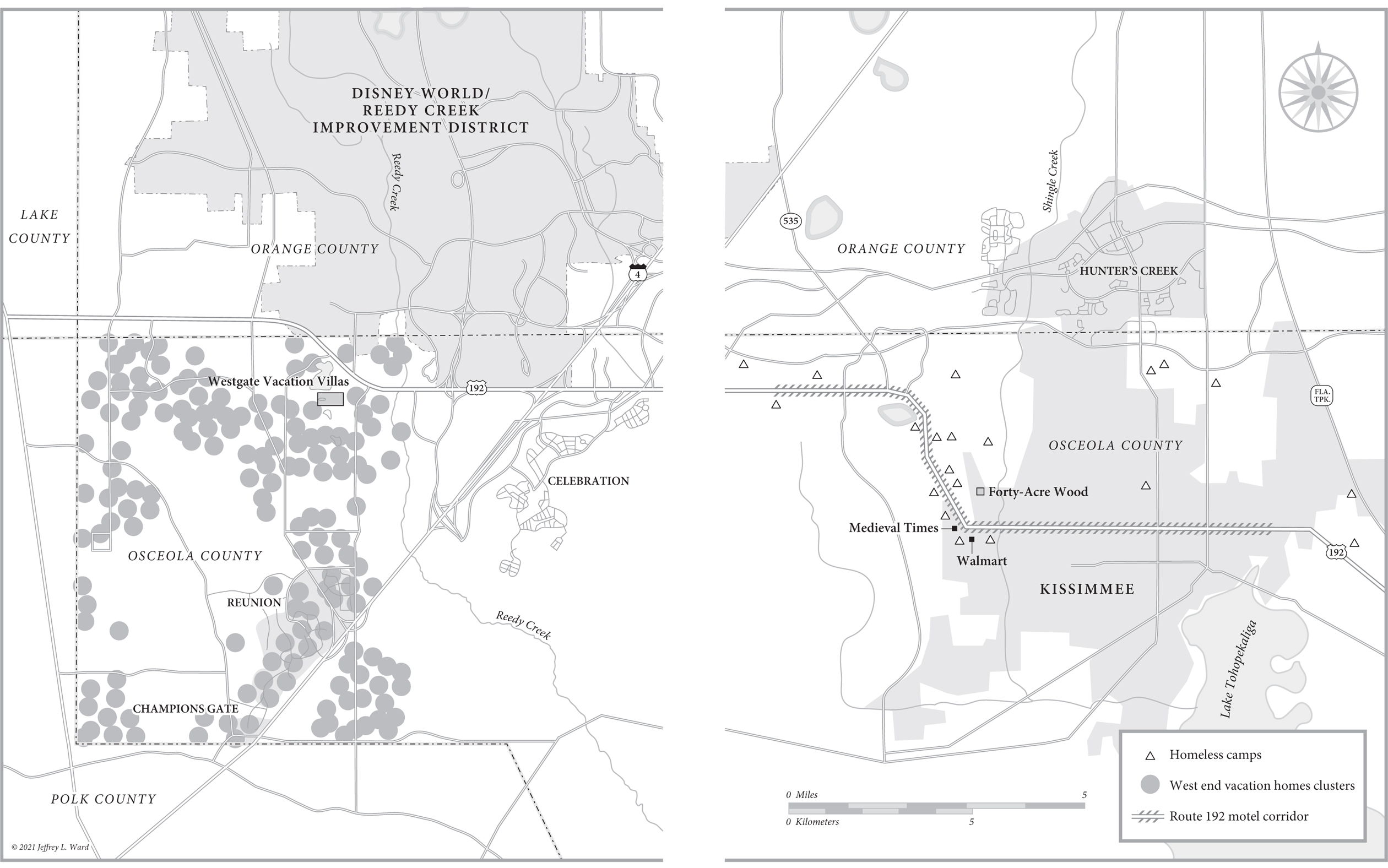

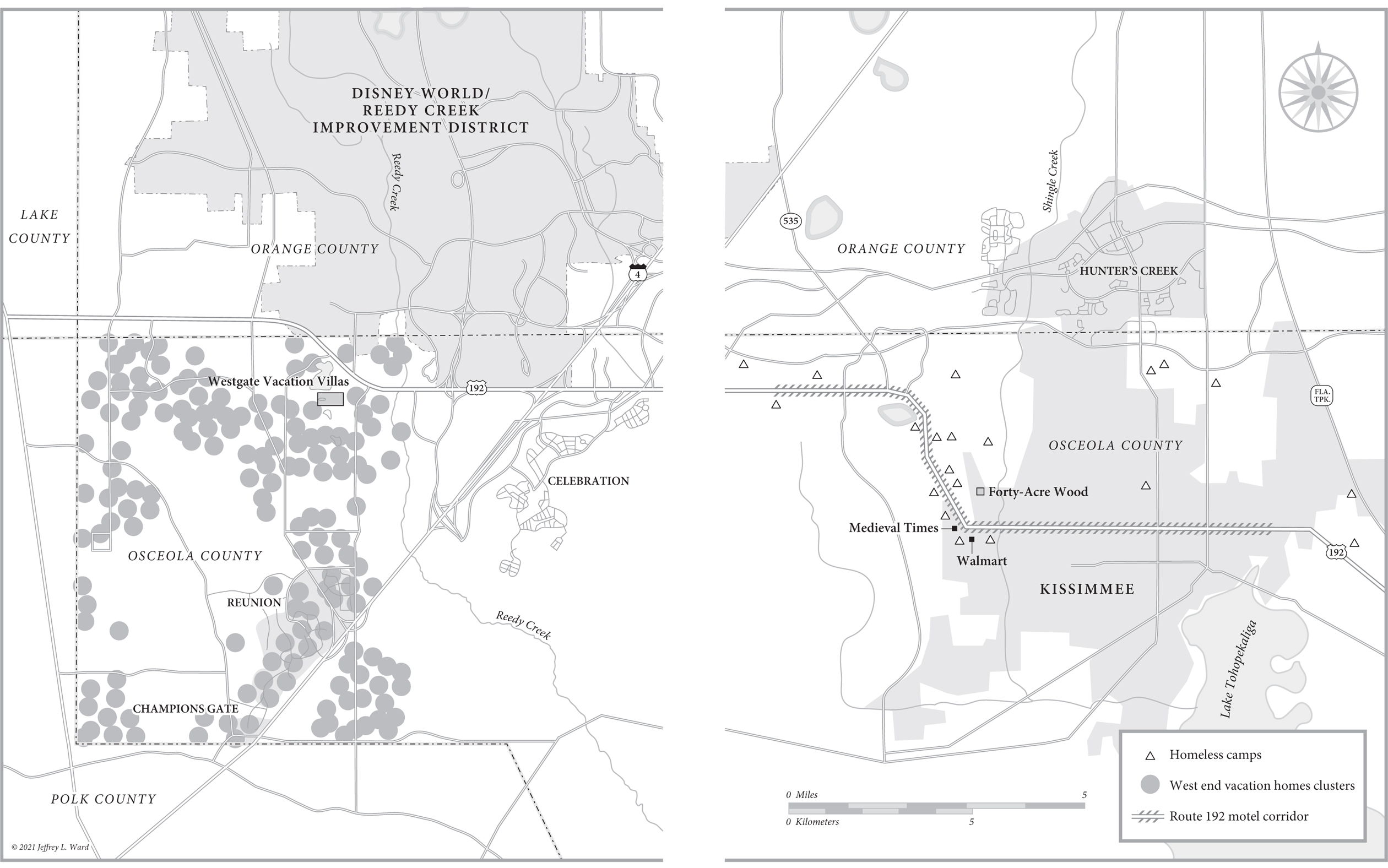

C ELEBRATION S MAIN STREET is tailor-made for a Fourth of July parade. A redbrick road terminating in a dainty lakefront esplanade, lined with colonnaded storefronts topped by white balconies, it is a compact showpiece for small-town America, the perfect stage set for spectacles like this one. Kissimmee, the seat of Osceola County, fifteen miles to the east, has its share of old-town charm, but it cannot compete, and with its rapidly shifting demographic is more likely these days to attract a crowd for its annual Puerto Rican Day parade in September. Indeed, in 2019, I noticed that Kissimmees mayor, Jose Alvarez, chose to march in Celebration on the Fourth of Julythough the decision was no doubt swayed by the prospect of votes for his upcoming bid to be an Osceola County commissioner. The towns military veterans and Daughters of the American Revolution led the parade, but the biggest crowd pleaser was a Star Wars float flanked by Stormtroopersa reminder that Galaxys Edge, a massive Star Warsthemed attraction, was set to open in Disney World in just a few weeks.

Twenty-one years earlier, the Independence Day parade had been my swan song for a year spent in an apartment at the epicenter of this much-scrutinized town in Central Florida. I had come to write a book, The Celebration Chronicles, about the trials and tribulations of its pioneer residents. Back then, in Celebrations fledgling years, the parade was more of an improvised affair, and I was cajoled by neighbors into playing the role of George Washington at the head of the procession. They also made me promise to return to Celebration, but only when it had grown up. Like children, new towns surely have the right to mature before their character is judged.

I kept my promise. A quarter century after Disney sculpted this New Urbanist experiment out of Central Floridas scrub and swamp and launched a thousand newspaper articles about the audacity (or folly) of building a planned utopia, I found that Celebration has some new lessons to teach us. But to see why, you had to lift your gaze above street level, to the upper floors of the downtown buildings. There, above the cheering throngs with their starred-and-striped socks and bandannas, were telltale signs of neglect and disrepair: patched and stained walls, rotting columns, bubbling stucco, broken tiles, cracked gutters. Many of the pastel surfaces were covered in layers of grime. And the distress signs on the exterior were nothing compared to the damage on the inside. The condo residents in these buildings have horror stories to tell about the ruination of their units: water intrusion that takes the form of small waterfalls during a storm, blooms of mold growth, vast termite colonies, sagging floors, and wobbly stairways.

In a town where aesthetics reign supreme, these centerpiece buildings had been designed with a deliberately dated, prewar look in mind, but they were meant to appear as if they had been carefully preserved through decades of weathering. Without real maintenance, of course, the look failed. Floridas climate can be unforgiving to wooden buildings, especially those faced with stucco, and most homeowners should know that diligent upkeep is required to stave off rot and decay. In this most iconic of places, someone was clearly falling down on the job. If this had been a Disney fairy-tale melodrama, the blight would be the result of a spell cast by some fiendish impostor, while the return of the rightful royal owner would restore health and vitality to all. But who was the culprit here, and what were the prospects for a happy ending?

Unlike almost anywhere else, Celebrations downtown did not grow organically along with the rest of the community. Its tidy retail core, with rental apartments perched on top of the stores (Osceolas first mixed-use arrangement in decades), was hastily erected in the mid-1990s, in advance of the arrival of residents. Disneys deep pockets allowed it to initially subsidize the carefully chosen retailers so that they could flout the standard rules of commercial development and open their businesses to visitors long before the towns population could support any of them. Without doubt, some of the blame for the current grunginess of these buildings is a consequence of that rush job, or what residents used to refer to as Mickey Mouse constructionthat is, maximum focus on the facade and minimal attention to what lies behind it. And it was no surprise when other, wholly residential sections of the town also saw their share of construction flaws, as builders with undertrained work crews scrambled to meet the ravenous market demand for a Celebration address.

But expedited building with slipshod results is hardly unusual in Floridas real estate landscape, where entire subdivisions often sprout overnight, carved out of cow pasture. Nor is the problem wholly a legacy of Celebrations original construction. It is also the upshot of Disneys reckless 2004 sale of the entire downtown complex to a private equity investor who had no record of managing town centers nor any vested interest in keeping up the high maintenance standards set by the brand-conscious developer. From his Madison Avenue office, a thousand miles away, he followed the Wall Street playbook of squeezing revenue from his new asset by hiking rents, selling off land parcels for condo development, and refinancing his loans in order to drain off equity for his investors. Hardly any of the proceeds went back into the upkeep of the buildings, and the value of the downtown units plummeted.

The full scope of this trauma, and the dogged efforts of a group of downtown condo owners to fight it, became clear during my regular visits over the next few years. But I also quickly learned that housing distress was by no means confined to the upmarket precincts of Celebration. Variants of this affliction had spread all across working-class Osceola County, soon to be pinpointed as the place with the least amount of affordable low-income housing per capita in the entire United States. And they were equally familiar to tenants and homeowners struggling with housing security throughout the country.