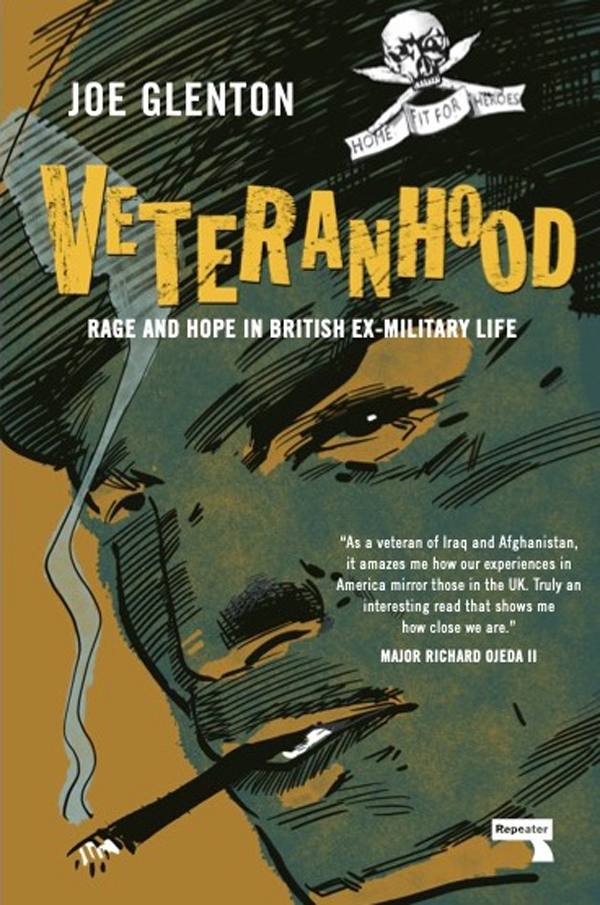

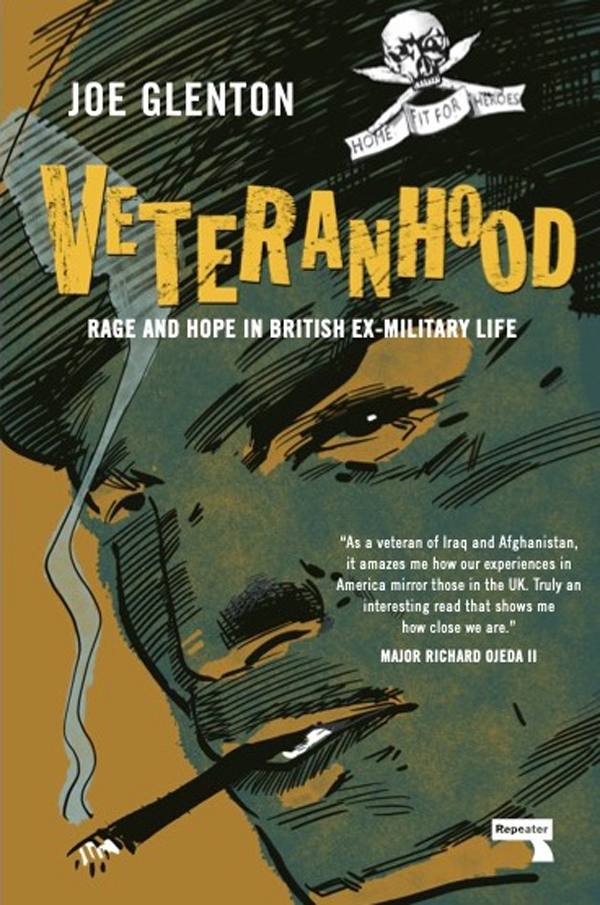

Veteranhood is a book Ive been waiting for for years, and I now realise only Joe Glenton could have written it. A groundbreaking and essential correction to the media fairytale of life as a UK military vet, written in the style of the legendary Gonzo writers of the 1960s. Its Andy McNab meets Hunter S. Thompson and does that rare thing: provides deep insight while treating the reader with electrifying prose. I read it in one sitting.

MATT KENNARD, CO-FOUNDER OF DECLASSIFIED UK

Glentons superb and angry memoir of comradeship and resistance takes you where no sane person would want to go: to the frontline of combat with people who understand how shit war is, and are coming back mad as hell.

PAUL MASON, AUTHOR OF POSTCAPITALISM: A GUIDE TO OUR FUTURE

The reality of military life, the failed wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the fate of the ex-military is finally laid bare. Funny, sad, hard-hitting... an instant classic.

PAT MILLS, CREATOR OF CHARLIES WAR

As a veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan, it amazes me how our experiences in America mirror those in the UK. Regardless of the decisions made by governments, dog-faced soldiers that spend their days in the enemys backyard all share the same experiences during and after the war. Truly an interesting read that shows me how close we are.

RICHARD OJEDA II, MAJOR, US ARMY (RETIRED) AND FORMER DEMOCRATIC SENATOR FOR WEST VIRGINIA

Published by Repeater Books

An imprint of Watkins Media Ltd

Unit 11 Shepperton House

89-93 Shepperton Road

London

N1 3DF

United Kingdom

www.repeaterbooks.com

A Repeater Books paperback original 2021

Distributed in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York.

Copyright Joe Glenton 2021

Joe Glenton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

ISBN: 9781913462451

Ebook ISBN: 9781913462550

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed and bound in the UK by TJ Books

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Two men have appeared in front of me. They are in hot blood, tails up, looking for confrontation. One is small and gnarled. One is younger, bigger, a tattoo up his neck. Probably King Billy riding a poppy. It is autumn and I am in Loyalist Belfast, where every day is Remembrance Day. Gnarled gestures over his shoulder to the dank boozer he has appeared from.

Are you filming the pub? (You sounds like yoy in these parts.)

I point up at the Union Jacks, Parachute Regiment flags and RAF roundels fluttering over Sandy Row. The adrenalised arsehole, soldiers say, flutters rapidly between the diameter of a 5p and a 50p. I am around about there.

The flags, lads.

Why are you filming the flags?

Were making a film.

My German cameraman is filming nearby, oblivious to the fact we are both about to get kneecapped by the UVF. Documentary team missing. Remains found in some minging peat bog. All we had wanted was footage of flags in a corner of the world where everything, as it turned out, had flags hanging off it. There, on the cusp of abduction, it seemed like a good time to play The Worlds Most Grating Card.

Its about veterans, lads. Im a veteran myself.

Brazen, but the veteran-signalling lands. They do not even press the question; they just accept it.

Do I look that veteran-ish?

Oh aye, crack on then.

Smiles all around. Neck Tattoo shakes my hand, and they go back to their pints. My kneecaps live to creak on, another legacy of my army days. Of course, it is perfectly possible they were in no way connected to a paramilitary, just locals guarding their corner of a tough town. But that is the kind of doom scenario which flashes through your head sometimes in a nose-to-nose like that. At least I kept my flapping internal, just like the Mob (the army) taught me.

About six months later I sit facing twenty young Afghans in a freezing room in Kabul. We have spent the week riding around the Badlands in a Toyota Corolla. Nearly fifteen years after I came here as a soldier, I made it out onto that fabled place we call the ground, outside the wire of a military base. Unarmed and with no air support, we travelled dressed as Afghans; careening around in Kidnap Central in the Corolla, occasionally in an Afghan National Police Humvee. We were hunting CIA death squads called Zero Units, speaking to their victims and, on one occasion, getting lost in Taliban territory. It had turned out that, fifteen years on, the US and British-trained ANP were still cowboys.

Yet somehow, in the quiet moment when the hardest work had been done, the young Afghan peace activist sitting opposite me seems more intimidating than the IEDs, the cliff-edge roads or, according to the Trump-backing and anal-fixated ex-SAS soldier who had run our hostile environment course back in the UK, the unwavering certainty of being bummed if captured.

The activist asks Mr Joe how many Afghans he killed when he was a soldier.

Always that question

South London. Numb-faced at a house party. Line upon line racked up on a table nearby. It is that time of night where in this non-smoking house we are all smoking in the kitchen. A group of Italian goths are dancing weirdly on the tiles nearby. A person of unserious politics functionally liberal, performatively left-wing has announced to me that people join the Mob because they are racists, because they want to kill. The drugs have cooled my blood so, rather uncharacteristically, I try to explain the complex drivers of military enlistment rather than just tuning this latest ignoramus in like a crackling radio.

I could go on. Incidents like these have been racking up for some time. The fact is that, like any group of people, veterans are a vessel into which people pour assumptions and half-truths.

The historian Gwyn A. Williams once said that the past is chaos and to make sense of that chaos we must put questions to it. History is breach after breach, crisis after crisis. For Williams a communist, Welsh nationalist and Normandy veteran what those questions will be is dictated by who is doing the asking. It follows that bankers and miners, men and women, soldiers and civilians would make different enquiries. Despite the carefully curated appearance of order, the military and the military experience are nothing if not chaos, and those of us who pass through them must formulate and ask our own questions. If I were to interrogate just these few moments of my post-military life, I could ask: Why do Afghan kids assume I have killed multiple people? Why did that melt think homicidal tendencies are a prerequisite for military service? And why do swaggering Loyalists think I am a good bloke?

Next page