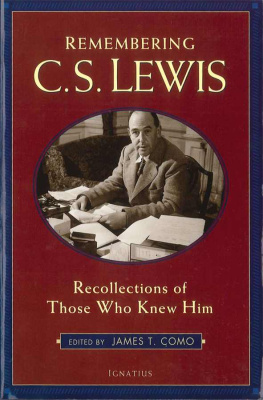

REMEMBERING C. S. LEWIS

REMEMBERING C. S. LEWIS

Recollections of Those Who Knew Him

EDITED BY

JAMES T. COMO

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

This book is the Third Edition of the work previously titled

C. S. Lewis at the Breakfast Table and Other Reminiscences

Reprinted by permission of James T. Como

Original edition published in 1979 by Macmillan, New York

Second edition published in 1992 by Harcourt Brace and Company,

London and New York

All previously unpublished writings of C. S. Lewis,

Bibliography of the Writings of C. S. Lewis and

Alphabetical Index of the Writings of C. S. Lewis

copyright 1979 by C. S. Lewis Pte Ltd.

Supplement to Bibliography copyright 1992

by C. S. Lewis Pte Ltd.

Some of the pieces in this volume previously appeared in

CSL: The Bulletin of the New York C. S. Lewis Society,

The Brink of Mystery, Anthroposophical Quarterly, New Blackfriars,

Unicorn , and Encounter . Complete citations may be found in the

list of contributors.

Excerpt on page 19 from The Mystery of Language

from The Message in the Bottle by Walker Percy.

Copyright 1975 by Walker Percy. Reprinted by permission of

Farrar Straus and Giroux.

Cover art: Photograph of C. S. Lewis by Arthur Strong

Cover design by Riz Boncan Morsella

2005, 1992, 1979 by James T. Como

All rights reserved

This edition printed in 2005 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

ISBN 978-1-58617-108-7

ISBN 1-58617-108-9

Library of Congress Control Number 2005926537

Printed in the United States of America

To all who would have thanked C. S. Lewis but could not, and to the rational opposition of goodwill.

And (if an editor may yet) to my wife, Alejandra .

CONTENTS

James T. Como

PART ONE: Earliest Perspectives

Leo Baker

Alan Bede Griffiths , O.S.B.

A. C. Harwood

PART TWO: Master

Erik Routley

Luke Rigby , O.S.B.

Derek Brewer

John Wain

Peter Bayley

PART THREE: Colleague

Adam Fox

Gervase Mathew , O.P.

Richard W. Ladborough

PART FOUR: Transatlantic Ties

Charles Wrong

Jane Douglass

Nathan C. Starr

Eugene McGovern

PART FIVE: Much More Than a Tutor

Walter Hooper

Charles Gilmore

Clifford Morris

George Sayer

Roger Lancelyn Green

Robert E. Havard

James Dundas-Grant

PART SIX: The Essence That Prevails

A. C. Harwood

Austin Farrer

Walter Hooper

PREFACE

We may reasonably expect that C. S. Lewis will soon become an established figure: that is, his literary impact will be recognized by scholars and teachers to such an extent that its importance shall be quite taken for granted, and he will be typed, so that people who know little will assume much. Given Lewiss stance as a polemicist, this development is noteworthy because chinks in personal armor are often exploited as though they were weaknesses in argument.

Indeed, we may already see the beginnings of such a pattern. I recently read that Lewis, because of his antagonism toward Americans, turned down an invitation to speak in America by writing a nasty refusal on a piece of toilet paper; but the incident never happened, and Lewis is not on record as possessed of an antagonism toward Americans. In a somewhat different vein, a reviewer for the New York Times has written that Carlos Castaedas peyote-cult best-sellers may be derived from

George MacDonalds pro-Christian fantasies.... MacDonalds Phantasies and Lilith were reprinted in 1964 with an introduction by C. S. Lewis. MacDonald and his student... wrote their fantasies in the pregenital stage, disguised in C. S. Lewiss case as Christian morality, a disguise, which Wilhelm Reich would say is transparent. C. S. Lewis is just as afraid of genitality as Castaeda, and toward the end of his life C. S. Lewiss profound hatred of women began to come out in his short stories.

To be sure, this detritus of incantatory devil-terms exemplifies only one extreme branch of the scientism that Lewis and others have made easy work of; and, on the other hand, admirers of Lewis have often indulged a cultism of their own (overlooking, for example, the ambiguities of Lewiss late marriage and even wanting to cover up his brothers alcoholism). So evidently we are witness to the start of that inevitable process that turns public figures into celebrities, people, according to Daniel Boorstin, who are famous for being well known.

It would seem, then, that the time has come for the establishing of reliable perceptions, substantive impressions of people directly knowledgeable of, and sensitive to, the shadings of this striking personality. This book is not a biography. The recollections in it are often ruminative, even speculative; rarely do they argue a thesis, and the style throughout is nonscholarly. Most of the essays were written expressly for this volume, and only Professor Wains has had a prior readership of as many as several hundred. The singular authority of this collection derives from one central fact: all but two contributors (Eugene McGovern and I) were personally acquainted with C. S. Lewis.

On the belief that the sort of response elicited by a person is itself evidence of the sort of person he was, I have kept editorial intrusion to an absolute minimum. It is for the alert reader to note, to ponder, and perhaps to reconcile conflicting impressions among the contributors or between what is said here and prior impressions of Lewis, for the book comprises a great many perspectives. The length of time and the stage of life during which Lewis was known, the degree of intimacy to which he was known, the angle of friendship that was shared, and the depth of familiarity with his workall these vary widely among the contributors.

Thus, the informal Lewis admirer may be startled to read that Lewis did not much indulge in wit, that he evidenced outbursts of hatred, and that he did not talk frequently of his military experience; but that reader should note that this Lewis was an abundantly posturing atheist in his early-to-mid-twenties. Did Miss Anscombe wipe the floor with Lewis on the occasion of their epic confrontation at the Socratic Club? Opinions differ, and so must answers, depending upon whether one inquires after dramatic impact or soundness of argument. In the realm not of fact but of inference the knowledgeable reader might be tempted to demur, at times, from the opinion of a contributor. Did Lewis overreact to the idea of a personal God? Did he maintain that poetry has nothing to do with the poets feelings or, rather, that our judgment of poetry ought to be independent of our knowledge of the poets personal life?

Most Lewis admirers can wait for the obligatory uniform edition and Guide to the Works of, and to ensure that he does not become merely a figure they should welcome such questionstheir number and complexityas those just given. But if Lewiss response to sexuality, for example, is not irrelevant to our interest in him and in his work (though it is, I suspect, far less relevant than our modern temper takes it to be), then impressions of that response ought to be fitted into a comprehensive frame of reference as variegated and as subtle as the person it purports to accommodate. The danger is that we will build into this frame, or impose upon it, assumptions and expectations alien to its subject; that is the sort of partisan or anti-intellectual dogmatism that this booknot systematic or synopticis intended to allay. As with most of Lewiss own books, as with the Green and Hooper Biography , as with Light on C. S. Lewis (edited by Jocelyn Gibb), this book attempts to allow the reader not so much to study Lewis as to meet him; the appropriate verb, as Lewis might have put it, would be not savoir but connatre .

Next page

![Beverly M Lewis] - The Beverly Lewis Amish Heritage Cookbook](/uploads/posts/book/96304/thumbs/beverly-m-lewis-the-beverly-lewis-amish-heritage.jpg)