Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4875-0266-9 (cloth)

1. Oranges Social aspects Italy History. I. Title.

This book has been published with the assistance of the University of Vermont, in particular the College of Arts and Sciences and the Department of Romance Languages and Linguistics.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario.

Acknowledgments

Despite having a climate inhospitable to the growth of citrus fruit, the town of Burlington in Vermont has been a wonderful place in which to spend my adult life, and the University of Vermont a nurturing home for my academic career. In this era, especially, when the value of the humanities often goes unappreciated, I have been fortunate to receive the steady support of administrators, colleagues, staff, and students alike. Professional development funds have allowed me to visit libraries such as the Huntington Library in California and the Biblioteca Corsiniana in Rome, and to be inspired by contact with old volumes. Though my gratitude for the existence of Google Books knows no bounds, working on a screen does not produce the same results as reading, touching, and even smelling books on which others have also worked for centuries before me. A recent sabbatical gave me the time and the space to complete the first full draft of this book; and the funds from the Deans Office of the College of Arts and Sciences, ably headed by Bill Falls, and from the Department of Romance Languages and Linguistics, with my friend and colleague Joseph Acquisto at the helm, have helped with publishing subventions and general encouragement.

Mark Thompson at the University of Toronto Press has been an enthusiastic and helpful supporter from the moment I first contacted him about this project. The two anonymous readers whom he carefully selected gave me precious advice where would we be without the generosity of strangers? and my book is so much better for their thoughtful input. Many others have given me help along the way. My friend Francesca Guarnieri brought to my attention the orange-peeling scene in Brusatis Bread and Chocolate, with which I begin the introduction. Stephanie Heimgartner kindly invited me to give a keynote address at her 2015 conference on pregnancy in literature (Bochum, Germany), which impelled me to delve deeper into Ferraris representation of pregnant citrus fruit.

Early versions of portions of this book have appeared in other venues, and although the book has undergone extensive revisions, I want to acknowledge the following: How to Candy Oranges and Reprimand the Pope: Catherine of Sienas Letter 346 to Urban VI, Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality 16.1 (2016), 4157; The Fruit of Love in Giambattista Basiles The Three Citrons, Marvels & Tales: Journal of Fairy Tale Studies 29.2 ( 2015 by Wayne State University Press, with the permission of Wayne State University Press); and Of Blood Oranges and Golden Fruit: A Sacred Context for the Facts of Rosarno, California Italian Studies 5.1 (2014).

Unless otherwise noted, all translations throughout this book are mine. For helping me translate Ferraris complicated Latin in his Hesperides, and for so much of what makes me happy in this life, I am joyfully indebted to my husband, John Cirignano.

I do not remember how I learned to peel citrus fruit in the Italian way (a description of this process may be found in my introduction), but I do have clear memories of my mother, Stefania, peeling mounds of oranges for her husband and six children after dinner; I am grateful to her for passing on this skill, a short chapter in my long list of debts to her. John, Paul, Gemma, and Sophia Cirignano have been the eager and grateful recipients of peeled oranges for many years now; without their enthusiastic eating I would not be so proficient at this art or, without their lively and constant presence, at the far more important art of loving.

My own attempts to teach Americans how to peel oranges like an Italian does have mostly failed. The one hope is my youngest child, Sophia; in this, as in many other aspects of her life, she knows that the secret is to apply just the right amount of pressure. It is to her that I dedicate this book.

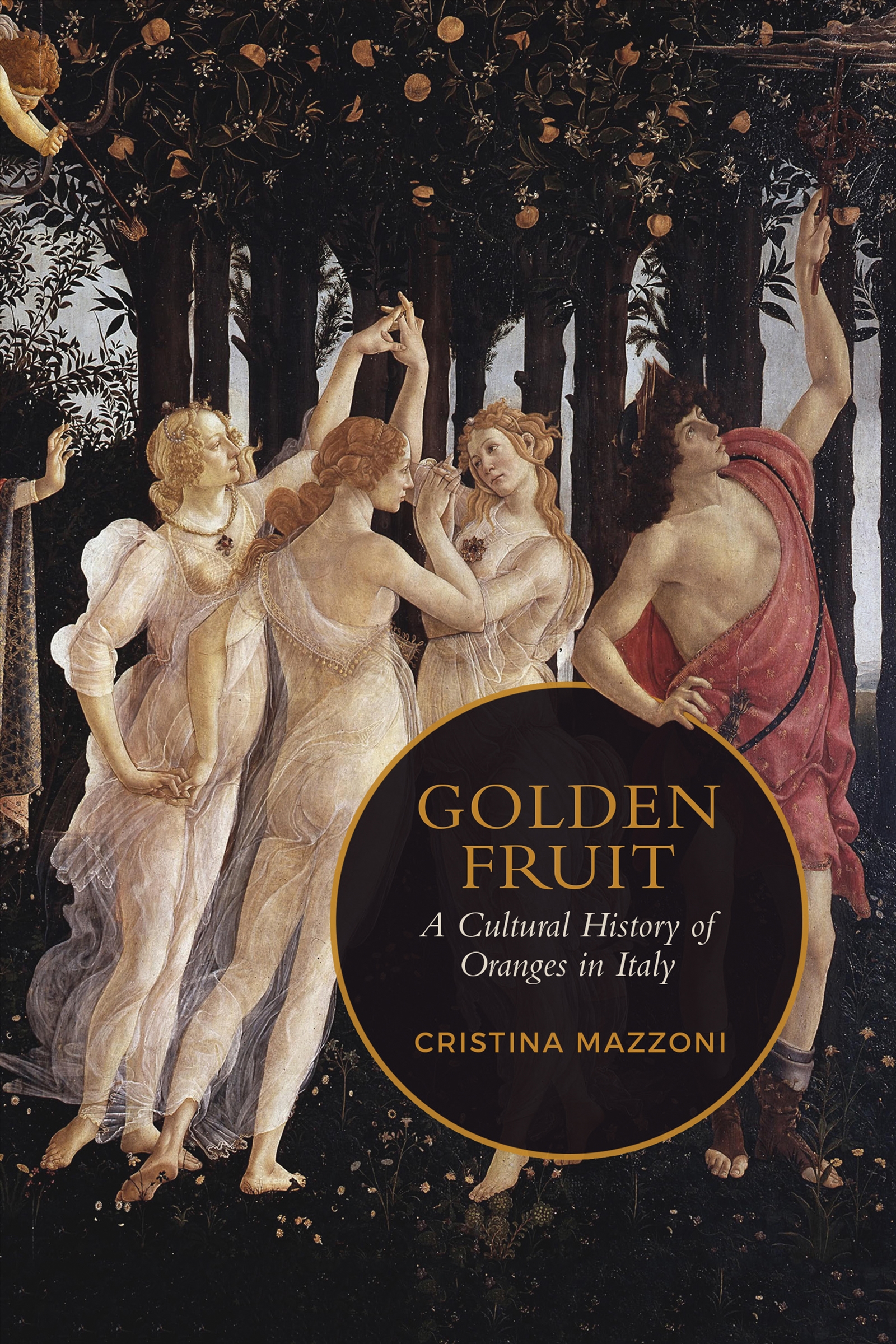

GOLDEN FRUIT

A Cultural History of Oranges in Italy

Introduction

How to Peel an Orange

In Franco Brusatis film Bread and Chocolate (Pane e cioccolata, 1974) the beloved Roman actor Nino Manfredi plays an Italian immigrant to Switzerland who has taken a job as a waiter at an upscale restaurant. When a stodgy, German-speaking diner distractedly orders an orange, Nino visibly panics, and film viewers know very well why: serving an orange in this particular establishment requires peeling it by means of an elegant and complicated procedure that Nino has not yet mastered. The technique involves the deft use of fork and knife, and viewers of the movie have already observed another waiter effortlessly perform it over a porcelain plate, through Ninos daunted eyes. Spellbound, Nino had observed the artistic results of his colleagues efforts the various sections of the orange peeling magically open up like a blooming flower at the end of the waiters scoring tour de force. When he tried to imitate this artistry, the orange flew off the plate and onto the restaurant floor. Nino tries to change the mind of the German-speaking customer about what fruit he might prefer by offering him strawberries. He does this in Italian, however, a language that the snobbish customer does not know or seem interested in understanding. These attempts to change the customers language and fruit preference fail. Nino then asks to be excused for a minute, goes to the back of the restaurant, and, under the wide-open eyes of a flabbergasted Swiss cashier, roughly peels the orange with his teeth by biting off and spitting out one chunk of rind at a time, including the stem, hastily facilitating his dental performance with the work of his fingers. Nino then places the now-peeled fruit inside the perfect flower-shaped peel that has been prepared by his co-worker and discarded by a previous customer a paragon of Italian ingenuity and a personification of the resourcefulness so often born of necessity. In the words of a critic, Nino is generous, inventive and creative, as we see in the restaurant scenes, when he borrows a perfect orange peel from a more skilled colleague (Cavallaro 27).