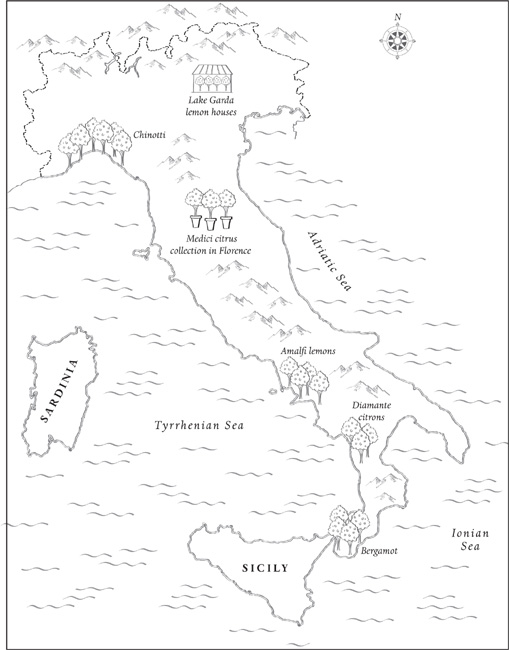

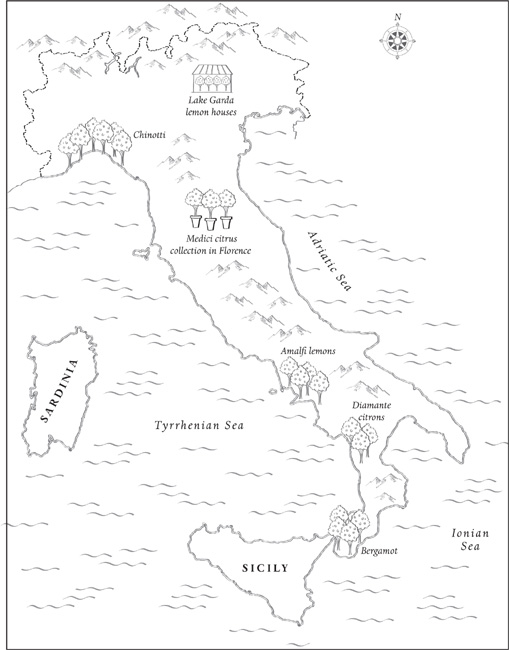

The Land Where Lemons Grow

The Story of Italy and Its Citrus Fruit

HELENA ATTLEE

Published by The Countryman Press,

P.O. Box 748,

Woodstock, VT 05091

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, NY 10110

First published in Great Britain by Particular Books 2014

U.S. edition published by Countryman Press 2014

Copyright Helena Attlee, 2014

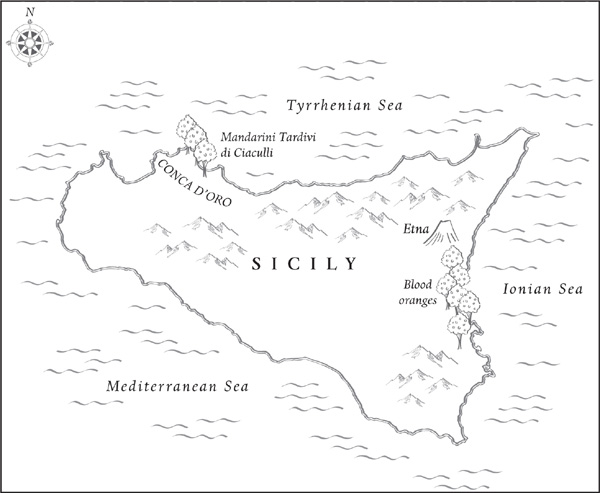

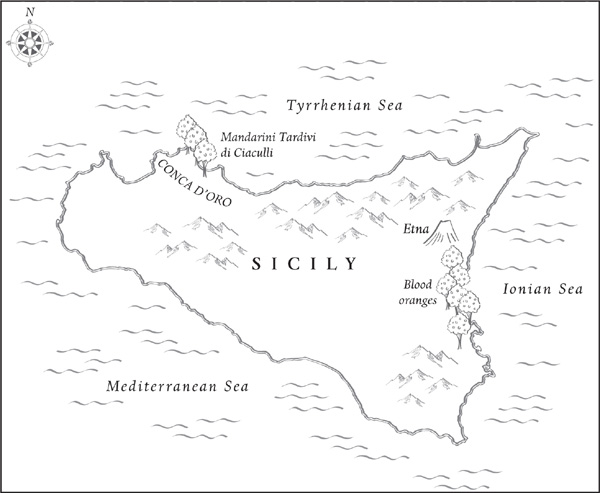

Maps copyright Jeff Edwards

Endpapers akg-images/Franois Gunet

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Ail rights reserved Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval System, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanicaL photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data are available.

The Land Where Lemons Grow

ISBN: 978-1-581-57290-2

ISBN: 978-1-581-57610-8 (e-book)

For Alex, of course

Contents

I began to gather material for this book long before I knew I would write it, and my thanks must go to all the citrus farmers, nurserymen and gardeners who have been so generously conversational over the years. I am especially grateful to Marco Aceto in Amalfi, Salvino Bonaccorso, Princess Maria Carla Borghese and Giuseppe Messina in Sicily, Paolo Galeotti, Gionata Giacomelli and Ivo Matteucci in Tuscany, Giuseppe Gandossi and Domenico Fava on Lake Garda, Pietro Donato, Antonio Miceli and his daughter Sara in Calabria and Danilo Pollero in Liguria.

I am much indebted to Professor Giuseppe Barbera for his kindness and enthusiasm, and for sharing his extensive knowledge of the political and economic history of citrus in Sicily, John Dickie for valuable insights into Mafia history, to Dr Chiara Nepi at the Natural History Museum in Florence and also to Stena Patern, Giorgio Galletti, Ezio Pizzi, Vittorio Caminiti, Franco Galiano and Schmuel Keller. My thanks to Dr Cathie Martin of the John Innes Centre in Norwich and Professor Paolo Rapisarda of CRA-ACM in Sicily for generously sharing their research, and to Dr Justin Goodrich of Edinburgh University for patiently answering botanical questions.

I have travelled all over Italy in pursuit of citrus, journeys that would have been impossible without the kindness and hospitality of many people, including Margherita Bianca, Rudolf and Benedikta von Freyberg, Rachel Lamb, Marchese Giuseppe and his daughter Giulia Patern Castello di San Giuliano and Cristina di Martino in Sicily, Lucia Rossi in Ivrea and Nick Dakin-Elliot in Tuscany.

As ever, I am grateful to my dear friends Valeria Grilli in Rome and Jenny Condie in Venice, whose enthusiasm and practical help have been essential at many stages of my research, to Alex Dufort for kindly testing the recipes in the book, to Sue MacDonald and Boxwood Tours for support in so many ways, and to Natoora (London) for generously supplying the fruit used for recipe testing.

My thanks also go to Anthony Ossa Richardson for his translations of Giovanni Battista Ferraris Hesperides and to my agent, Antony Topping, of Greene and Heaton for good advice, humour and unstinting support. Thanks to all at Penguin, and in particular to my editor, Helen Conford, for her enthusiastic and incisive input.

Above all, thank you to Alex Ramsay and our three daughters for years of encouragement, and for their patience during my long absences, both in Italy and at my desk.

Citrus Crops in Sicily

The Land Where Lemons Grow

I remember when planes were so expensive that people usually made the long journey from England to Italy by ferry and train. Once you got to Paris it was easy because you could catch the Palatino, a sleeper that sped you through the night towards Florence and Rome. I first made that journey over thirty-five years ago. At dawn I lifted a corner of the curtain in the stuffy couchette and realized we had already crossed the border. We were somewhere near Ventimiglia on the Italian Riviera, and there were lemons growing beside the station platform, their dark leaves and bright fruit set against a backdrop of nothing but sea. I never forgot those trees, or the way they charged the landscape around them, making it seem intensely foreign to my very English eye.

I didnt know it then, but travellers from northern Europe have always been thrilled by the sight of Italian citrus trees, and so my reaction was entirely predictable. Hans Christian Andersen, the Danish author and poet best known for his fairy tales, visited Italy in 1833, and when he saw citrus groves for the first time he responded with the mixture of rapture and envy that Italy can still provoke among visitors from colder and less romantic countries. Just im agine the beautiful ocean and entire forests with oranges and lemons, he wrote to a friend; the ground was covered with them; mignonettes and gillyflowers grew like weeds. My God, my God! How unfairly we are treated in the north; here, here is Paradise.

A few years after my first glimpse of lemons I returned to Italy as a student. I had chosen to live in Siena, and although Tuscan winters are much too harsh for citrus trees to grow outside all year, I got used to glimpsing pots of lemons in the sunny courtyards of city palaces and on terraces in front of country villas. When they disappeared from sight in winter I learned they had been taken into the shelter of purpose-built lemon houses, or limonaie. At first I assumed that Italians took their citrus trees for granted, rather as we do our apples in England. As my Italian improved, however, I began to realize that the trees and their fruit had a special place in the Italian imagination. When Galileo wrote Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, the book that would lead to his conviction for heresy in 1632, he used oranges to illustrate the absurdity of the different values we give to the objects around us. What greater stupidity can be imagined than calling jewels, silver and gold precious and soil and earth base? he wrote. People who do this ought to remember that if there were as great a scarcity of soil as of jewels or precious metals, there wouldnt be a prince who would not spend

For many years my working life has been rooted in the elite world of Italys gardens, both as a writer and as the leader of garden tours. This has made it easy to pursue the history of citrus as an ornamental garden tree, and yet as my interest grew, I realized that those pot-grown trees represented only a fragment of the whole story. During journeys that have taken me from the bergamot groves of Calabria, on the southern tip of the Italian peninsula, to lemon houses set against the snowy backdrop of the Alps, I found that citrus trees and their fruit have had a radical part to play in Italys political and social history, and have brought extraordinary wealth to some of the poorest places in the country. Unlike those cosseted garden specimens, these trees grew in open ground, and like the oranges known as wu nu, or wooden slaves, in ancient China, they worked tirelessly to make and keep their families rich.