Guide

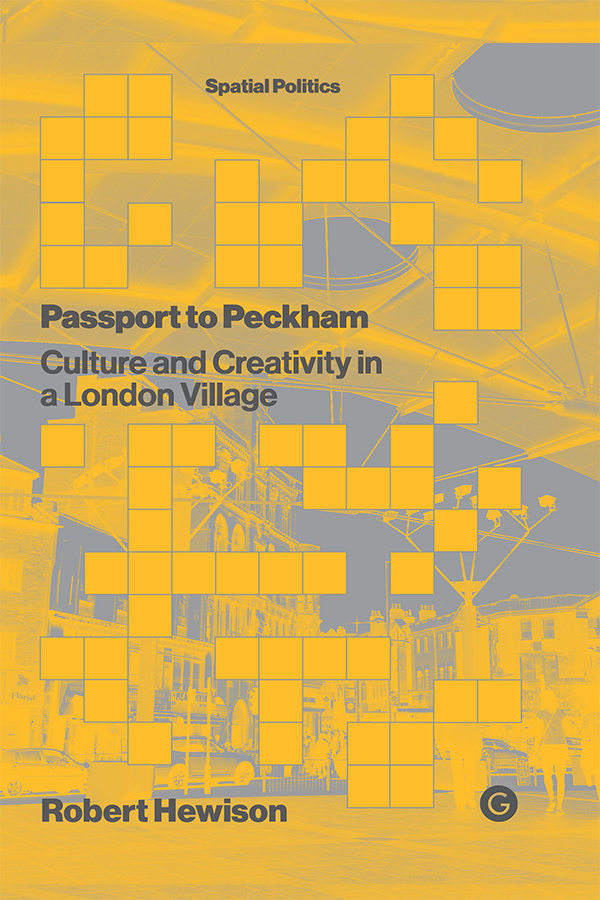

Passport to Peckham

BY THE SAME AUTHOR:

Under Siege: Literary Life in London, 193945 (1977)

In Anger: Culture in the Cold War, 194560 (1981)

Too Much: Art and Society in the Sixties, 196075 (1986)

The Heritage Industry: Britain in a Climate of Decline (1987)

Future Tense: A New Art for the Nineties (1990)

Culture and Consensus: England, Art and Politics since 1940 (1995)

Cultural Capital: The Rise and Fall of Creative Britain (2015)

Passport to Peckham

Culture and Creativity in a London Village

Robert Hewison

Copyright 2022 Goldsmiths Press

First published in 2022 by Goldsmiths Press

Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross

London SE14 6NW

Printed and bound by Versa Press, USA

Distribution by the MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

Copyright 2022 Robert Hewison

The right of Robert Hewison to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 in the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means whatsoever without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and review and certain non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-913380-06-9 (hbk)

ISBN 978-1-913380-05-2 (ebk)

www.gold.ac.uk/goldsmiths-press

d_r0

Contents

I neither live nor work in Peckham, but I know people who do. Through them I have become fascinated by this ordinary and unusual part of London. I started to explore it in 2016, curious to know more about the artists who live there. It was a change from the books I usually write and, as I explain later in my introductory chapter, it turned into an experiment in a different way of doing cultural history. As I investigated, it became clear that a lot more people than artists live in Peckham, and that their lives have not been easy. Peckham began to reveal itself to me. Its history and the politics of its space became more and more interesting. But I allowed myself the freedom not to trace every possible connection, follow every lead, or tell every story that I heard. For practical reasons, most studies of this kind end up doing that, but I want to be honest.

The licence I gave myself turned out to be just as well because, as I was getting into my stride, the 2020 lockdowns came to hamper my research. Archives and libraries closed, and I could not meet as many people as I would have liked, for I strongly believe in meeting people face to face. Those that I have been able to see have been generous with their time and their comments, and I have shared as much as possible of the writing process with them. Interviewees specifically quoted in the text are thanked in the sources section that ends each chapter, but I would like to begin by thanking my former editor at Verso, Leo Hollis, for the very best critical advice. Tom Phillips got me started. Eileen Conn submitted to interrogation, and then closely read the final manuscript, picking up many mistakes. Benedict OLooney was generous with time and photographs; Jonathan Wilson welcomed me to Copeland Park and, in a sense, Hannah Barry gave me the idea in the first place. Russell Newell, who has contributed two fine photographs, became an important interpreter of community feelings that I would otherwise have found difficult to access.

Many people have helped in different ways, and I would like to thank: David Atua, Hakim Baghari, Humphrey Barclay, Gareth Bell-Jones, John Boughton, Dhanveer Singh Brar, Charmaine Brown, Clive Burton, Lewis Chaplin, Tim Crook, Anne and Trevor Dannatt, Bill Feaver, Martin Gayford, Camilla Goddard, Sophie Green, Margot Heller, Julian Henriques, Lucy Inglis, John D. Johnson, John Kieffer, John Kinrade, Noa Latham, John-Paul Latham, Harriet Latham, Gavin McKinnon-Little, John McTernan, Fred Manson, Lala Meredith-Vula, Siwan Moriarty, Jane Muir, Simon Mundy, Amanda Pryce, George Rowlett, Ben Sassoon, Richard Sennett, Raqib Shaw, Mickey Smith, Martin Stellman, the late Barbara Stevini, John-Paul Stonard, Liz Tang, David Thorp, Lily Tonge, Corinne Turner, Richard Wentworth, Natalie Wongs, Trix Worrell, Roger Young.

I would also like to thank especially Josephine Berry for spotting the opportunity, Susan Kelly of Goldsmiths Press for bringing it to fruition, and it goes without saying which is why I say it that EJB has been totally supportive throughout.

College House Cottage, 2021

I have chosen not to snag the reader with footnotes. Instead, they can find my key sources in the section at the end of each chapter. I hope that this feels more like a dialogue, but I acknowledge all the printed sources, as well as oral contributions. The photographic contributions are noted separately.

Quotations from Caleb Femis poems On Magic/Violence and On the Other Side of the Street, in Poor (Penguin Books, 2020) are by kind permission of Caleb Femi and Penguin Books.

Figure 1.1 Peckham 2022 (image credit: AZ Copyright (c) Collins Bartholomew Ltd 2021 (c) Crown Copyright and database rights 2021 Ordnance Survey 10018598).

The city is an oeuvre, closer to that of a work of art than to a simple material product.

Henri Lefebvre, The Specificity of Cities, in Writing on Cities, 1966

In 1948 Ealing Studios released its latest comedy, Passport to Pimlico. It is not about the whole of Pimlico, but takes us to a fictional Miramont Place: a village within a village, a small community undergoing the irksome deprivations and bureaucratic irritations of post-World War II austerity. In a situation that will become familiar here, the locals are battling with the borough council over proposals to redevelop an urban space. They want a lido; the council wants a factory. A chance discovery from Pimlicos past on the bombsite in question allows them to create a temporary utopia, released from regulation and rationing. But the free-for-all of crooks and dealers that follows an invasion by practitioners of what we now call the neoliberal economy divides the community until they reach an accommodation with the council, and, by extension, with authority. The planners and developers are frustrated; nonetheless, traditional hierarchical order is restored.

There is more than another pleasing alliteration in the title of this book, Passport to Peckham. Peckham is far larger than Miramont Place, and it has a considerably more varied population than the White, lower-middle class and working class in Ealing Studios comedy. But it is still a village not village in the sales-speak of developers and estate agents but a locally focused community, with all the tensions of village life, including struggles over living space and quarrels between allies. It began as a village, so small that it lacked a church. Its medieval street pattern created traffic problems that plague it still. It is also a village because it is informal, organic, without exact boundaries, and, more importantly, it is thought of as a place, rather than an administrative unit. Nobody planned Peckham.