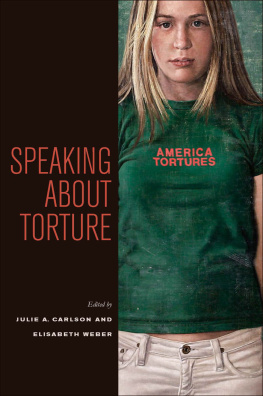

Speaking about Torture

Edited by

JULIE A. CARLSON AND ELISABETH WEBER

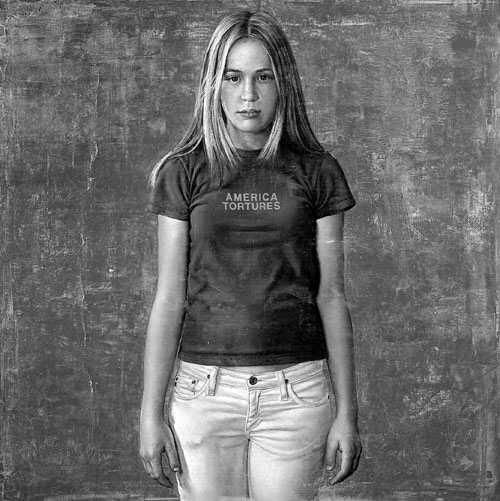

Frontispiece: John Nava, Signing Statement Law or An Alternate Set of Procedures, oil on canvas, 41 41 inches, from the series Neo-Icons, 2006. Courtesy of the artist and Sullivan GossAn American Gallery.

Copyright 2012 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Speaking about torture / edited by Julie A. Carlson and Elisabeth Weber. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

ISBN 978-0-8232-4224-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8232-4225-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Torture in literature. 2. Torture in mass media.

I. Carlson, Julie Ann, 1955 II. Weber, Elisabeth, 1959

PN56.T62S64 2012

809.93355dc23 2012002863

Printed in the United States of America

14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1

First edition

CONTENTS

JULIE A. CARLSON AND ELISABETH WEBER

LISA HAJJAR

ALFRED W. McCOY

REINHOLD GRLING

SUSAN DERWIN

ELISABETH WEBER

SINAN ANTOON

JOHN NAVA

ABIGAIL SOLOMON-GODEAU

STEPHEN F. EISENMAN

HAMID DABASHI

VIOLA SHAFIK

PETER SZENDY

CHRISTIAN GRNY

JULIE A. CARLSON

DARIECK SCOTT

COLIN DAYAN

RICHARD FALK

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the College of Letters and Sciences at UC Santa Barbara for selecting Torture and the Future for the Critical Issues in America lecture series in 2007, and especially David Marshall, the Dean of Humanities and Fine Arts, for his generous support of this project. We thank co-convener Lisa Hajjar for her initial vision and ongoing counsel, as well as committee members Roman Baratiak, Peter Bloom, Giles Gunn, and Nancy Kawalek. We thank our contributors for making the process of moving from live event to printed text an enlivening experience, and we thank Helen Tartar, the external reviewers, and the editorial staff at Fordham University Press for their endorsement of this volume and of the value of the humanities. We thank Charlotte Becker for her keen eye in helping us prepare the manuscript for publication.

The launching of any book evokes prospects whose structure of hope is embedded in the nature of writing. The prospect associated with ours is deeply imperiled. In that recognition, we mobilize our best things, including words, and dedicate this effort with love to David and Ruben Saatjian.

SPEAKING ABOUT TORTURE

For the Humanities

Julie A. Carlson and Elisabeth Weber

In his introduction to the collection Poems from Guantnamo: The Detainees Speak, published in 2007 by American and British lawyers who represent pro bono detainees of the camp, Marc Falkoff makes an observation, the implications of which underlie the impulse for this volume to speak about torture from the perspective of the humanities. Noting that the collection does not offer a complete portrait of the poetry composed at Guantnamo, largely because many of the detainees poems were destroyed or confiscated before they could be shared with the authors lawyers, Falkoff lists as a second inhibiting factor the Pentagons refusal to allow the publication of most of the existing detainees poems on the grounds that poetry presents a special risk to national security because of its content and formatthe ostensible fear being that detainees will try to smuggle coded messages out of the prison camp. In addition, he writes that most of the poems that have been cleared are in English translation only, because the Pentagon believes that their original Arabic or Pashto versions represent an enhanced security risk. As pertains to their translation, then, these poems are rendered in English by linguists whose special competency as translators of poetry resides in their secret-level security clearances, and

Leaving aside for the moment the question of how words do justice to the experiences about which these detainees speak, we wish to pause over the significance of these Poems from Guantnamo and the admission by Pentagon officials that they present a special risk to national security for the clarity with which they pose the question of the centrality of literature to the sustainability of human rights and their legislation, especially of those harder human rights such as the right not to be tortured. as well as claims to the originality, autonomy, and value of its speakers.

Yet these detainees speak, and in a mediumpoetrythat accommodates the limits that experiences of torture and trauma foreground. Through figuration, indirection, non-sense-making semiotic and affective processes, poetic discourse has long been said to grant space and even sanctuary to what precisely cannot be captured by logos. Assuming that media of transmission are not external to history and its representations, the American authorities, by disappearing the original languages of these poems and by classifying them as an enhanced security risk, attest to one of the structural conditions of witnessing: the fundamental possibility of untranslatability.

The remarkable admission, that the country that has at its disposal arguably the most technically advanced security apparatus sees itself threatened by the medium poem, especially the medium poem that is written in Arabic or Pashtoin other words, in languages whose potential of secret codes is deemed uncontrollablesignals some of what literature and humanistic endeavor bring to the project of legislating against torture: providing modes of witness that, through their powers of insinuation, may not be withstood. Of course, the admission is also remarkable because public discourse on torture as well as on the humanities generally proceeds from the opposite assumption: namely, that hermetic figurations of poetry and post-structural humanistic discourses distract and detract from consideration of urgent, real world policy issues such as torture, which is why such issues are best left in the hands of social scientists, political theorists, and military, legal, and government officials. We disagree. The essays in this volume explore how torture and humanist discourses each draw precise attention to the forms and histories of mastery, domination, and misrecognition lodged within concepts of truth. Consequently, we believe that efforts to address the long, though not continuous, history of justifying recourse to torture on the grounds of its capacity to uncover or extract truth from subjects deemed existentially untrustworthy require incorporating into policy discussions on torture the reconceptualizations of subjectivity, opposition, law, and representation that it has been the constant effort of humanist discourse, especially post-1945, to pursue.