The Food We Eat, the Stories We Tell

New Approaches to Appalachian Studies

Series editors: Elizabeth S. D. Engelhardt, Erica Abrams Locklear, and Barbara Ellen Smith

Gone Dollywood: Dolly Partons Mountain Dream, by Graham Hoppe

The Food We Eat, the Stories We Tell: Contemporary Appalachian Tables, edited by Elizabeth S. D. Engelhardt with Lora E. Smith

The Food We Eat, the Stories We Tell

Contemporary Appalachian Tables

Edited by Elizabeth S. D. Engelhardt with Lora E. Smith

With an Afterword by Ronni Lundy

OHIO UNIVERSITY PRESS ATHENS

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

ohioswallow.com

2019 by Ohio University Press

All rights reserved

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax).

Printed in the United States of America

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 195 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Engelhardt, Elizabeth S. D. (Elizabeth Sanders Delwiche), 1969-editor. | Smith, Lora E., 1979- editor.

Title: The food we eat, the stories we tell : contemporary Appalachian tables / Edited by Elizabeth S. D. Engelhardt with Lora E. Smith ; With an Afterword by Ronni Lundy.

Description: Athens : Ohio University Press, [2019] | Series: New approaches to Appalachian studies | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019028620 | ISBN 9780821423912 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780821423929 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9780821446874 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Food habits--Appalachian Region, Southern. | Cooking--Appalachian Region, Southern. | Appalachian Region, Southern--Social life and customs.

Classification: LCC GT2853.U5 F67 2019 | DDC 394.1/20975--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019028620

This book is dedicated to the next generation

of Appalachian foodways scholars, writers,

cooks, artisans, farmers, seedsavers, and

advocates

journey strong.

Contents

ELIZABETH S. D. ENGELHARDT |

LORA E. SMITH |

GEORGE ELLA LYON |

ERICA ABRAMS LOCKLEAR |

KARIDA L. BROWN |

DANIEL S. MARGOLIES |

JEFF MANN |

ABIGAIL HUGGINS |

ANNETTE SAUNOOKE CLAPSADDLE |

CRYSTAL WILKINSON |

COURTNEY BALESTIER |

MICHAEL CROLEY |

EMILY WALLACE |

ROBERT GIPE |

DANILLE ELISE CHRISTENSEN |

SURONDA GONZALEZ |

JESSIE BLACKBURN AND WILLIAM SCHUMANN |

EMILY HILLIARD |

REBECCA GAYLE HOWELL |

RONNI LUNDY |

Acknowledgments

This book would not be possible without the care and skillful attention of Gillian Berchowitz at Ohio University Press. Thank you for believing in our vision and shepherding this collection to print. Thank you to the authors included in this collection for sharing your intellect, research, wit, and stories. Our field is richer for your voices. A deep bow of gratitude to the foundational work to document and advance the study of Appalachian foodways by Ronni Lundy and Fred Sauceman. We stand on your shoulders and hope this collection invites more scholarship and inquiry into mountain foodways. And a special thank-you to the members of the Appalachian Food Summit for your ongoing work to create community and conversation through the stories of regional foodways.

Introduction

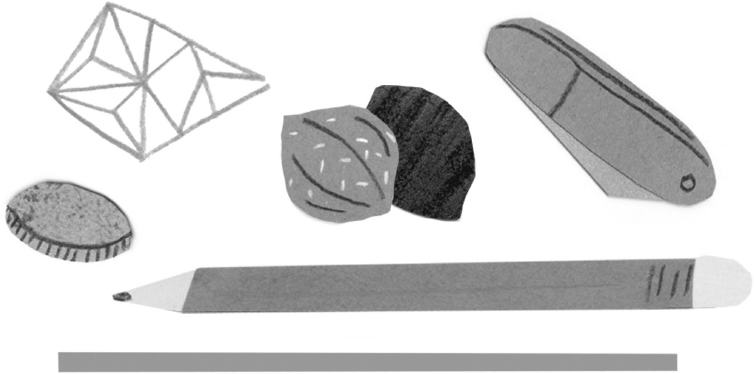

Two Walnuts, a Piece of Quartz, a Pencil, Dads Pocketknife, and a Quarter: Things I Carry

Elizabeth S. D. Engelhardt

THE WRITER Ursula K. Le Guin did not live in Appalachia. I dont know if she ever visited Mount Mitchell in North Carolina or Mount Le Conte in Tennessee. I dont know if she ever rested at the Peaks of Otter in Virginia or passed through the high country of West Virginia. I do know she lived in Portland, Oregon, within the large footprint of Mount Saint Helens, the volcano she called her neighbor in the Cascade mountain range of Washington. When Mount Saint Helens erupted in 1980, Le Guin was at the forefront of writers connecting ecology to literature to resilience and natures power in mountain communities. She passed away in January 2018, so we cannot ask her about the relation between eastern and western mountains and the cultures living with them. But we can say Le Guin defined herself with her mountains.

Le Guin also knew storytelling. In 1986, Le Guin wrote an essay entitled The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Ive been thinking about her piece during quiet moments this winter and spring. Its an essay meditating on the shapes of the stories we tell. She invites us to picture the arc of the flight of an arrow, with all its straightness, hardness, rise, fall, and penetration. That hunting arrow describes a dominant western popular culture definition of what a great story needs: vigorous action, a sharpened point, and the ability to wound, penetrate, or even kill. Its flightrising high into the air, climaxing, falling back to earthtraces classic advice for action, climax, denouement from countless writing manuals and high school English class textbooks.

Thats not the storytelling Le Guin finds compelling. She calls instead for stories that take the shape of the humble carrier bag. A bag is useful and practical; things in a bag brush up against each other and are always in relation to each other and to the container itself. Bags, with the things we carry in them, give us context and histories and possibility for futures. Novels, she argues, work best as containers. The novels she likes have beginnings without defined endings; the characters dont see everything clearly always; and they have space to avoid linear, progressive, Times-(killing)-arrow. They have people wandering around, bumping against each other, doing deeply human things in them. To Le Guin, this is the power of a novel and of storytelling; this is the version that can reveal us to ourselves.

Im not sure Ive ever seen Le Guin discussed in the circles of food studies to which I belong and with which the authors included in this volume are in conversation.

APPALACHIAN food and the people who grow, cook, preserve, sell, reject, transform, eat, and write about it exist in relation to mountains. Those mountains are physicalthey shape the ecologies of weather, water, soil, and life. Mountains are also cultural and metaphorical, constructed by social communities talking about them. What can be grown, what can be raised, what can be preserved and how, all is determined in some relation to mountains and hills. What tastes good, what is emblematic, what is avoided, and who gets a voice in deciding, all too develop with mountains in the discussion. Even in our stories of how people in Appalachia or connected to Appalachia try to avoid those mountainswhether by building transportation systems to ship foods from elsewhere, by reshaping the earth itself, by leaving or being pushed out, or by leveraging our identities in other racial, ethnic, or national cultures that bridge highlands and lowlandsthose people are doing so because of the stubbornly powerful presence of the mountains themselves.