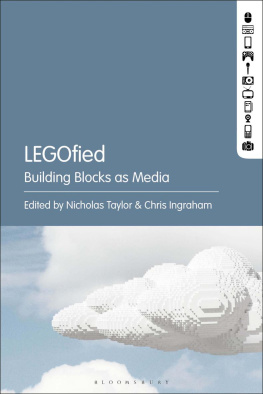

LEGOfied

LEGOfied

Building Blocks as Media

EDITED BY

NICHOLAS TAYLOR AND

CHRIS INGRAHAM

Contents

The cloud is a central motif in contemporary media studies. Both embraced and derided as a metaphor for a networked infrastructures invisible, off-site storage, clouds are meant to seem ephemeral and boundless but are, in practice, anything but. Clouds also figure powerfully in John Durham Peterss book about media, The Marvelous Clouds , but in this case referring literally to clouds floating in the sky. For Peters, media arent just technologies to transmit and circulate messages. The very elemental material of naturesea to sky, fire to cloudscan itself be understood as media. Media, Peters writes, are modes of being. And clouds in particular challenge the difference between media as vehicle and media as mode because their vapory being tests the outer limits of representation. This challenge is what LEGOfied is aboutas the marvelous clouds gracing its cover attests.

The cover image is a detail from an artwork called Hotel, by LEGO artist Nathan Sawaya and photographer Dean West, who combined their respective artistic media to offer an illusion in which the artificial and atomistic seems right at home, and almost indistinguishable, among the elemental and ephemeral. It is a testament to LEGO as a medium, and to Sawaya as an artist, that something so defined, so pixelated as LEGO can be used to communicate buoyancy and ephemerality. And yet, the playfulness of West and Sawayas art lies in trying to pick out the LEGO from the not-LEGO, to see if you can spot the subtle pixelation, the giveaway saturation, that reminds us that even the most lifelike LEGO sculpture is still LEGO. This is LEGOfication in its most rarefied and elemental form.

Nick

I would like to thank Danielle, first and foremost, for her love, patience and insight, and for allowing our house (not to mention endless conversations) to be steadily invaded by LEGO ever since I began this project in earnest; and Ben, my co-builder and inspiration, who represents so much of what is best about LEGO.

This work would simply not have been possible without the effort of the countless LEGO enthusiasts, artists, craftspeople, vendors, and more, whom we encountered at conventions and on social media. Their creativity and passion have served as both the impetus and the material for this book.

I would also like to thank Steve and Grant, for leaving their office doors ajar, and for their sage insights into how the pieces of this project might make this all fit together conceptually. Finally, I would like to acknowledge my incredible co-LEGOfiers: Sarah, Eddie, and Jess, for the research trip to San Diego; Kate, for providing the foundation; and Chris, for his limitless wisdom, enthusiasm, and warmth. Youve each helped transform what could have been a frustrating and alienating exercise into a source of continual insight and delight. Leg Godt!

Chris

Because this book would not exist without Nicks singular ability to take a personal interest and make it contagious by revealing its many fascinations and complexities, my heartiest thanks goes to Nick. If the highest purpose of art is to inspire, youre the consummate artistand a model friend and researcher alike.

Its also been an honor to work with such exceptional contributors. Eddie and Jess, Ive been learning from you since we were at NC State, where all this LEGOfying began. Kate and Sarah, Id always heard you were brilliant, but I didnt know you were this brilliant. Having Seth on board was the blessing and kindness that pulled it all together. Id also like to thank Scott Rettberg and Jill Walker Rettberg for hosting me at the University of Bergen as I worked on this project and traveled to Billund.

Most of all, though, my gratitude is due to Caroline, for indulging my newfound LEGO fandom (and the takeover of pieces across our home) that came with developing this book. What also came was lots of joyous hours playing and building LEGO and Duplo with my children, Mayer and Naomi. Det Bedste Er Ikke For Godt and you all are the best.

Seth Giddings

LEGO occupies a unique place within toy, play, and media culture. A hugely successful product line that is universally recognized, it has weathered, in over half a century, the turbulent seas of commercial childrens culturethe fads and crazes, the rise of competitors for attention, at first broadcast media, then the encroachment of digital culturefirst computer games, then networked social media. Along the way, the companys strategy picked up on the transmedial trajectory and occupied it emphatically. The characteristic studs, patented in the 1950s, are instantly recognizable, as much a sign or logo as they are a technical feature of the construction toy. Since the 1970s, LEGO minifigures have risen to prominence in a cluttered cultural economy of attention, intellectual property as familiar as the Disney Princesses or the Super Mario pantheon. Studs and minifigures are found now in films, TV animation, videogames, their chunky modularity endlessly flexible across franchises and storyworlds as well as across bedroom and living room floors.

The LEGO Groups own self-presentation and publicity, its longevity, and of course the toys distinct design and material characteristics have fed into a persistent sense of the toy as more than just another plastic product. Though appeals to and critiques of LEGO (and its changes over recent decades) are varied and often contradictory, they are near-universally underpinned by assumptions that LEGO is (or was) a unique toy or system, distinct in its flexibility and open-endedness in play. LEGO is scaffolded by a popular imaginary, of an educational or imaginative toy that promotes creativity in ways closed off in other toys. It haslike Disney, that other persistent staple of commodified childrens culture in the late twentieth centurya set of moral expectations. Both have been entrusted with the imaginations of generations of children, wholesome fantasy from Disney, educative fun from LEGO, each exploiting the assumption of an extra-commercial responsibility for childrens development. Like Disney, LEGO has had to carefully negotiate these expectations of their contribution to an idealized childrens culture with hard-nosed industrial strategies of licensing, transmedial franchises, and extensive merchandising in a rapidly changing technocultural economy. From the late twentieth century, both media empires have embraced and hypercharged transmedial tactics, breaking down the walls of their ethico-symbolic storyworlds, abandoning corporate-cosmological purism for the cross-pollination of proprietorial supersystems.

Though changes to the packaging and media positioning of the toy, and its spreading out into other media and digital forms, have generated popular hostility and journalistic claims of betrayal, LEGO (or rather the LEGO System) has over the decades gathered about itself an imaginary: a set of implicit and explicit concepts of its transcendence over other ordinary toys and childrens media. It is an imaginary that privileges an idealized imagination: the design and dissemination of LEGO, its proponents assert, engenders creative, open-ended play; its flexibility drives productive engagement in the moment of play, and the development of cognitive skills and creative aptitudes over time. Its near-mythic status as an ur-toy has been consistently invoked as an ideal from which every incremental change in design and marketing since the 1950s has been perceived as a fall from grace. The remarkable and promiscuous franchising of recent years, culminating in LEGO Dimensions games mixing up characters from Lord of the Rings , Batman , and the like, back to the introduction of LEGO Friends targeted at girls, to themed sets with specialized bricks, the inclusion of instructions, back even to the illustration of possible constructions on the lid of early boxes in the 1960s, and so on. Generations of LEGO critics have and continue to hark back to a prelapsarian idyll (usually of their own childhood) when the toy was more creative.