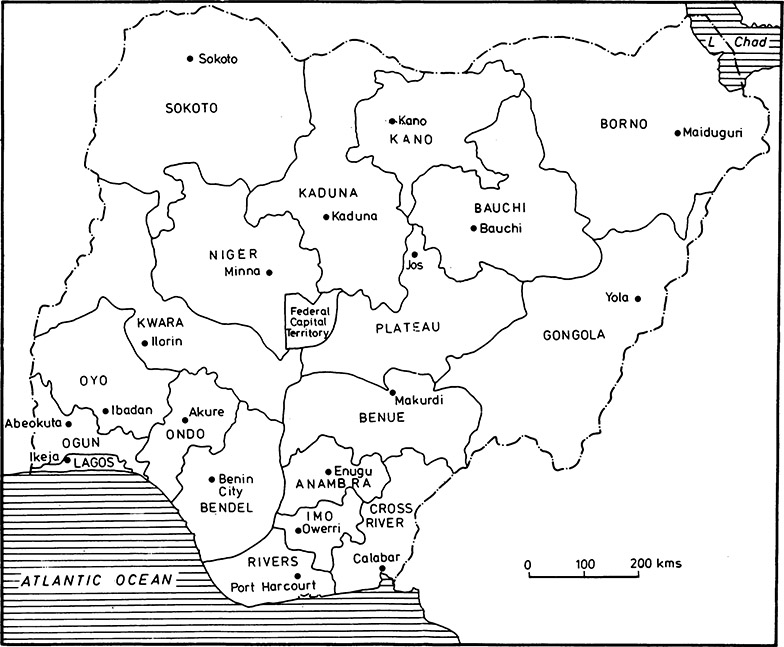

Nigeria came under military rule on 15 January, 1966, went through a gruesome civil war in 196770, and returned to civilian rule on 1 October, 1979, after a planned process of authority transfer which began in earnest four years before on 29 July, 1975.

This book is a critical study of the evolution and conduct of military government as well as civil-military relations in Nigeria since 1970. critically examines the essentially military clauses of both the draft and final Constitution drawn up for post-1979 Nigeria, against the background of contending concepts of civil-military relations.

The most statistical and quantitative of them all, extraction from society over the period. The chapter specifies what is meant by the term military extraction. The assumption here is that if modernisation under military aegis exceeded the ratio of military extraction, then the impact of the military could hypothetically be considered positive; but definitely negative, if the contrary was demonstrated to have been the case.

finished, demobilisation. It accepts the premise that the 250,000 member army, with which Nigeria was saddled at the end of the civil war in 1970, was too large for the countrys subsequent needs. But can there actually be anything like an optimum military size? This part of the book argues, against popular view to the contrary, that such ideals do not lend themselves to precise mathematical calculations. It is conceded nonetheless that certain factors determine both the upper and lower limits of any national military size. The seven advanced factors are: a countrys geographical extent, size of population, level of technical resources, available national wealth, nature of strategic thinking and whether offence or defence oriented, extent of foreign commitments, and incidence or likelihood of war involvement. The ideal is critically evaluated as applied to the contemporary Nigerian situation.

The final chapter reverts to some of the arguments put forward in of the study, especially the point that civilian control cannot be achieved by mere constitutional engineering. It was naive on the part of the Constituent Assembly members, who subsequently considered the draft Constitution for ratification, to think that military return to power through future coups could be prevented, by a formally entrenched constitutional provision. The study ends by suggesting factors of a general and specific nature likely to affect the stability, or instability, of the Nigerian civil-military system after 1979.

Earlier drafts of the first three chapters of this book were presented at various conferences held between 1977 and 1979 at home or abroad. The first was at the Eighth General Conference of the International Peace Research Association (IPRA) which took place at Knigstein, Federal Republic of Germany, 1823 August, 1979. Part of the second chapter was read at the National Conference on Issues in the Draft Constitution, Institute of Administration, Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria, 2124 March 1977; while the third was delivered at the Fifth Annual Conference of the Nigerian Political Science Association (NPSA), University of Ife, Ile-Ife, 36 April, 1978.

Many colleagues participating in these conferences provided comments and criticisms found useful in re-working the chapters concerned, and for these the author is grateful. I would also like to thank Eyitomilayo, who proved more than a better half in her unstinted moral and academic support. In the profound sense, this book is our joint work. And yet, ultimately, I alone bear full responsibility for all its deficiencies and errors.

J. Bayo Adekson,

Ibadan,

September, 1980.