T HE W ALL

THE CHEERFUL PAINTINGS OF FLOWERS on the tall metal posts on the Tijuana side of the border fence between the U.S. and Mexico belie the sadness of the Mexican families who have gathered there to exchange whispers, tears, and jokes with relatives on the San Diego side. Many have been separated from their family members for years. Some were deported to Mexico after having lived in the United States for decades without authorization, leaving behind children, spouses, siblings, and parents. Others never left Mexico, but have made their way to the fence to see relatives in the United States. With its prison-like ambience and Orwellian nameFriendship Parkthis site is one of the very few places where families separated by immigration rules can have even fleeting contact with their loved ones, from a.m. to p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays. Elsewhere, the tall metal barrier is heavily patrolled.

So is to be the wall that President Donald Trump promises to build along the border. But no matter how tall and thick a wall will be, illicit flows will cross.

Undocumented workers and drugs will still find their way across any barrier the administration ends up building. And such a wall will be irrelevant to those people who become undocumented immigrants by overstaying their visaswho for many years have outnumbered those who become undocumented immigrants by crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.

Nor will the physical wall enhance U.S. security.

The border, and more broadly how the United States defines its relations with Mexico, directly affects the million people who live within miles of the border. In multiple and very significant ways that have not been acknowledged or understood it will also affect communities all across the United States as well as Mexico.

What the Walls Price Tag Would Be

The wall comes with many costs, some obvious though hard to estimate, some unforeseen. The most obvious is the large financial outlay required to build it, in whatever form it eventually takes. Although during the election campaign candidate Trump claimed that the wall would cost only $ billion, a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) internal report in February put the cost at $. billion, but that may be a major underestimate.

The estimates vary so widely because of the lack of clarity about what the wall will actually consist of beyond the first meager Homeland Security specifications that it be either a solid concrete wall or a see-through structure, physically imposing in height, ideally feet high but no less than feet, sunk at least six feet into the ground to prevent tunneling under it; that it should not be scalable with even sophisticated climbing aids; and that it should withstand prolonged attacks with impact tools, cutting tools, and torches. But that description doesnt begin to cover questions about the details of its physical structure. Then there are the legal fees required to seize land on which to build the wall. The Trump administration can use eminent domain to acquire the land but will still have to negotiate compensation and often face lawsuits. More than such lawsuits in southern Texas alone are still open from the 2008 effort to build a fence there.

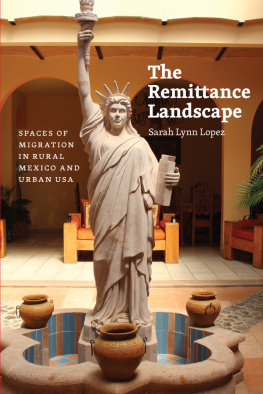

The Trump administration cannot simply seize remittances to Mexico to pay for the wall; doing so may increase flows of undocumented workers to the United States. Remittances provide many Mexicans with amenities they could never afford otherwise. But for Mexicans living in povertysome . percent in 2015 according to the Mexican social research agency CONEVALthe remittances are a veritable lifeline which can represent as much as percent of their income. These families count on that money for the basics of lifefood, clothing, health care, and education for their children.

I met the matron of one of those families in a lush but desperately poor mountain village in Guerrero. Rosa, a forceful woman who was initially suspicious, decided to confide in me. Her son had crossed into the United States eight years ago, she said. The remittances he sent allowed Rosas grandchildren to get medical treatment at the nearest clinic, some thirty miles away. Like Rosa, many people in the village had male relatives working illegally in the United States in order to help their families make ends meet. Sierra de Atoyac may be paradise for a birdwatcher (which I am), but Guerrero is one of Mexicos poorest, most neglected, and crime and violence-ridden states. Here you have few chances, Rosa explained to me. If youre smart, like my son, you make it across the border to the U.S. If youre not so smart, you join the narcos . If youre stupid, but lucky, you join the [municipal] police. Otherwise, youre stuck here farming or logging and starving.

Any attempt to seize the remittances from such families would be devastating. Fluctuating between $ billion and $ billion annually during the past decade, remittances from the United States have amounted to about percent of Mexicos GDP, representing the third-largest source of foreign revenue after oil and tourism. The remittances enable human and economic development throughout the country, and this in turn reduces the incentives for further migration to the United Statesprecisely what Trump is aiming to do.

Why the Wall Wouldnt Stop Smuggling

Why the DHS believes that a -foot tall wall cannot be scaled and a tunnel cannot be built deeper than six feet below ground is not clear. Drug smugglers have been using tunnels to get drugs into the United States ever since Mexicos most famous drug trafficker, Joaqun El Chapo Guzmn of the Sinaloa Cartel, pioneered the method in 1989 . And the sophistication of these tunnels has only grown over time. In April 2016 , U.S. law enforcement officials discovered a drug tunnel that ran more than half a mile from Tijuana to San Diego and was equipped with ventilation vents, rails, and electricity. It is the longest such tunnel to be found so far, but one of of great length and technological expertise discovered since 2006 . Altogether, between 1990 and , tunnels have been unearthed at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Other smuggling methods increasingly include the use of drones and catapults as well as joint drainage systems between border towns that have wide tunnels or tubes through which people can crawl and drugs can be pulled. But even if the land border were to become much more secure, that would only intensify the trend toward smuggling goods as well as people via boats that sail far to the north, where they land on the California coast.

Another thing to consider is that a barrier in the form of a wall is increasingly irrelevant to the drug trade as it is now practiced because most of the drugs smuggled into the U.S. from Mexico no longer arrive on the backs of those who cross illegally. Instead, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, most of the smuggled marijuana as well as cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamines comes through the legal ports of entry on the border. These ports have to process literally millions of people, cars, trucks, and trains every week. Traffickers hide their illicit cargo in secret, state-of-the art compartments designed for cars, or under legal goods in trailer trucks. And they have learned many techniques for fooling the border patrol. Mike, a grizzled U.S. border official whom I interviewed in El Paso in 2013 , shrugged: The narcos sometimes tip us off, letting us find a car full of drugs while they send six other cars elsewhere. Such write-offs are part of their business expense. Other times the tipoffs are false. We search cars and cars, snarl up the traffic for hours on, and find nothing.