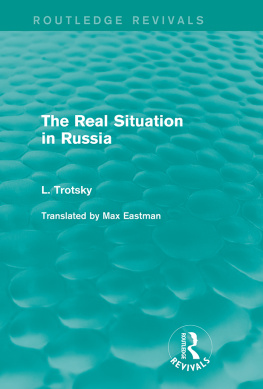

Routledge Revivals

Towards Socialism or Capitalism?

First Published in 1926, Towards Socialism or Capitalism? considers the socialist economy of Soviet Russia, isolated in a capitalist world after Lenins death, faced acute dangers. Trotsky and the Left Opposition alone fought the Stalinist degeneration of the state and party apparatus which threatened to open the door to capitalist restoration. The three articles in this book, written between 1925 and 1932, discuss the fundamental problems of the Soviet economy from the New Economic Policy to forced collectivization. Published here in one volume, they are indispensable steps in the development of Trotskys analysis of the Soviet Union, laid down in 1936 in The Revolution Betrayed.

First published in 1926

by Methuen & Co. LTD

This edition first published in 2012 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1926 Methuen & Co. LTD.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under ISBN: 27022460

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-62338-4 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-203-10292-3 (ebk)

TO THE ENGLISH READER

T HIS book is an attempt to estimate the true value of the foundations of our economic development. The difficulty of an evaluation of this kind lies in the sharp break made by our development. When a movement proceeds along a straight line, two points are sufficient to determine its course. On the contrary, should development describe a complex curve the estimation of each separate section becomes a difficult matter. And the eight years of the new regime are merely a small section.

Our opponents, however, and our enemies have repeatedly passed severe judgment on our economic developmentand that long before the eighth anniversary of the October Revolution. Their judgments follow two lines : In the first place they tell us that in building up socialist economics we are ruining the country, in the second they say that in developing our productive forces, we are practically marching towards capitalism. The first method of judgment is characteristic of pure bourgeois thought ; the second is as typical of social democratic, i.e. disguised bourgeois ideology. There is no sharp line of demarcation between the two types of criticism and the two often exchange weapons in a neighbourly waywithout noticing it themselvesin the intoxication of their battle against communist barbarity.

The present work will show, I hope, to the unbiassed reader that the outspoken big bourgeois and the petty bourgeois masquerading as socialist deliberately pervert the truth. They do so when they say that the Bolsheviks have ruined Russia. The most incontestable evidence bears out the fact that in Russia, ruined first by the Imperialist war and then by the civil war, the productive forces of trade and agriculture are reaching the pre-war level which will be attained in the course of the current year. They are also wrong when they say that the development of our productive forces proceeds on capitalist lines. In all branches of the economic lifein industry, transport, trade, the credit systemthe predominance of State management far from diminishing with the growth of the productive forces, is steadily increasing. This is fully borne out by figures and facts.

The problem of agriculture is a much more complicated one, and there is nothing surprising in this to the Marxian mind. The change from the system of small individual peasant holdings to socialist methods of land cultivation is only conceivable after a number of consecutive stages of progress in technical science in economics and culture. The all important condition of the change is that power should remain in the hands of the class whose object is to lead the community towards socialism and which gains more and more ability to influence the peasantry by means of State industry, improved scientific agriculture, creating thereby premises for a transition to collective methods of cultivation.

We have obviously not yet solved this problem. We are only creating the premises for a consecutive and gradual solution of it. These very premises, however, develop new disparities and pitfalls. What are they ?

At present the State places on the market fourfifths of the industrial produce, while about onefifth falls to the share of private enterprise, provided practically by the petty home industries. Railway and water transport is entirely in the hands of the State. State and co-operative trade now covers nearly three-quarters of the trade turnover. Ninety-five per cent. of the foreign trade is in the hands of the State. Credit institutions form a centralised State monopoly. This mighty State combine, however, is confronted by no less than 22,000,000 of peasant holdings. A combination of State economics and peasant economics subject to the general growth of the productive forces at present constitutes the fundamental social problem of socialist progress in our country.

The growth of the productive forces is an indispensable condition to the achievements of socialism. At the present level of economic development and culture, the growth of the productive forces is made possible only by the inclusion of the individual interest of the producers into the scheme of communal economics. In regard to industrial workers, this is secured by making the wages dependent on output. Much success has already been achieved in this direction. In regard to the peasants, personal interest is secured by the very existence of individual holdings and their participation in the market. But there are also difficulties arising from the same fact. Differences in the scale of wages, however considerable they may be, do not lead to a stratification of the proletariat ; the workers, no matter what their wages are, remain workers employed in State factories and works. The case is different in regard to the peasants. With 22 millions of peasant holdings working for the market, the State farms, collective peasant farms and agricultural communes forming but an insignificant minority among them, we are inevitably led to the position where on the one end of the peasant masses we have not only prosperous but exploiting farms, and on the other, a part of the less prosperous falling into pauperism, and paupers becoming hired labourers. When the Soviet Government, on the advice of our Party, introduced the New Economic Policy and widened its scope in regard to the land, it was quite aware of the inevitable social results on the economic system, as well as of the political dangers it involved. However, we regard these dangers not as fatal consequences to be accepted, but as problems which have to be carefully analysed and solved at each successive stage of our development.