Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art courtesy of Shutterstock

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-17455-6

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Baskerville 120 Pro and

Berthold Akzidenz Grotesk

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

PREFACE

The Tax Revolt Was a Long Time Ago

When I tell people I study Americans opinions about taxation, their reactions are predictable. First, a pained look usually passes across the face of my interlocutor, as he or she regrets asking me about my presumably dreary work. Second, he or she informs me that Americans hate taxes. Americans are angry, Im told, or selfish, or shortsighted, or prefer to be self-sufficient and are therefore intrinsically anti-government. For one reason or another, Americans just do not want to pay the governments bills.

This popular vision of Americans as anti-tax ideologues surely draws some of its power from the media. On Fox News, conservative pollster Frank Luntz told Bill OReilly that taxes are an emotional issue for the voters because nobody wants their taxes to go up. Journalist Maria Bartiromo, hosting a 2015 Republican presidential primary debate, insisted there isnt anyone in this audience or watching at home tonight who would not like to pay less in taxes. Perhaps surprisingly, this vision of the American public is common on the political left as well. On CNNs

As in the popular press, public opinion polls commonly assume that the only attitude Americans hold about taxes is one of enraged opposition. For instance, Gallup regularly asks, Which of the following bothers you most about taxes? and Which do you think is the worst taxthat is, the least fair? For good reason, most survey questions are not asked this way; negative questions carry a value judgment and predispose certain answers. And these questions collect only half the range of possible views. Asking people what is most bothersome about taxes ignores the possibility that they are not bothered. That the income tax is often chosen as the worst tax has very different implications when one learns, as I did in the course of my research, that it is equally commonly picked as the best tax. And yet tax questions are persistently asked in the negative.

The idea that Americans hate taxes has become a truism without the benefit of being true. Instead, Americans see paying taxes as a civic obligation and a political act. To be a taxpayer, Americans believe, is something to be proud of. It is evidence that one is a responsible, contributing, and upstanding member of society, a person worthy of respect in the community and representation in the government.

My work on taxes builds on a substantial body of scholar-ship that has looked at attitudes about public spending, and gives lie to the notion that Americans are knee-jerk opponents of government. Dating back at least to the work of the path-breaking social scientists Lloyd Free and Hadley Cantril in the late 1960s, scholars of public opinion have recognized that, though Americans tend to agree in principle with small government, they simultaneously approve of major public investments in economic opportunity.

In the face of so much contradictory evidence, how can we explain the longevity of the popular conviction that Americans hate taxes? It is hard to say with certainty, but one event within living memory seems to have played an outsized role in the consciousness of politicians, journalists, scholars, and perhaps the public as wellthe tax revolt.

Similar measures were soon on the agenda in states across the country, in what came to be known as the tax revolt. The tax revolt shocked elites at the time and, only a few years later, was seen as the harbinger of the end of the New Deal consensus and the dawn of Reagan-era welfare state retrenchment. For scholars, too, the tax revolt became a touchstone. Much of the best research on tax attitudes dates to that era, as scholars attempted to understand what appeared to be a fundamental reorientation of American politics.

The origins of the tax revolt in California were not a popular clamoring for the Reagan Revolution, but instead a demand for government protection against housing market vagarieswhat amounts to a social program delivered via the tax code.

The prominence of the tax revolt and the persistence of tax opposition as a rallying principle of the Republican Party disguise fundamental changes in American tax politics.

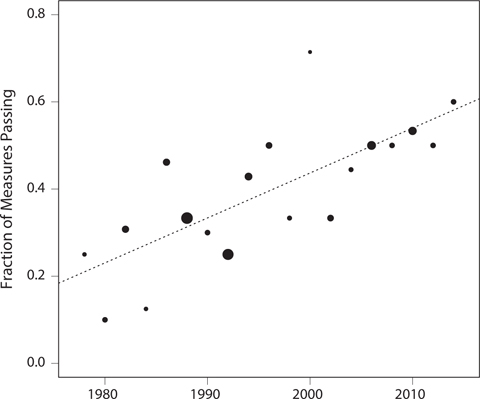

That times have changed is evident on the home field of the tax revolt, the state ballot measure. Over the past three and a half decades, state ballot measures intended to raise taxes have steadily had more success (

Moreover, many different kinds of taxes have been successfully increased by popular vote. The list of successful tax increases includes both measures targeted at the wealthy and broad-based taxes affecting nearly all state residents. And these measures are not just raising small change, either. In 2010 voters in Oregon raised their top income tax rates and their corporate minimum tax, while voters in Arizona raised the sales tax. Each bill was worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

Meanwhile, measures to cut taxes have dwindled in their significance. In stark contrast to sweeping measures like Proposition 13, tax cut ballot measures are now often what you might call Grandma and Apple Pie measures: legislation that offers a small additional property tax credit to seniors, military veterans, the disabled, and their surviving spouses. In Colorado in 2006 a measure appeared on the ballot to reduce the property taxes paid by veterans rated as 100% disabled due to their military service. The state estimated the measure would affect a little over two thousand people, and would save each veteran perhaps as much as $500. The voters were very willing to be generous to such worthy beneficiaries; nearly four in five Colorado voters voted in favor of the 2006 measure, a tiny cost to the state that might slightly ease the finances of a few of the states wounded warriors.

F IGURE 0.1. The Success of Tax-Increasing State Ballot Measures, 19772014

Note: Dot size is relative to the number of measures in a two-year period. Dotted line is a simple line of best fit. (OLS, or ordinary least squares, is a mathematical calculation that fits a line through a scatter of data to highlight the overall pattern. One way to visualize this process would be to draw a vertical line from each dot to the line, and imagine how tilting the line would change those distances. Technically speaking, OLS finds the line that minimizes the sum of the squares of those vertical distances.)