Energy Politics in Colombia

Energy Politics in Colombia

Ren De La Pedraja

First published 1989 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1989 by Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

De La Pedraja Tomn, Ren.

Energy politics in Colombia / by Ren De La Pedraja.

p. cm.(Westview special studies on Latin America and the

Caribbean)

Includes index.

ISBN 0-8133-7655-6

1. Energy policyColombia. 2. Natural resourcesGovernment

policyColombia. I. Title. II. Series.

HD9502.C72D4 1989

333.79'09861dc19 88-11098

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-01270-0 (hbk)

To Beatriz

Only a collective thank-you can go to those institutions and many individuals who at considerable risk have provided much of the information on which this book is based. Anonymity may not be enough protection for them; I still hope for a day in Colombia when they may be mentioned without fear of reprisal and without accelerating the destruction of compromising evidence. I have done everything possible to verify and compare this information with that available in U.S. and British archives as well as in the public recordall sources that contribute valuable dimensions of their own. The referees' comments have contributed to the final shape of this book.

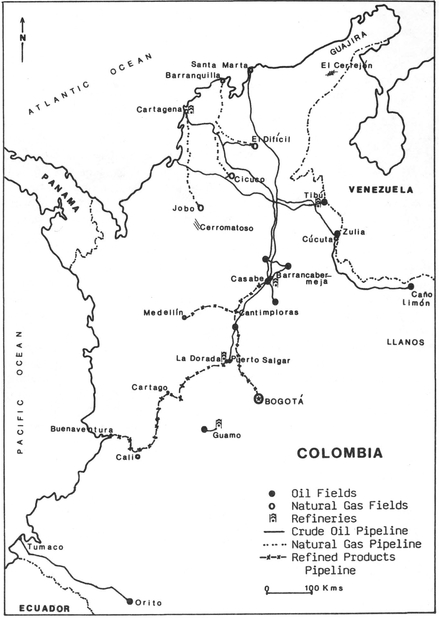

The staffs at the various archives and libraries I consulted were unfailingly helpful. Support from Kansas State University for the final research is greatly appreciated. Nedra Sylvis typed the manuscript with her usual precision. Special thanks go to Helen Toman, as well as to Elvira and Terry Buttler. My son, Jaroslav, helped classify the seemingly endless piles of documents and clippings, while my wife, Beatriz, once again patiently read and improved upon the text, a gigantic effort in itself, and also drew the maps. More important, she provided intelligent support for home and family life during a particularly trying time in our careers, until at last this book could fend for itself.

Ren De La Pedraja

Why has Latin America remained an economically underdeveloped and generally poor area in spite of the abundance of natural resources of the most varied kinds? The example of Colombia, the third most populated country in Latin America, clearly shows that the failure to replace human and animal power with ever-increasing amounts of mechanically derived forms of energy has been one of the causes of poverty among Latin Americans; it has also helped create fertile ground for recurrent political strife.

My previous book, Historia de la energa en Colombia, 1537-1930, revealed how the country lagged from the very start in meeting the energy needs of its economy, but one question remained unanswered: Why did Colombia fail to properly utilize its vast reserves of coal, hydroelectricity, and petroleum, not to mention its other mineral resources? This book, covering the period since 1920, attempts to provide an answer to this question by examining Colombia's policies concerning a broad range of representative energy development projects.

The Industrial Revolution in Europe had at its very center the application of iron and coal to produce steam power, yet Colombia during the nineteenth century largely failed to incorporate these new advances, as witnessed by the limited spread of steam navigation in the inland rivers and railroads; no more successful was the use of steam to power the incipient shops and the handful of factories. It was only in 1890, when Europe and the United States were already in the middle of the Second Industrial Revolution, that Colombia began to install small generating plants; by 1910 all the major cities enjoyed regular electricity service, although in limited amounts. Small as it was, this stimulus provided by the gradual spread of electricity was at the very core of the onset of industrialization from 1890.

By 1930, even before the Great Depression struck, this first stage of both industrialization and electrification had run into deep trouble. As the private Colombian utilities increased their capacity to transform a backwards and agrarian country, they faced a rising tide of obstacles. Contemporaries agreed that both the utilities and the factories were starved for capital, disregarding, however, signs that other problems also caused the first stage of industrialization, which had never been very hectic, to peter out by 1930.

Where could additional capital be found? The government and private sectors were both financially strained. By the late 1920s the only remaining source of capital ready at hand was to be found in Colombia's large petroleum fields, whose black liquid flowed on the surface, making unnecessary any prospecting or exploratory drilling. Oil revenues would thus finance a vast expansion of hydroelectricity, as well as of industry, However, since government concessions had already granted the two known main oil fields to US. companies, a decisive struggle ensued. This is where the first chapter of this book begins.

PART ONE

Petroleum and Natural Gas

The First Nationalistic Campaign

Exxon had adroitly maneuvered during the 1910s to acquire the Barrancabermeja field, and Gulf Oil Co, (owned by Andrew Mellon) did the same to acquire the Barco Concession near Ccuta ( A faction within the Colombian elite felt that this situation was unacceptable, and during the presidency of Miguel Abada Mndez (1926-1930), Minister of Development Jos Antonio Montalvo led the dissatisfied elements in a campaign to reverse Colombia's petroleum policy and rescue the Barco Concession.

The presidency of Abada Mndez witnessed the gradual shift of power from the ruling Conservative Party, dominant in Colombia since the end of the nineteenth century, to the revitalized opposition Liberal Party. Conservative leaders were not unaware of their crumbling position, and to gain a new lease on life, the faction around Montalvo decided to start a nationalistic campaign over petroleum. Their two related goals were to regain popularity, and hence votes, and to increase the revenue received from the Barrancabermeja oil field. The government needed the

How could the rate be revised in the face of this contract?

Exxon had imposed on Colombia the standard practice shared by other oil companies of never giving up even the smallest acquired privilege, so that when Montalvo sounded out Exxon about increasing the crude royalty rate from 10 to 15 percent, he received an indignant rejection. This refusal forced the Minister of Development to study events in Mexico more closely, and he soon learned that U.S. oil companies became more conciliatory when the state played them off against rival British companies. After preliminary soundings, Montalvo discovered that the English company most interested in Colombia was British Petroleum, which controlled the rich oilfields in Iran but wished to diversify. British Petroleum had the added advantage of partial ownership by His Majesty's Government, thus assuring strong diplomatic support from London to counter the pressures from the State Department. A minor irritant was Colombian law, which, in order to prevent another Panama, forbade granting oil concessions to companies having foreign states as major stockholders.