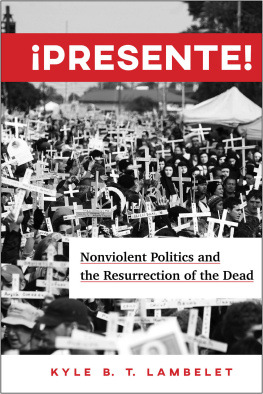

PRESENTE!

PRESENTE!

Nonviolent Politics and

the Resurrection of the Dead

KYLE B. T. LAMBELET

2019 Georgetown University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for third-party websites or their content. URL links were active at time of publication.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lambelet, Kyle Brent Thompson, author.

Title: Presente!: Nonviolent Politics and the Resurrection of the Dead / Kyle B.T. Lambelet.

Description: Washington, DC : Georgetown University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019005026 (print) | LCCN 2019022054 (ebook) | ISBN 9781626167278 (ebook) | ISBN 9781626167254 (hardcover : qalk. paper) |

ISBN 9781626167261 (pbk. : qalk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Nonviolence--Religious aspectsChristianity. | Political theology. | PeaceReligious aspects. | U.S. Army School of the Americas.

Classification: LCC BT736.6 (ebook) | LCC BT736.6 .L35 2019 (print) | DDC 241/.697dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019005026

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

20 199 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 First printing

Printed in the United States of America.

Cover design by Martha Madrid.

Cover photograph by Linda Panetta | Optical Realities Photography | www.OpticalRealities.org

This book is dedicated to all those whose persistent,

resurrected presence disturbs and inspires the work

against the violence of empire and for peace

with justice, especially Mike, Eli, and Jerry. Presente!

As Jon Sobrino wrote, May their peace give us hope,

and may their memory never let us rest in peace.

For if the dead are not raised, then Christ has not been raised. If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have died in Christ have perished. If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied.

1 Corinthians 15:1619, NRSV

I have often been threatened with death. I must tell you, as a Christian, I do not believe in death without resurrection. If I am killed, I shall arise in the Salvadoran people.

scar Romero in an interview with Jos Caldern Salazar two weeks before his assassination

The security of the resurrection does not take away the desire to struggle but strengthens it. As a follower of Jesus, one tries to do this out of hope.

Ignacio Ellacura,

The Christian Challenge of Liberation Theology

We have seen that the infamous SOA is not just a building; it is not just a policy. The School is a mindset with roots as old as the colonization of the Americas. It is the belief that land, resources and human rights are commodities that can be bought, stolen and destroyed. In that mindset there are no ancestors, no memory, and no imagination. Inside that set of beliefs Celina, Elba and the six Jesuits were dangerous enough to assassinate but not human enough to have a right to live.

Liz Deligio, SOA Watch activist

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I first attended the annual vigil of the School of the Americas Watch in 2005. I had graduated earlier the same year with an undergraduate degree in theology and had set about looking for concrete embodiments of the radical ideas I had encountered in the classroom. This search brought me to a Catholic Worker community in Atlanta, and with these workers I traveled to Columbus, Georgia, where the annual event was held. For most of my companions, this was a site of annual pilgrimage. For me it was a first. What I experienced on that chilly November morning at the gates of Fort Benning impacted me profoundly.

At the time the United States was fighting two warsone in Afghanistan and another in Iraqand in the year prior the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal had come to light. The consensus among those of us who traveled to Fort Benning was that the torture of detainees was not an aberration, the work of some bad apples. Rather, seemingly indiscriminate torture for counterinsurgency purposes came straight from the playbook of the training manuals that instructors used in the US Armys School of the Americas (SOA) until the mid-1990s. The torture and assassinations that had plagued Latin America through the second half of the twentieth century were spreading to Iraq and beyond.

Arriving at the gates of Fort Benning early that Sunday morning, the scene was electric. Though I had participated in massive anti-war protests in Los Angeles during the buildup to the US invasion of Iraq, this felt different. Tens of thousands of people from across the country and the globe gathered in this relatively remote location. There were women religious, Food Not Bombs anarchists, Jesuit high school students, southern civil rights activists, Central American sanctuary recipients, Veterans for Peace, and many, many others. What brought this wildly plural group together was the presente! litany, an hours-long protest liturgy in which the names of those who had been tortured and killed by the graduates of the SOA/Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC) were sung and claimed responsively as presente, present. Though the congregated mass was remarkably diverse, the people figured out a way to coordinate their bodily movements together in affirming the presence of the dead.

My first exposure to SOA Watch activism was overwhelming. Afterward, my fellow Catholic Workers and I made our way to a Chinese buffet in Columbus, and we reflected on what we had just experienced. Looking around at my companions, many of whom were wearing shirts that boldly proclaimed NO WAR! I suggested that the protest was a way of saying no and saying yes: we said no to war, to torture, and to empire while also saying yes to solidarity, to nonviolence, and to a communion that transcends death.

I lacked at the time the conceptual vocabulary or the analytical tools to probe my experience, but I left my first SOA Watch vigil with a constellation of questions: What political work does this theologically and viscerally powerful action do? How does it perform that work within a context of such religious, ideological, and identity-based diversity? What is the relationship between this action, the civil disobedience committed annually at the gates, and the ongoing work of lobbying for legal reform? What role does the images and stories of the martyrs play in shaping movement participation? And, most of all, what does it mean for us to claim the presence of these dead in this place?

This book, completed nearly a decade and a half after my first trip to the gates of Fort Benning, responds to these questions.

After returning to the SOA Watchs annual mobilization several times as a participant and then several more times as a researcher (participant-observer), after dozens of official and unofficial interviews with SOA Watch activists and organizers, after participating in an SOA Watch delegation to the US-Mexico border, and after combing through personal archives of several SOA Watch prisoners of conscience, I have a better sense of the impact of the claim of presente not only on my own life but also on the lives of the transnational grassroots network of SOA Watch activists. The messianic claim that the dead are presente shapes a distinctive, transnational, and nonviolent politics.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.