Contents

Guide

Page List

THE NEW MONUMENTS

AND THE END OF MAN

_____________________________________

THE NEW MONUMENTS

AND THE END OF MAN

U.S. SCULPTURE BETWEEN WAR

AND PEACE, 19451975

ROBERT SLIFKIN

_____________________________________

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

For Amos, wily prophet

Copyright 2019 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustration by Mike Reddy, based on Robert Smithson, Partially Buried Woodshed, 1970.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-19252-9

eISBN (ebook): 978-0-691-19426-4

Version 1.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019930956

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Designed by Jeff Wincapaw

CONTENTS

_________________________________________________________

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

_________________________________________________________

This book is the product of many years of reading, writing, looking, thinking, and talking. And while the majority of the reading and writing was a solitary affair, I am extremely grateful for the conversations and company of numerous friends and colleagues whose intelligence and encouragement kept me inspired and whose criticism and erudition kept me on the right track. Jay Curley, Hal Foster, Mark Haxthausen, Frank Heath, Alex Kitnick, Denise Lassaw, Meredith Martin, Alex Nemerov, Alex Potts, Jennifer Roberts, Sara Jane Roszak, Lytle Shaw, Rebecca Smith, and Marin Sullivan were especially crucial interlocutors; each read portions of the manuscript and provided valuable feedback that has critically shaped the final project. I am equally grateful for my colleagues and students at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University who have steadily challenged and stimulated me and have provided a supportive and congenial environment to work and think. In particular Pat Rubin and Michele Marincola suggested genial advice in our occasional chapter meetings, Anne Wheeler shared her expertise on Robert Smithsons archives, and Tom Crow offered sage insights on a range of subjects, both low and high.

I was fortunate to have the support of a number of institutions, many of which provided not only financial support but also collegiality and inspiring locations. My research was deeply enriched by my time at three institutions: The Henry Moore Institute in Leeds where Jon Wood shared his expert insights about modern sculpture; at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where the equally extraordinary library and scenery took my research to places I did not expect; and at the NYU Research Institute in Athens, where the opportunity to study classical statuary and architecture pushed me to think about the broader traditions of monumentality. A fellowship from the Hauser and Wirth Institute provided the opportunity to spend significant time in the archives of the David Smith Estate in New York where Susan Cooke, Tracee Ng, Rebecca and Candida Smith, and Peter Stevens all generously shared their knowledge.

Earlier versions of appeared respectively in the journal American Art and the Terra Foundation book Experience (2107), and I am grateful to the publishers and editors at these volumes for their support and critical feedback.

Two people made the inevitably laborious nature of writing this book much less onerous: Michelle Komie who expertly navigated the manuscript to its final form and Sam Allen who deftly tracked down images and prized reasonable licensing agreements from the local authorities.

Mike Reddy, whose witty and evocative illustrations appear at the beginning of each chapter, was an ideal collaborator.

And finally, I want to thank my family, Amanda and Amos, who, as the song goes, were there for the lowest lows and most of the highs that rocked this deadline chaser.

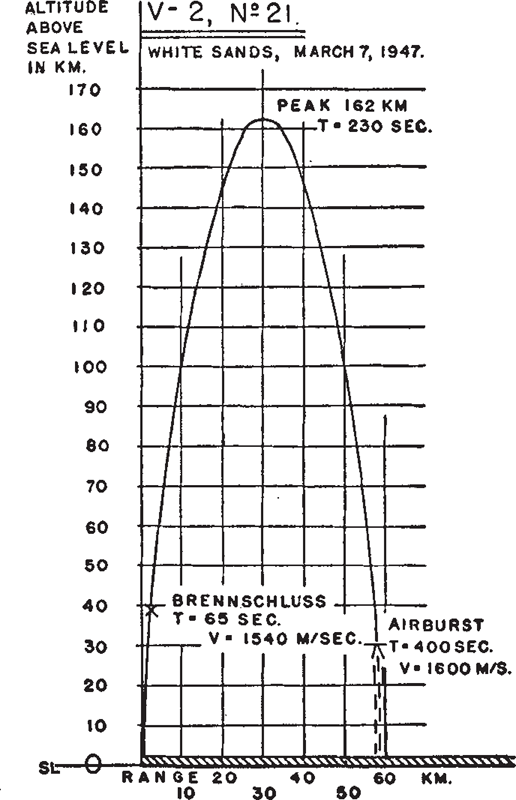

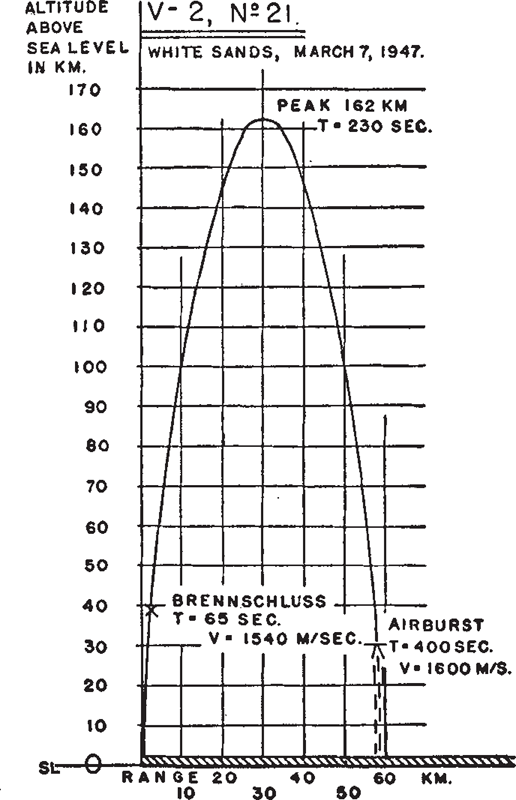

TRAJECTORY OF V2 ROCKET

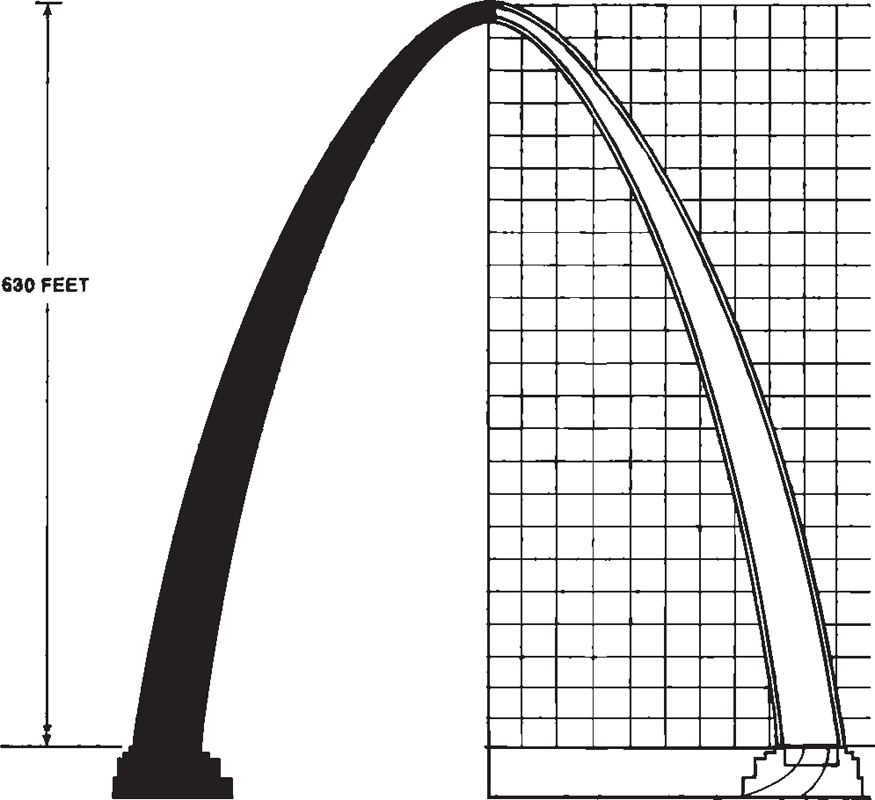

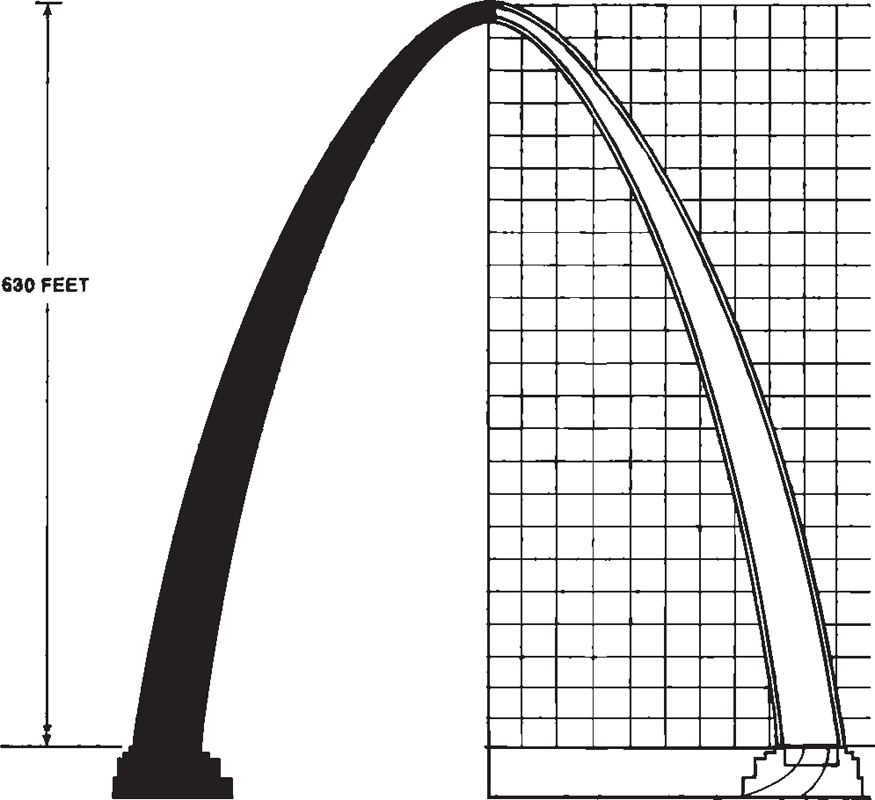

JEFFERSON NATIONAL EXPANSION MEMORIAL (GATEWAY ARCH) F. 53

INTRODUCTION

MONUMENTALISM AND METHOD

_________________________________________________________

Everything cannot be so easily grasped and conveyed as we are generally led to believe; most events are unconveyable and come to pass in a space that no word has ever penetrated; more unconveyable than all else are art-works, whose mysterious existences, whose lives run alongside ours, which perishes, whereas theirs endure.

RAINER MARIA RILKE , Letters to a Young Poet

The only relation to art that can be sanctioned in a reality that stands under the constant threat of catastrophe is one that treats works of art with the same deadly seriousness that characterizes the world today.

THEODOR ADORNO , Valry Proust Museum

This book describes how a significant strand of visual art produced in the United States in the years between 1945 and 1975 responded to the perils and promises of technology at a moment when, as President Dwight D. Eisenhower described it in his farewell address on January 17, 1961, it appeared that the growing power of a military-industrial complex threatened to fundamentally corrupt the nations politics, if not the very structure of our society.

This new phase of technological development, while certainly exhibiting the archetypal dilemmas of the Faustian bargain and the modern Prometheus, was arguably singular in its apocalyptic potential. There was a sense that humanitys relationship to the natural world had been irrevocably changed and that the future would never be the same, whether that meant that mankind would no longer be beholden to the limited resources of the planet or that humanity would destroy itself and its environment, or at least return either or both to an almost elemental, if not primordial, existence. The truly world-historical implications heralded by the dawn of the nuclear era for both peaceful and militaristic ends were not only articulated by presidents but suffused nearly all realms of existence in postwar American society, bringing, as Tom Vanderbilt puts it in his vibrant account of Cold War survival culture, the tremors of an unrealized war into the textures of everyday life.

In the way that it posed more problems than it could possibly solve, the atomic bomb was something of a perverse philosophical object, making questions of fate, free will, and humanitys relationship to its environment a matter of life and death. Along with numerous social scientists and philosophers, many artists and writers in the immediate postwar years sought to address the existential consequences foretold by the bomb. William Faulkner, in his 1950 Nobel lecture, declared that our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only one question: When will I be blown up?

Such explicit references to the bomb by artists and writers in the years following the end of the war were quite common. A number of critics and scholars in the ensuing years have considered the ways in which postwar visual art reflected and responded to this momentous matter, whether in terms of expressive imagery, as in the Pollocks cosmic vortexes or Adolph Gottliebs avowed blasts or in more allegorical portrayals of the ravages of war by artists such as Philip Evergood or Isamu Noguchi, or in the even more explicit antiwar imagery artists like Nancy Spero or Ed Kienholz began to employ in the 1960s as the country became increasingly mired in a seemingly unwinnable war in Vietnam (that was largely waged as a limited war meant to prevent all out nuclear war between the world superpowers).).