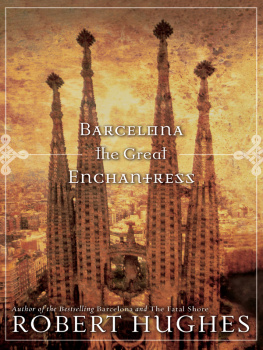

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

Copyright 1987, 1988, 1990 by Robert Hughes All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

The New York Review of Books: Seven essays by Robert Hughes.

Copyright 1978, 1979, 1982, 1984, 1989 by Nyrev Inc.

Reprinted by permission of The New York Review of Books.

The Time Inc. Magazine Company: All pre-1989 essays from Time Magazine by Robert Hughes copyright Time Warner Inc.; all 1989 essays from Time Magazine by Robert Hughes copyright The Time Inc. Magazine Company. Reprinted by permission.

D ESDEMONA . What wouldst thou write of me, if thou shouldst praise me?

I AGO . O gentle lady, do not put me to t, For I am nothing if not critical.

D ESDEMONA . Come on, assay.

Othello

Contents

Introduction: The Decline of

the City of Mahagonny

I

In the early 1960s, when I was a baby critic in Australia, it seemed that faraway New York had become a truly imperial culture, heir to Rome and Paris, setting the norms of discourse for the rest of the worlds art. This sense of imperial role (and the nervousness it induced in the provinces) would much later be summed up by Irving Sandler in the title of his fine book on Abstract Expressionism, The Triumph of American Painting.

Between 1945 and 1970, the quarter-century that saw the rise and flowering of the New York School, three generations of remarkable painters and sculptors seemed to have taken centrality away from Europe. First there had been the Abstract Expressionists: Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko, Newman, David Smith, Gorky, Guston, Krasner and Motherwell. Then there were the slightly younger painters whom Clement Greenberg and his school had nominated as the continuers of art history, the ones on whom the future of painting as a high art was alleged (wrongly, as it turned out) to depend: Noland, Olitski, Frankenthaler and especially Louis. And then the younger men and a few women who rose at the beginning of the 1960s, Johns and Rauschenberg, followed by Oldenburg, Lichtenstein, Rosenquist, Warhol, Kelly, Stella, Judd, Smithson, Morris, di Suvero, Serra; from there one could make up ones own list, which by the end of the 1970s might well have included painters such as Susan Rothenberg and Brice Marden and sculptors such as Joel Shapiro. And of course, Philip Guston againreborn, since 1968, as a figurative artist of extraordinary power.

It would be foolish to claim that 194570 in New York rivaled 18701914 in Paris. America has never produced an artist to rival Picasso or Matisse, or an art movement with the immense resonance of Cubism. But marvelous work was done there nevertheless. And it can certainly be said of the New York School that its artists often showed those native qualities listed by Frederick Jackson Turner in his history of the American frontier, qualities that seem inseparable from a younger America and are looked back on with nostalgia by Americans now: that coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness, that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients that restless, nervous energy, that dominant individualism and withal that buoyancy and exuberance.

One saw this triumph from afar, going down Fifty-seventh Street with its tramping legions and subjugated Gauls, its gold and purple and apotropaic cries. In Australia ones response to it came out as a sighresignation to ones own cultural irrelevance. We were already used to that, since for most of the two-hundred-year history of white Australia the colonial experience had bitten deeply into us and caused a reflex known as the Cultural Cringe.

The Cultural Cringe is the assumption that whatever you do in the field of writing, painting, sculpture, architecture, film, dance or theater is of unknown value until it is judged by people outside your own society. It is the reflex of the kid with low self-esteem hoping that his work will please the implacable father but secretly despairing that it can. The essence of cultural colonialism is that you demand of yourself that your work measure up to standards that cannot be shared or debated where you live. By the manipulation of such standards almost anything can be seen to fail, no matter what sense of finesse, awareness and delight it may produce in its actual setting.

There is no tyranny like the tyranny of the unseen masterpiece. That was our predicament. In Australia we had art schools teaching people how to make Czannes, but our museums had no real Czannes to show us. The seen and fully experienced masterpiece tends to liberate. Great art is seldom repressive. But reproduction is to aesthetic awareness what telephone sex is to sex: in Australia, without knowing it, we were anticipating that worthless freedom from the original art object, the sense of floating among its media clones, which would be so lauded in 1980s New York as part of the postmodernist experience. It was stifling to independent judgment. There have been fine painters in Australia, at least since the rise of its Impressionist school in the 1880s. One can very well imagine an alternative history of twentieth-century art with some Australian artists in it, Arthur Boyd, for instance, or Fred Williams. But we Australians tended to be afraid to claim our own qualities, for fear of looking gauchenot just to others but to ourselves as well. Much the same thing had happened earlier in the United States, of course. Few people today would dispute that Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer were among the greatest of nineteenth-century realists. Very few Americans wanted to believe that thirty years ago, for fear of being judged provincial by other, Francophile Americans. In Australia, for fear of seeming unsophisticated, we kept wondering: Is this up to international standards? And we had no answer, because we could not articulate these standards for ourselves. In this we may not have been so different from most American artists living out of easy reach of New York in the fifties and sixties.

Thirty years ago, Abstract Expressionism was pretty well a mandatory world style. We in Australia looked at it with awe. The bottle in which its messages washed up on our shores (since the paintings themselves did not cross the Pacific) was the magazine