Table of Contents

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781407054070

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Vintage 2003

Copyright Robert Hughes 1986

Maps copyright Raphael Palacios 1986

Robert Hughes has asserted his right under the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author

of this work

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

First published in Great Britain in by

Collins Harvill in 1987

Vintage

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

www.vintage-books.co.uk

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group

Limited can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780099448549

The Random House Group Limited supports The Forest

Stewardship Council (FSC), the leading international forest

certification organisation. All our titles that are printed on

Greenpeace approved FSC certified paper carry the FSC logo.

Our paper procurement policy can be found at

www.rbooks.co.uk/environment.

Printed in the UK by CPI Bookmarque, Croydon, CR0 4TD

About the Author

Robert Hughes, art critic of Time magazine and twice winner of the American College Art Associations F.J. Mather Award for distinguished criticism, is author of The Shock of the New, and of Heaven and Hell in Western Art. He is also the author of the acclaimed Nothing If Not Critical, criticism at its most intelligent and impressive, trenchant, lucid, elegantly written... in the words of William Boyd; a work on Frank Auerbach; Barcelona, Culture of Complaint, essays on the fraying of America, described in the Observer as the most bracing of critical broadsides against new anti-intellectual tyrannies, and Things I Didnt Know.

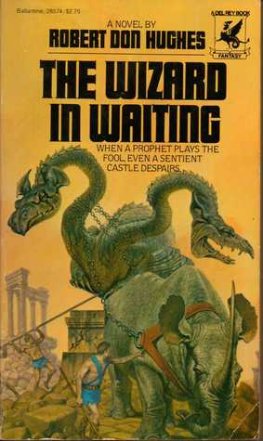

ALSO BY ROBERT HUGHES

The Art of Australia

Heaven and Hell in Western Art

The Shock of the New

Lucien Freud

Frank Auerbach

Nothing If Not Critical:

Selected Essays on Art and Artists

Barcelona

Culture of Complaint:

The Fraying of America

Things I Didnt Know

For my godson

ALEXANDER BLIGH TURNBULL , B . 1982

a seventh-generation Australian

and for my sons godparents

ALAN MOOREHEAD , 19101983

LUCY MOOREHEAD , 19081979

che n la mente me fitta, e or maccora,

la cara e buona imagine paterna

di voi...

e quantio labbia in grado, mentrio vivo,

convien che nella mia lingua si scerna.

Dante, Inferno, XV, 8287

I have been studying how I may compare

This prison where I live unto the world:

And, for because the world is populous,

And here is not a creature but myself,

I cannot do it;yet Ill hammert out.

Shakespeare, Richard II, V. v.

The very day we landed upon the Fatal Shore,

The planters stood around us, full twenty score or more;

They ranked us up like horses and sold us out of hand,

They chained us up to pull the plough, upon Van Diemens Land.

Convict ballad, ca. 182530.

Contents

Introduction

T HE IDEA for this book occurred to me in 1974, when I was working on a series of television documentaries about Australian art. On location in Port Arthur, among the ruins of the great penitentiary and its out-buildings, I realized that like nearly all other Australians I knew little about the convict past of my own country.

I grew up with a skimpy sense of colonial Australia. Convict history was ignored in schools and little taught in universitiesindeed, the idea that the convicts might have a history worth telling was foreign to Australians in the 1950s and 1960s. Even in the mid-1970s only one general history of the System (as transportation, assignment and secondary punishment in colonial Australia were loosely called) was in print: A. G. L. Shaws pioneering study Convicts and the Colonies. An unstated bias rooted deep in Australian life seemed to wish that real Australian history had begun with Australian respectabilitywith the flood of money from gold and wool, the opening of the continent, the creation of an Australian middle class. Behind the bright diorama of Australia Felix lurked the convicts, some 160,000 of them, clanking their fetters in the penumbral darkness. But on the feelings and experiences of these men and women, little was written. They were statistics, absences and finally embarrassments.

This sublimation has a long history; the desire to forget about our felon origins began with the origins themselves. To call a convict a convict in early colonial Australia was an insult certain to raise colonial hackles. The approved euphemism was Government man. What the convict system bequeathed to later Australian generations was not the sturdy, skeptical independence on which, with gradually waning justification, we pride ourselves, but an intense concern with social and political respectability. The idea of the convict stain, a moral blot soaked into our fabric, dominated all argument about Australian selfhood by the 1840s and was the main rhetorical figure used in the movement to abolish transportation. Its leaders called for abolition, not in the name of an independent Australia, but as Britons who felt their decency impugned by the survival of convictry. They were transplanted Britons but Britons still, plus royalistes que la reine. The first signs of Australian social identity had appeared as early as the 1820s among the Currency lads and lasses, most of whom were native-born children of former convicts. In the name of abolition, this picture had to be severely edited in the 1840s; and for decades to come, the official voices of Australia would continue to stake their claim to respectability on their Britishness. If the end of transportation had been brought about in the name of the convicts own descendants, this might not have happened. But the fight was on behalf of free emigrants and their stock; it was this side of Australia which most fervently brandished the myth of corrupted blood and convict evil. After abolition, you could (silently) reproach your forebears for being convicts. You could not take pride in them, or reproach England for treating them as it did. The cure for this excruciating colonial double bind was amnesiaa national pact of silence. Yet the Stain would not go away: the late nineteenth century was a flourishing time for biological determinism, for notions of purity of race and stock, and few respectable native-born Australians had the confidence not to quail when real Englishmen spoke of their convict heritage.