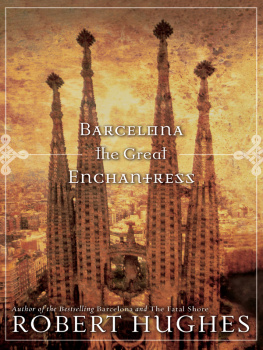

B ARCELONA

the Great

E NCHANTRESS

R OBERT H UGHES

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC DIRECTIONS

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

Washington, D.C.

Published by the National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-4688

Text copyright 2004 Robert Hughes

Map copyright 2004 National Geographic Society

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the National Geographic Society.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hughes, Robert, 1938

Barcelona, the Great Enchantress / Robert Hughes.

p. cm. (National Geographic directions)

ISBN: 978-1-4262-0913-0

1. Barcelona (Spain)Civilization. 2. Barcelona (Spain)Description and travel. 3. Hughes, Robert, 1938-Homes and hauntsSpainBarcelona. 4. Arts, SpanishSpainBarcelona. 5. Architecture SpainBarcelona. 6. Barcelona (Spain)Buildings, structures, etc. I. Title. II. Series.

DP402.B265H87 2004

946'.72dc22

2004006082

One of the worlds largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations, the National Geographic Society was founded in 1888 for the increase and diffusion of geographic knowledge. Fulfilling this mission, the Society educates and inspires millions every day through its magazines, books, television programs, videos, maps and atlases, research grants, the National Geographic Bee, teacher workshops, and innovative classroom materials. The Society is supported through membership dues, charitable gifts, and income from the sale of its educational products. This support is vital to National Geographics mission to increase global understanding and promote conservation of our planet through exploration, research, and education.

For more information, please call 1-800-NGS LINE (647-5463), write to the Society at the above address, or visit the Societys Web site at www.nationalgeographic.com.

To Daisy, who loves the highest

when she sees it.

B ARCELONA the G REAT E NCHANTRESS

CONTENTS

ONE

I FIRST WENT TO B ARCELONA NEARLY FOUR DECADES AGO, in 1966. This happened because I was an opinionated and poorly informed loudmouth. I spoke little Spanish and no Catalan, but at a party in London, under the influence of various stimulants, I had been holding forth on the subject of the great and long-dead Catalan architect Antoni Gaud. I had some theories, entirely cribbed from French writers, about the surrealist affinities of Gauds work. (In fact it has no surrealist affinities of any discernible kind. Indeed it is utterly and fundamentally opposed to everything the surrealists believed in and tried to propagate, but well, hell, it was the swinging sixties in London and you didnt need proof. Bullshit would do.) As I warmed to my theme, or themes, if you could call them that, I observed that a foreign-looking man was watching me and listening, quizzically. He was youngish, but older than me, about thirty. He was very close shaven but had the swarthy look of a Gypsy. His pomaded hair, long at the back, curled somewhat greasily over a stiffish and striped collar. He had a brown suit, tobacco colored and of extreme though somehow dated elegance, the jacket tubular and tightly buttoned, in the utmost contrast to the flowing and flopping garments or patched self-embroidered jeans worn by the other men in the room. A handmade Turkish handkerchief hung negligently from his breast pocket. His shirt was formal and his shoes had clearly been handmade, too, smoothly encasing his small and birdlike feet like shining purses. He was smoking an unfiltered Playersabout the fiftieth of the day, I would later come to realize.

It is good to meet a fan of Gaud in England, he said in a dense growling accent, even if you know so little about him.

And this was how I came to meet the man who before the evening was out became my friend, and forty years later is still my dearest and oldest one: the Catalan sculptor Xavier Corber. Xavier forgave me for prating about a subject of which I knew nothing, since I could hardly be blamed for not having been to Barcelona. Very few people have, he said, a trifle dismissively, implying that the world is full of fools anyway. But he was not going to let me continue to be a fool, and the only way around that was to ensure that I should actually see the works of Gaud, not just the Sagrada Famliathe unfinished temple that everyone mentioned as the epitome of his work, but which in his view was by no means its summabut a number of other buildings by him as well. He reeled off their names in his sharply clacking Catalan accent, leaving me quite nonplussed: I might call myself an art critic, and in point of fact I did, but I had never heard of any of them. The same for the various other Catalan architects of the art nouveau period (about 1870-1920) whose names Xavier let fall, and the artists, and so on and so forth. Clearly, there was a whole bunch of stuff just down there, under the shadow of the Pyrenees, of which I was quite virginally ignorant. And Xavier wanted me to know about it; not in the spirit of an art dealer promoting his fondest find, but because, as a serious Catalana creature not to be confused with a normal Spaniardhe could not endure the spectacle of someone elses ignorance of his own patria chica.

So I went. And shortly afterward, returned. And then, the next spring, went again. I was hooked and couldnt stay away. Once I lived in a peculiar, once grand but now somewhat ramshackle hotel at the foot of the road up whose middle the electric tramway ran, clattering and groaning, to Tibidabo, the vantage point from which the whole plain of Barcelona could be seen spreading below; this hotel, though much lower than Tibidabo, had a domed mirador on the roof sumptuously ornamented with 1900-style mosaics, in which one could sit, look at the city, and dream on a hot day. It seemed to have no other clients (at least I never saw one) and its room rate was somewhat less than ten dollars a day. The bed sagged and the faucet spat a thin stream of boiling brown water. It was, I thought, heaven.

But mostly I stayed in Xaviers house. It was not in town. It was a country masia, in a village named Espluges de Llobregat, which had not yet been absorbed by the southerly expansion of Barcelona itself. (Today it almost has, but Xavier owns most of the cobbled street the home stands in, so the place is in no danger. Its just a completely unexpected, and unpredictable, oasis of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the middle of the twenty-firsta time warp in brick and stucco.) Named the Can Cargol (House of the Snail), it stands on a back road above the village. Espluges in Catalan means cavesit comes from the Latin speluncas and that is what the Can Cargol has in its basement: an extended, twisting series of grottoes dug deep into the hillside for reasons of storage and, perhaps originally, defense, by farmers who owned the area in Roman times. Possibly these subterranean windings reminded people of the secret labyrinth of a snail shell, and so named the house. But even when I was staying in the Can Cargol in the 60s, I never ventured to properly explore these catacombs, being cravenly afraid of spiders and darkness. Only God, or perhaps Pluto, deity of the underworld, knows with any certainty what is down there. One of the caves has, or at least had, an enormous printing press in it, a greasy dusty Moloch of a machine dating from the mid-nineteenth century, on which some long-dead radical Catalanist may well have run off anti-Carlist tracts in bygone days. For years Xavier and his friends, including myself, drank an excellent red wine of which someone in Penedes had given him hundreds of bottles: Since he had not bothered to have storage racks made, those bottles were simply dumped, higgledy-piggledy, on the earthen floor of the catacomb, where their labels were nibbled away to illegibility over the years by rats, mold, and insects.