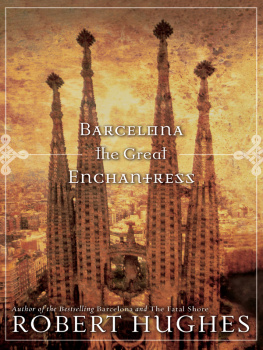

ACCLAIM FOR

Robert Hughess

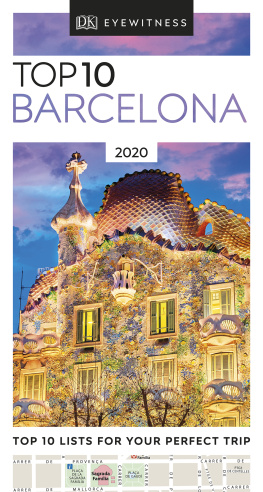

BARCELONA

For those interested in epic storytelling, captivating characters, and authoritative insights, Barcelona has no real competition. Hughes leads readers on an enlightening and sophisticated cultural journey that will illuminate the citys history.

San Francisco Chronicle

Lavish Hughes sees deeply and meticulously [and] his feel for the texture of things [is] acute a tribute that could hardly be better rendered.

Chicago Tribune

Hughes can move commandingly from a Mir canvas to transvestite hookers in the street without missing a beatand bring to both the same kind of rigorous attention and full-bodied sensibility. The text is enlivened at every turn by mischievous erudition, rococo diction, and Augustan bite.

Time

Truly majestic The city is lucky to be commemorated by so formidable a chronicler. [A] cornucopia of facts, evocations, interpretations and speculations, presented with a grand enthusiasm immense range, variety, and exuberance.

Jan Morris, Los Angeles Times

Hughes is a writer of such virtuosity that he could make a mattress tag lively reading. He has sketched a portrait of the city and its 2,000-year history with such brio that one comes to think of it as a person. His writing is a species of engaging highbrow hip-hopgreat fun in itself. His kinetic prose is a performance.

Christian Science Monitor

Also by Robert Hughes

Rome (2011)

Things I Didnt Know (2006)

Goya (2003)

American Visions (1997)

The Culture of Complaint (1993)

Nothing If Not Critical (1990)

Frank Auerbach (1990)

Lucian Freud (1988)

The Fatal Shore (1987)

The Shock of the New (1981, 1991)

Heaven and Hell in Western Art (1969)

The Art of Australia (1966)

Robert Hughes

BARCELONA

Robert Hughes was born in Australia in 1938 and after 1964 lived in Europe and the United States. He worked in New York as art critic for Time magazine until 2001. His books include The Art of Australia (1966); Heaven and Hell in Western Art (1969); The Shock of the New (1981, 1991); The Fatal Shore (1987), winner of both the W. H. Smith Prize and the Duff Cooper Award; a collection of essays on art and artists, Nothing If Not Critical (1990); and Frank Auerbach (1990). He twice received the Franklin Jewett Mather Award for Distinguished Criticism from the College Art Association of America, and in 1991 was made an Officer in the Order of Australia. He died in 2012.

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, MARCH 1993

Copyright 1992 by Robert Hughes

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1992.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hughes, Robert, 1938 Barcelona / Robert Hughes.1st Vintage Books ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-307-76461-4

1. Barcelona (Spain)Civilization. 2. Barcelona (Spain)Buildings, structures, etc. 3. Arts, SpanishSpainBarcelona. 4. ArchitectureSpainBarcelona. I. Title.

DP402.B265H86 1992

946.72dc20 92-56349

Author photograph Joyce Ravid

v3.1_r1

For Xavier and Maria-Luisa Corber

CONTENTS

PREFACE

This book was meant to be thinner. My original intent, in 1987, was to write an account of the modernista or Art Nouveau period (roughly, 18751910) in Barcelona, concentrating on its architecture, as a companion for visitors to the city.

This notion changed. It would have meant examining the foliage of the tree without considering its trunk and roots. So much of what was built in Barcelona in the late nineteenth century was grounded in a strong, even obsessive, sense of the Catalan past, in particular its medieval past, that there was little point in trying to describe the newer without the older. Moreover, the desire to revive the glories of the Catalan middle ages, felt so strongly by the architects of Barcelonas fin de sicle, was also shared by writers, painters, and sculptors, and deeply entwined with the issues of political independence from Madrid and a sense of cultural continuity expressed in the struggle for the Catalan language.

It is a truism that all cities are shaped by politics. But it is true neverthelessand true, to a spectacular and insistent degree, of Barcelona. To take only the Catalan architect everyone has heard of, Antoni Gaud: his work is hard to read until one grasps not only his sense of a specifically Catalan past, but his convictions about Catalan autonomy and his intense and patriarchal religious conservatism as well. In such matters lies the clue to why his rich patrons, notably Eusebi Gell, employed him: not just because he was an architect of genius, but because his ideology fitted theirs. The political and economic history of Barcelona is written all over its plan and buildings, and one cannot begin to understand Catalan architectureparticularly that of the nineteenth century, when it was such a forceful expression of national aspirationwithout the image bank of local identity that lay behind it and often makes sense of what the foreign visitor is apt, at first, to assign to mere fantasy.

The time span of the book is nearly two thousand years, from the emergence of Barcelona as a tiny Augustan colony in the first century A.D . to the death of Gaud in 1926. It treats the Roman, Visigothic, Moorish, and Frankish periods of the citysay, to about 900 A.D .very sketchily. Its period is the thousand years after that, and its main concentration is on the city in the second half of the nineteenth and the first quarter of the twentieth century. I refer to some of the urbanistic and cultural results of the Franco years (193975) in the first chapter, but I have made no attempt to deal with the Republic and the civil war at all, since it is the one decade in Barcelonas history that is exhaustively covered by non-Spanish historiansand it requires, in any case, skills I do not have.

The coming decade, it seems, will see the final winding-up of the model of cultural activity that served modernism so well, one that it inherited from papal Rome and seventeenth- to nineteenth-century Paris: the idea of the central city dictating its norms to the provinces and colonies. Probably the last city to assume that role in culture was New York, whose heyday lasted from about 1925 to 1975. In a postimperial world sundered by irrepressible nationalisms, and in a Europe whereirony of ironiesnationalist fervor, often of an ugly and racist kind, is once more on the rise even as the structures of European unification are bolted into place, the focus of cultural interest seems bound to follow the political shift and address itself to the local, the particular, the non-mainstream. In writing about Barcelona, I wanted to write about a culture that was, from the point of view of the larger capitals, provincial. (No doubt this was involved, on a none-too-subliminal level, with the fact that I am a provincial, an Australian.) Even though the issue of Catalan political separatism was repudiated by its own State government in September 1991 and now seems politically dead except among a few nostalgists and rhetoricians (it could hardly be expected to survive the real democratic changes of Spain after 1975), the sense of Catalunya as a distinct cultural entity within the larger Iberian body endures. It has been a source of great strengthand, occasionally, of self-delusion as wellfor writers, architects, and artists, many of whom viewed their own creative efforts as rebuttals of centralism; and its results have often transcended centralist ideas of the merely local.