Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves

Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves

RACE, WAR, AND MONUMENT IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICA

New Edition

KIRK SAVAGE

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 1997 by Princeton University Press

Preface to the new paperback reissue copyright

2018 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

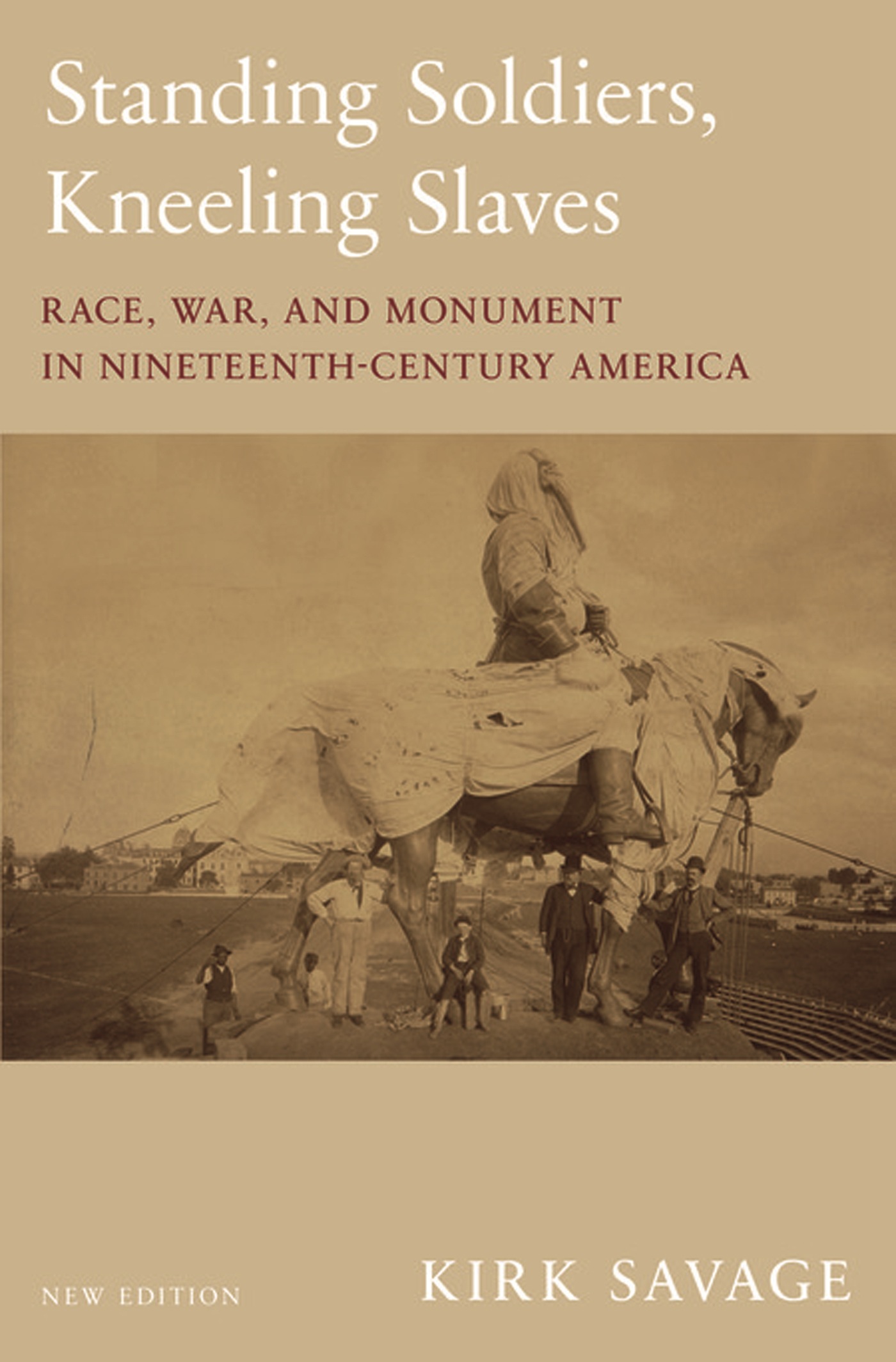

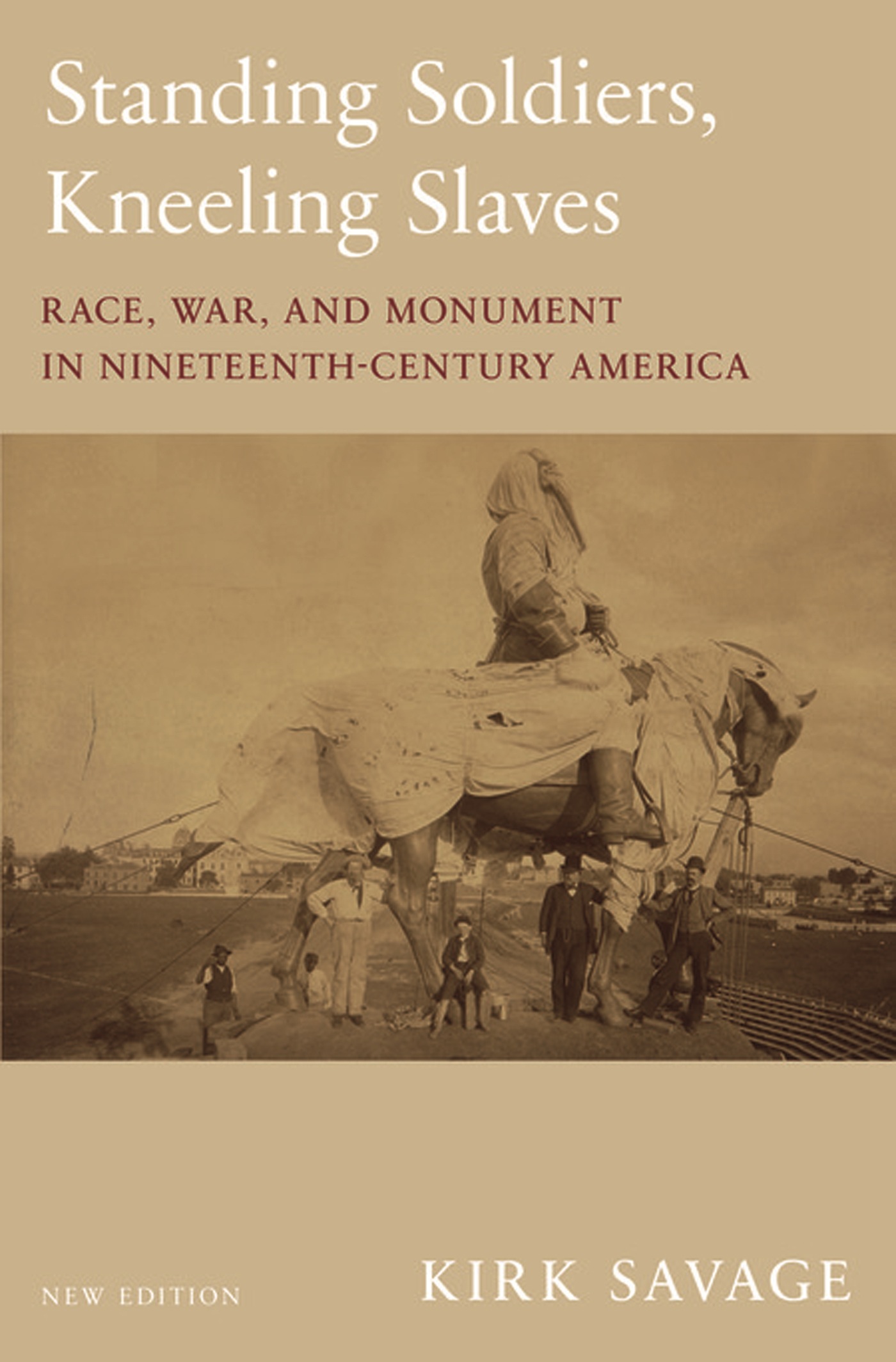

Cover image: Photograph after hoisting of the Lee statue, May 29, 1890.

American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Va.

All Rights Reserved

First paperback printing, 1999

Paperback reissue, with a new preface by the author, 2018

ISBN (pbk.) 978-0-691-18315-2

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows Savage, Kirk, 1958

Standing soldiers, kneeling slaves : race, war, and monument in nineteenth-century America / Kirk Savage.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-01616-0 (alk. paper)

1. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Social aspects. 2. SlavesEmancipationUnited States. 3. Public sculptureUnited StatesHistory19th century. 4. United StatesRace relations. 5. National characteristics, AmericanHistory19th century. I. Title.

E468.9.S28 1997

973.71dc21 97-9731

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Eli, Charlotte, Rose, Sara, and Elizabeth

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE NEW EDITION

IN THE SPRING OF 1890, John Mitchell, the fiery twenty-six year old editor of the black newspaper The Richmond Planet, made sure that his paper covered the dedication of Richmonds majestic monument to Robert E. Lee, notable as the first heroic equestrian statue of a Confederate erected anywhere in the United States. Mitchell had been born enslaved in Richmond during the war fought by Lee and the Confederacy to keep him and his people in bondage. Shortly after the statues unveiling, he wrote, The Negro put up the Lee Monument, and should the time come, will be there to take it down.

Remarkably, that time has now come. While Richmonds own Monument Avenue so far has escaped the removal cranes, they have been active elsewhere across the United States. At this writing, Confederate busts, statues, obelisks, fountains, and markers have come down in a couple of dozen towns and cities in the old states of the Confederacy and even as far afield as California, Missouri, Montana, and New York. Charlottesvilles huge equestrian statues have been shrouded. The Lee and Jackson windows in Washingtons National Cathedral have been removed. Most of these memorials honored political leaders and military commanders, but even ordinary Confederate soldier monuments have fallen by the hands of authorized crews or the ropes of angry crowds.

Until recently, almost no one but Mitchell had anticipated this outcome. When Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves first appeared in the 1990s, the neo-Confederate movement was still in full swing. Confederate statues were being lovingly restored and sometimes even rededicated with new ceremonies. The idea that these monuments had been designed and built to promote white supremacy was often dismissed but most of the time simply ignored. Today that idea has become mainstream, discussed in newspapers and websites and talk shows. Now the defenders of Confederate monuments have largely abandoned the ideological fight and retreated to a seemingly neutral defense of history. Like it or not, they say, these monuments represent our history. Removing them, therefore, is an act of historical erasure.

If there is one lesson to be learned from studying how monuments get chosen and built, it is that they most certainly do not represent history in any straightforward or responsible way. They represent the agendas, obsessions, prejudices, whims, and, occasionally, the high ideals and aspirations of those people in society who happened to have the power to erect them in public. The resulting commemorative landscapes are highly politicized, and often bizarre, assemblages of historical characters many of whom have been long forgotten, sometimes deservedly so.

And yet these landscapes and the monuments in them have their own histories that are enormously revealing and absolutely worth studying. Even if monuments pretend to be permanent, eternal, and staticin other words, outside historythey have always been prey to the historical forces that gave them birth, changed the world around them, and sometimes even destroyed them.

A crucial piece of this history, often overlooked, is the monuments that might have been, but never came to be. At one time these were ideas, seeds, and sometimes elaborately developed schemas for alternative histories. They held possibilities that were later erased by the very success of those monuments that managed to rise in their stead, as Lee did on Monument Avenue.

The suppression of those alternative monumentsthat parallel universe of possibilityamounted to nothing less than a preemptive erasure of the past. Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves recounts one of the most dramatic stories of preemptive erasure, with consequences that continue to reverberate over a century later. In the wake of the Civil War, with the United States abruptly and unexpectedly free of slavery, the nation had a unique opportunity to retell its past: to reckon with the crime of slavery, to honor the formerly enslaved people in the story of their own liberation, and to make room for them, finally, as full-fledged and necessary participants in the moral awakening of America. In the main, none of this came to pass; the commemorative landscape took an entirely different turn. It was a failure of artistic imagination and of political will, a failure at all levels to relinquish the hold of white supremacy. And that was a tragedy as well, because the erasure of alternative pasts is also, always, an erasure of alternative futures. Monuments are as much about the future as the past.

Instead the commemorative landscape became dominated by men in military uniformnot only commanders like Lee, but, for the first time, ordinary anonymous soldiers, whose statues spread across the country into cities and small towns, some of which had never before had a single piece of public sculpture. Yet almost nowhere in this vast outpouring of military monuments did black soldiers get any recognition. The nearly 180,000 who enlisted in the Union Army had more at stake, and less reluctance, than anyone else in this conflict. Unlike their white counterparts, black soldiers were fighting for the most elemental cause of all, the right simply to be treated as human beings. Not until the close of the nineteenth century did a monument appear showing black soldiers in uniformthe singular memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts whose story closes this book.

Next page