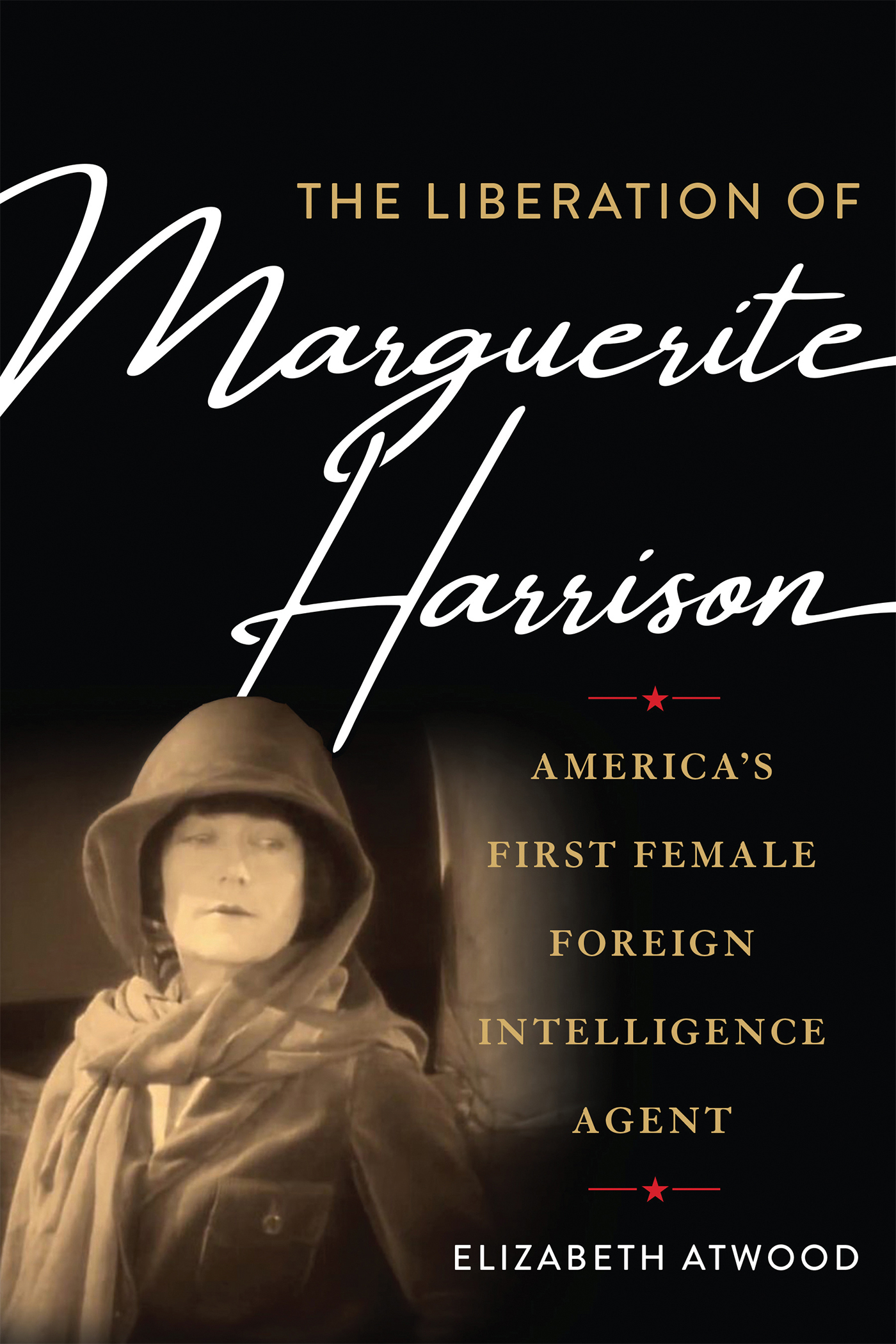

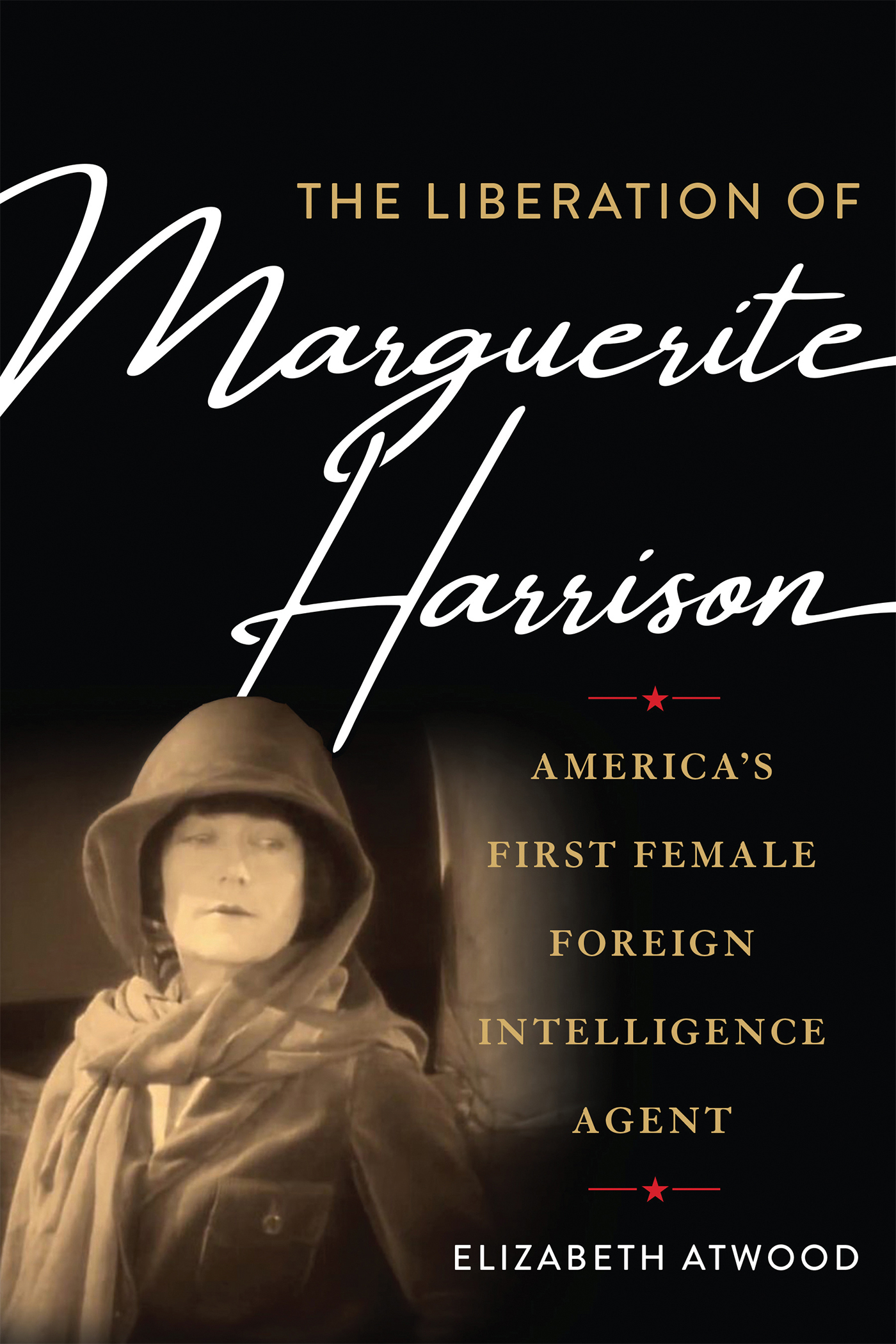

THE LIBERATION OF

Marguerite Harrison

THIS BOOK HAS BEEN BROUGHT TO PUBLICATION WITH THE GENEROUS ASSISTANCE OF EDWARD S. AND JOYCE I. MILLER.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2020 by Elizabeth Atwood

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Atwood, Elizabeth Ann, author.

Title: The liberation of Marguerite Harrison : Americas first female foreign intelligence agent / Elizabeth Atwood.

Other titles: Americas first female foreign intelligence agent

Description: Annapolis, Maryland : Naval Institute Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020009877 (print) | LCCN 2020009878 (ebook) | ISBN 9781682475270 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781682475300 (epub) | ISBN 9781682475300 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Harrison, Marguerite, 18791967. | United States. War Department. Military Intelligence DivisionHistory. | Espionage, AmericanGermanyHistory20th century. | Espionage, AmericanSoviet UnionHistory20th century. | Soviet UnionPolitics and government19171936. | SpiesUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Women intelligence officersUnited StatesBiography. | Intelligence officersUnited StatesBiography. | Baltimore (Md.)Biography.

Classification: LCC UB271.U5 A88 2020 (print) | LCC UB271.U5 (ebook) | DDC 327.12730092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020009877

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020009878

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Printed in the United States of America.

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 209 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First printing

For Andrew and Michael

Wishing them many happy adventures

CONTENTS

PREFACE

MARGUERITE ELTON BAKER HARRISON was born into a wealthy Baltimore family during the Victorian era, when a womans status was determined by her family and her life revolved around her husband and children. And so it was with Harrisonat least until her husbands sudden death in 1915 upended her world. For the next ten years she sought solace from her grief and freedom from societal expectations, first as a newspaper reporter and then as an international spy. At the time she entered the Military Intelligence Division, American women could not vote for fear they would be corrupted by the unseemly business of government and politics. Nevertheless, Harrisons missions took her to dangerous streets in postwar Berlin, across frozen plains of Russia, and, ultimately, to the fetid cells of a Bolshevik prison.

In the numerous books, magazine articles, and newspaper stories that Harrison wrote about her adventures, she never mentioned that she was Americas first female foreign intelligence officer. This accomplishment was not something she would have found noteworthy because, for most of her life, Harrison was an ambivalent feminist. She did not publicly champion womens suffrage, birth control, or equality in the workplace. Raised as a woman of privilege, she saw no reason to advocate for womens rights. Wealth and connections opened doors. She founded a childrens hospital, worked as a newspaper reporter, and became an international spy with the help of family and friends. Only when she approached the age of fifty and founded a society for women explorers did Harrison embrace the feminist label and become a champion of womens equality. Even so, after she remarried in 1926, she quit the foreign service and ended her solo adventures in order to support her husbands acting career. When Harrison died in 1967, she left it to a new generation to fight for womens rights.

I first heard about Marguerite Harrison soon after I started work at the Baltimore Evening Sun in 1988. As someone who entered journalism just a few years after Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein helped bring down a president, I found the idea of a reporter working as a government spy disturbing, even scandalous.

As I learned more about the Baltimore socialite turned reporter and agent, I became intrigued by this unconventional and controversial woman. I discovered that she grew up in Catonsville, Maryland, the community where I live, and that she held a life-long fascination with Russia, the country where I researched my doctoral dissertation and met my husband. While I could never identify with her privileged upbringing or zest for reckless adventure, Marguerite Harrison and I shared many of the same interests.

In 2016 I resolved to learn everything I could about Harrison. This task was complicated by her having left no diary and few personal letters. Few of her intelligence reports have survived. In many cases the only accounts about events in her life are those she revealed in her autobiography, Theres Always Tomorrow: The Story of a Checkered Life. In her memoir she recounted growing up under the restrictions imposed by a domineering mother; her happy but brief marriage to a Baltimore stockbroker; her work at the Baltimore Sun; and her decision to become a spy at the end of World War I.

But digging deeper, I discovered that Harrison was less than forthcoming about many aspects of her life. At times she either misremembered or intentionally misstated events and circumstances, including the extent of her involvement with U.S. intelligence services. She hinted at her need to be circumspect when she told readers that she recognized the risk of espionage: If I succeeded, my efforts would never be publicly recognized. If I failed, I would be repudiated by my government and perhaps lose my life.

Harrison portrayed her intelligence work as a brief interlude in her career as a writer, but I uncovered evidence that her spying lasted much longer and was more involved than she revealed. Files in the National Archives show that she sent reports to the U.S. Army and State Department throughout her travels in the early 1920s. Most surprising was the discovery of a note scribbled in the corner of a letter revealing that a 1925 documentary she made with noted filmmakers Merian Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack was a cover for a spy mission to the Middle East.

The archival records gradually began to reveal a picture of Harrison very different from the image portrayed in her writings. Records show that Harrisons linguistic talents and familiarity with Europe persuaded officers in the U.S. Army to hire her as Americas first female foreign agent. Although women had spied during the American Revolution and Civil War, Harrison was the first to be dispatched overseas because of her knowledge and skills. She performed so well, she was entrusted with some of the nations most sensitive missions. She was among a handful of spies sent into Berlin to collect information on political and economic conditions while peace negotiations were under way in Versailles. With the rising threat of Bolshevism, she gathered evidence against suspected Socialists and Communists. She was dispatched to Russia to locate American prisoners and to collect information on the viability of Lenins government. And she was the United States eyes and ears in Japan, China, Siberia, and the Middle East where newly emerging American industry sought a foothold. The fact that she accomplished these missions when many Americans still believed women should not involve themselves in the sometimes dirty business of government and politics is testament to both her talents and the vision of the men who trusted her.

Next page

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).