THE LAST SPEAKERS

THE QUEST TO SAVE THE WORLDS MOST

ENDANGERED LANGUAGES

K. DAVID HARRISON

Published by the National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036

Copyright 2010 K. David Harrison. All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without

written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harrison, K. David.

The last speakers: the quest to save the worlds most endangered languages / K. David Harrison.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-1-4262-0668-9

1. Endangered languages. 2. Language attrition. 3. Language maintenance. 4. Linguistic change. 5. Linguistic minorities. 6. Sociolinguistics. I. Title.

P40.5.E53H37 2010

408.9dc22

2010014720

Contents page, Chris Rainier/National Geographic Enduring Voices Project;, , Courtesy of Swarthmore College Linguistics Department.

Photo insert: .

The National Geographic Society is one of the worlds largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations. Founded in 1888 to increase and diffuse geographic knowledge, the Society works to inspire people to care about the planet. It reaches more than 325 million people worldwide each month through its official journal, National Geographic, and other magazines; National Geographic Channel; television documentaries; music; radio; films; books; DVDs; maps; exhibitions; school publishing programs; interactive media; and merchandise. National Geographic has funded more than 9,000 scientific research, conservation and exploration projects and supports an education program combating geographic illiteracy.

For more information, please call 1-800-NGS LINE (647-5463) or write to the following address:

National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

Visit us online at www.nationalgeographic.com

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books

Subsidiary Rights: ngbookrights@ngs.org

For Khiem H. Tang

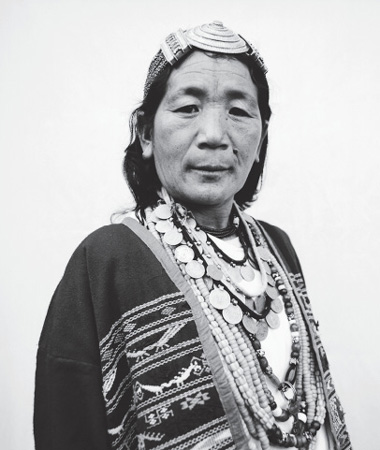

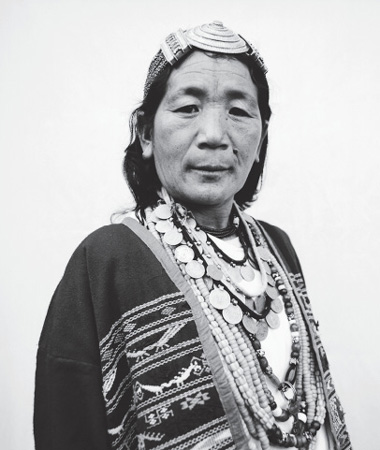

Koro speaker, near Bana village, Arunachal Pradesh, India

CONTENTS

Dying languages succumb

more discreetly. Village by village

they go underno shouting,

no watery ruckus.

Just a simple, sudden absence.

It takes a shrewd eye to spot

these silent catastrophes,

and a frugal, determined heart

to intervene.

John Goulet

{INTRODUCTION}

MY JOURNEY AS A SCIENTIST exploring the worlds vanishing languages has taken me from the Siberian forests to the Bolivian Altiplano, from a fast-food restaurant in Michigan to a trailer park in Utah. In all these places Ive listened to last speakersdignified elderswho hold in their minds a significant portion of humanitys intellectual wealth.

Though it belongs solely to them and has inestimable value to their people, they do not hoard it. They are often eager to share it, sometimes because they find so few of their own people willing to listen. What can we learn from these languages before they go extinct? And why should we lift a finger to help rescue them?

As the last speakers converse, they spin out individual strands of a vast web of knowledge, a noosphere of possibilities that encircles all of us. They tell how their ancestors calculated accurately the passing of seasons without clocks or calendars, how humans adapted to hostile environments from the Arctic to Amazonia.

We imagine eureka moments taking place in modern laboratories or in classical civilizations. But key insights of biology, pharmacology, genetics, and navigation arose and persisted solely by word of mouth, in small, unwritten tongues. This web of knowledge contains feats of human ingenuityepics, myths, ritualsthat celebrate and interpret our existence.

Pundits argue that linguistic differences are little more than random drift, minor variations in meaning and pronunciation that emerge over time (the British say lorry, Americans truck Tuesday is chooz-day for Brits, tooz-day for Americans).

These differences revealsome claimnothing unique about our souls or minds. But thats like saying that the Pyramid of Cheops differs from Notre Dame Cathedral only by stone-cutting techniques that evolved randomly in different times and places, revealing nothing unique in the ancient Egyptian or medieval French imagination.

All cultures encode their genius in verbal monuments, while considerably fewer do so in stone edifices. We might as well proclaim human history banal, and human genius of no value to our survival.

The fate of languages is interlinked with that of species, as they undergo parallel extinctions. Scientific knowledge is comparable for both domains, with an estimated 80 percent of plant and animal species unknown to science and 80 percent of languages yet to be documented. But species and ecosystems unknown to science are well known to local people, whose languages encode not only names for things but also complex interrelations among them.

Packaged in ways that resist direct translation, this knowledge dissipates when people shift to speaking global tongues. What the Kallawaya of Bolivia know about medicinal plants, how the Yupik of Alaska name 99 distinct sea ice formations, how the Tofa of Siberia classify reindeerentire domains of ancient knowledge, only scantily documented, are rapidly eroding.

Linguistic survivorsthe last speakers whom I profile throughout this bookhold the fates of languages in their minds and mouths.

Johnny Hill Jr., a Chemehuevi Indian of Arizona, spent much of his life working in construction and farming. Now retired, he serves as an elected tribal council member of the Colorado River Indian Tribes and works to promote the Chemehuevi language. Designated a last speaker of Chemehuevi, Johnny told his story in the 2008 Sundance documentary film The Linguists .

Raised by his grandmother who spoke only Chemehuevi, Johnny learned English at school seeking a path out of isolation. At the other end of his life span, Johnny finds himself linguistically isolated once again. I have to talk to myself, he explains resignedly. Theres nobody left to talk to. All the elders have passed on, so I talk to myself. Thats just how it is.

Johnny has tried to teach his children and others in the tribe. Trouble is, he says with a sigh, they say they want to learn it, but when it comes time to do the work, nobody comes around.

Speakers react differently to lossfrom indifference to despairand adopt diverse strategies. Some blame governments or globalization, others blame themselves. Around the world, a growing wave of language activists works to revitalize their threatened tongues. Positive attitudes are the single most powerful force keeping languages alive, while negative ones can doom them.

Two dozen language hotspots a term derived from biodiversity hotspots, referring to places where small languages both abound and are endangeredhave now been identified globally. With funding from the National Geographic Society, my effort to map and visit all the hotspots, and to record as many last speakers there as possible, is well under way. Around the globe, numerous scientists and indigenous language activists are mounting similar efforts. But recording is not enough, we must also work to revitalize small languages.