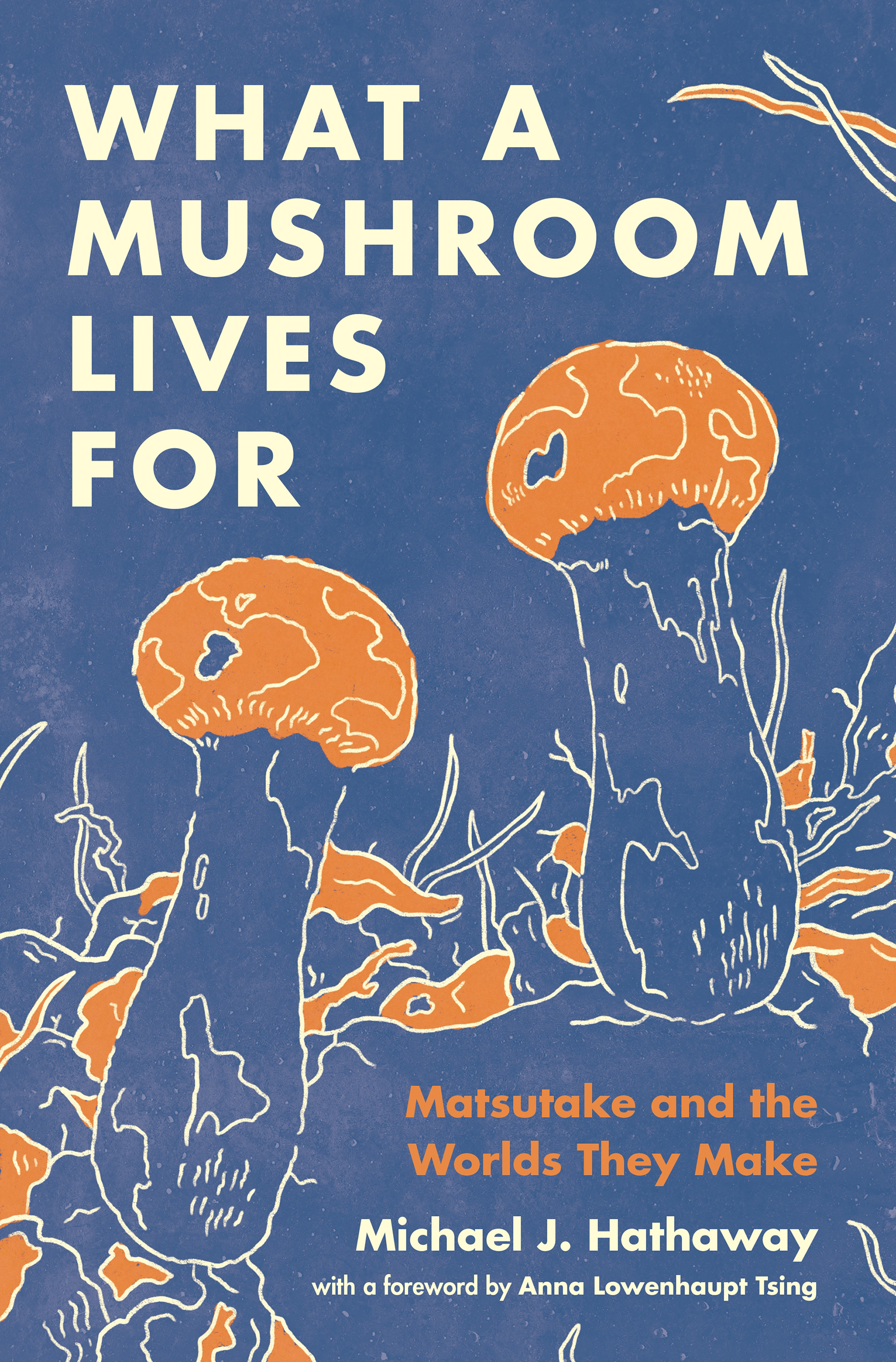

WHAT A MUSHROOM LIVES FOR

WHAT A MUSHROOM LIVES FOR

Matsutake and the Worlds They Make

Michael J. Hathaway

With a foreword by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2022 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hathaway, Michael J., author.

Title: What a mushroom lives for : matsutake and the worlds they make / Michael J. Hathaway.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021034507 (print) | LCCN 2021034508 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691225883 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780691225890 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Tricholoma matsutake. | Tricholoma matsutakeEcology.

Classification: LCC QK629.T73 H38 2022 (print) | LCC QK629.T73 (ebook) | DDC 579.6dc23

LC record available at https: / /lccn.loc.gov/2021034507

LC ebook record available at https: / /lccn.loc.gov/2021034508

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Fred Appel and James Collier

Production Editorial: Ellen Foos

Text Design: Karl Spurzem

Jacket art and design: Karl Spurzem

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Sarah Henning-Stout and Kathryn Stevens

Copyeditor: Kathleen Kageff

And the mushroom hunters walk the ways they walk

and watch the world, and see what they observe.

And some of them would thrive and lick their lips,

While others clutched their stomachs and expired.

So laws are made and handed down on what is safe. Formulate.

The tools we make to build our lives:

our clothes, our food, our path home

all these things we base on observation,

on experiment, on measurement, on truth.

Neil Gaiman, The Mushroom Hunters

CONTENTS

- ix

- xiii

FOREWORD

Fungi! Delicious, dangerous daring? In Michael Hathaways hands, mushrooms come to life not just as objects of human fears and desires but also as makers of more-than-human worlds. Hathaway is curious about the longue dure as well as the contemporary. Why did mammals evolve warm-bloodedness many millions of years ago? How do present-day Tibetans in Yunnan raise funds to revive traditional architecture? These and many more strange and wonderful things about the world turn out to rest on the actions and reactions of fungi.

When Michael Hathaway, Tim Choy, Lieba Faier, Miyako Inoue, Shiho Satsuka, and I formed the Matsutake Worlds Research Group together, fungi were hardly interesting to either scholars or the general public. Perhaps it was the sense that we had stumbled on something fascinating but really obscure that allowed us to completely underestimate the size of the project on which we had embarked. A few months of research, we thought, and perhaps the publication of an edited volume. Many years later, were still at itbut in an entirely different context. Our group has not only produced an edited volume (Matsutake Worlds and Shiho Satsuka, in preparation.) Meanwhile, the climate for reading and writing about fungi has radically changed: now everyone is interested, from chefs to ecologists to public intellectuals.

There are many streams flowing into this river of mushroom fever, and readers will get to explore them in What a Mushroom Lives For. Here are three that matter a lot to me: First, natural history has come alive again in the past decade as a mode by which both scholars and ordinary people connect with the diversity and fragility of the world around us. Suddenly the sex lives of tube worms and the communicative practices of birds hold public attention.

Enlightenment thinkers, we now recognize, underestimated nonhumans in making them appear to be passive resources for human free will. Fungi now greet us from within a newly enlivened and socially active world of nonhumans. This world sparks endless curiosity. Perhaps we are making up for lost time in getting to know the creatures around us.

Second, fungal vitality enters and pushes forward a revolution in biology. Throughout the twentieth century, the modern synthesisthe coupling of genetics and evolutionheld the attention of biologists. Working from the imagined lives of mammals, biologists saw autonomous organisms as representatives of autonomous species. Relations with other species were those of eat or be eaten. Today, this view looks archaic and ideological: interspecies relations of all sorts had been ignored. It turns out that most organisms cannot develop into themselves without working with other species. We humans cannot digest our food without gut bacteria, for example. Fungi are in the thick of this scientific transformation, particularly those fungi involved in mutualistic relations with plants. These fungi bring water and nutrients to plants in exchange for carbohydrate meals. Some scientists think that the only reason trees can form forests is the support they get from mutualistic fungi. Thinking through interspecies relations changes the game entirely for ecology, evolutionary theory, and developmental biology. Evolution, for example, is no longer imagined as a species-by-species affair. Holobionts are multispecies evolutionary units: they evolve together.

Attention to interactions across species also brings history into the heart of ecological attention; interactions are always contingent and historical. History, in turn, opens the door for new forms of interdisciplinary interaction, and this is my third stream. If our object of study is ecological history, we need humanists as well as biologists to trace just how things came out this way. After several hundred years of academic contempt between the humanities and the natural sciences, new avenues of collaboration are becoming visible. Again, fungi have been at the heart of this opening. Fungal histories are a most promising arena for such work across disciplinary divides. Michael Hathaways sketch of the interplay among humans, barley, yaks, oak scrub, and matsutake in Tibetan Yunnan is an example of what becomes possible in this new conversation.

What does a mushroom live for? The first half of Michael Hathaways book presents material on the social lives of fungi, with and without human companions. The latter, that is, the attention to social relations even where no humans are present, is a radical break with much thinking in the social sciences. The field has indeed been coming to terms with the need to integrate nonhumans into analyses of the sociality of humansbut not social relations between one nonhuman and another nonhuman. For many humanistic social scientists, leaving humans out of the scene of sociality raises the specter of a non-reflexive positivism. Anthropologists in particular have spent many years distancing ourselves from this kind of positivism, which can reduce both humans and nonhumans to passive objects of a God-like gaze. Hathaways insistence that mushrooms make worlds by associating with insects, soil minerals, and tree rootsas well as sometimes humanspushes the critique of positivism in a new and provocative direction. To me, it is useful to think with science-studies scholar Karen Barads intra-action, that is, the social encounters through which beings take on form. Fungi