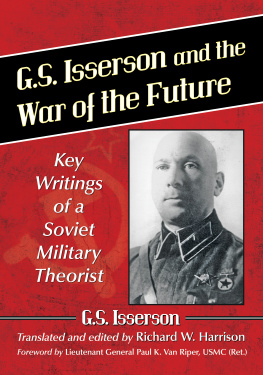

G.S. Isserson and the War of the Future

Key Writings of a Soviet Military Theorist

G.S. Isserson

Translated and edited by Richard W. Harrison

Foreword by Lieutenant General Paul K. Van Riper, USMC (Ret.)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2390-0

2016 Richard W. Harrison. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Brigade Commander Isserson, ca. 193639. This picture may have been taken while he was teaching at the General Staff Academy (courtesy Russian State Military Archives).

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Foreword by Lieutenant General Paul K. Van Riper, USMC (Ret.)

It is my sincere hope that Richard Harrisons G.S. Isserson and the War of the Future will help motivate members of the American defense community to end the prolonged cycle of interest followed by disinterest in Russian military affairs. This unwelcome cycle has hindered the U.S. militarys ability to learn from past Russian and Soviet efforts to develop a theory and practice of operational art. It has also hindered the potential of U.S. military leaders to anticipate undesirable Russian military actions. Scores of defense professionals will need to read and study Harrisons important work if I am to realize this hope. May the following words encourage them to do just that.

Over the past 240 years Americas military interest in Russia has tended to wax and wane with its overall state of attentiveness to Russian affairs. American patriots grew keenly aware of the Russian Empire during the American Revolutionary War, as Catherine the Great chose to carry on trade with the colonists while officially remaining neutral. After the Revolution, American public interest in Russia diminished, only to intensify during the Civil War when Russia offered moral support to the Union and with the purchase of Alaska. Thereafter it declined but rose once more in 1900 as the two nations joined the Eight-Nation Alliance fighting to stem the spread of the Boxer Rebellion in China, and remained elevated as the two nations joined the intense competition for trade in Manchuria. It heightened again in 1905 when the United States mediated the Treaty of Portsmouth that ended the Russo-Japanese War. Over the following years Americans grew less conscious of Russiathat is, until the nation sent its soldiers and Marines to assist the White Army of the antiBolshevik forces during the Russian Civil War. After the Bolshevik victory and establishment of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922, American military concern with Russiathe heart of the matterdimmed again for nearly two decades. Then in 1941 the United States joined with the USSR and the other Allies to fight the Axis powers in World War II. For the next half-century American concern with the military forces of the USSR remained intense. After the demise of the USSR in 1991, the American military gave little thought to the new Russian Federations military except to monitor its activities in Chechnya and its small contribution to the Bosnian peacekeeping force.

Thus, not surprisingly, when Harrisons The Russian Way of War: Operational Art, 19041940 appeared in 2001, establishing his reputation as an authority on the imperial Russian army and the successor Soviet army, hardly any U.S. military professionals considered Russia a threat to international security. These professionals had shifted their focus from the Soviet menace and a parallel interest in operational art to what the 2001 National Security Strategy of the United States of America identified as contemporary threats such as the proliferation of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons, terrorism, and international crime. Professional discussions revolved around global issues and operations other than war. This pivoting of attention was unfortunate, for American military officers had only begun to understand and appreciate the potential of operational art in modern warfare. Moreover, it reflected their general unawareness of the gaps they had in their knowledge of the Russian military, gaps produced by the cycles of attention and inattention to Russia and its armed forces.

Harrisons next book, Architect of Soviet Victory in World War II: The Life and Theories of G.S. Isserson, appeared in 2010. Though the Russo-Georgian War in August 2008 drew the U.S. governments notice along with its ire, it was the war against a global Islamist insurgency and especially the campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq that most concerned the American defense community. Wars of insurgencywrongfully called irregular warscaught the interest of practitioners and theorists alike. Few thought wars involving the fire and maneuver of large, generally similar forceswhat some inappropriately identified as regular warswere likely in the near term. Then as now, they needed to recognize the relevance of this important book, which revealed the profound conceptual thought of a remarkably talented Soviet officer. More important, they overlooked the reality that Issersons intellectual approach and the historical analyses he applied to solving the strategic and operational problems of his age provided a model for answering their own contemporary problems.

Harrisons translated and edited compendium of Georgii S. Issersons major theoretical works, G.S. Isserson and the War of the Future, arrives when the U.S. defense community once more finds itself troubled by Russias recent military activities. Though Russias behavior is disquieting in one way, it is fortuitous in another, for these latest events might encourage defense professionals to study this essential book, as well as its two predecessors, all with great care. Harrison identifies his two Isserson books as companion volumes; thus, we need to read them in tandem.

In the present work, Harrison includes, in chronological order, six of Issersons most important publications on operational art, the first five written between 1932 and 1940, and the last, actually two journal articles, written in 1965. Each of these documents offers members of todays U.S. defense community exceptional insights on the study and exercise of operational art, insights that remain useful despite changed circumstances.

Unless the reader is familiar with personalities and events in the Soviet military during the 1920s and 1930s, I suggest he or she first read Chapter Six, The Development of the Theory of Soviet Operational Art in the 1930s. Written many years after the German army severely tested the theory during the latter stages of World War II, it provides historical context for the other Isserson writings in chapters one through five. In addition, as a primary source for our understanding of the evolution of Soviet military thought, it offers insights on how the U.S. military might advance its own conceptual ideas today.

Although a reader may approach the other five chapters in any order, there is logic to reading them sequentially. To provide a flavor of what they contain as well as to identify some of the elements that have applicability today, I offer the following observations.

Next page