With gratitude for Margaret and Gene,

and hope for Ava and Liza

Introduction

OPRAH

I always knew one day I'd be a guest on The Oprah Winfrey Show.

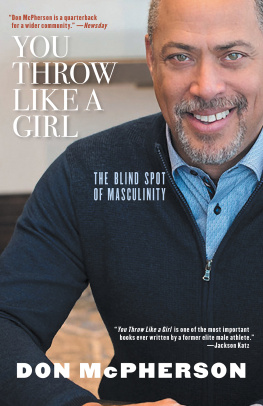

By most accounts, I've lived a charmed life. I was an all-American athlete in high school and college, played seven years of professional football, and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. I come from a solid, closely knit family, the youngest of five children; my two brothers were also professional athletes.

Being on Oprah was consistent with my life's trajectory. But, just as my life as an athlete was beyond my dreams, I also never imagined the subject matter that would bring me to her stage.

I had been invited onto the show to discuss my work of engaging men to prevent men's violence against women. It was a moment of great irony because it was a rebuke of that which made my life as an athlete special. I was an anomaly among men, confronting and dismantling myths about masculinity and sportsthe very things that had lavished me with privilegeand I was there to tell Oprah why this was an essential process for ending all forms of men's violence against women.

My appearance on the show was, in many ways, the vision of my mentor and friend Jackson Katz, who joined me on the show. When I retired from professional football I worked with Jackson, a pioneering voice on masculinity and the issue of men's violence against women. One of the fundamental goals of his work was to challenge existing ideas of masculinity while encouraging men with social status (like athletes) to normalize the conversation and help prevent violence against women.

I wish taking such a stance had been enough to effect real change, but it wasn't. The Oprah Winfrey Show was not the optimal venue to concretely deliver the message fundamental to ending men's violence against women. Nor was simply dismantling my privilege the answer.

I arrived at Harpo Studios a few hours before taping the show and spent most of the time anxiously pacing the green room that was at the end of a long hallway. The early morning silence was broken when a familiar voice, from the other end of the hallway, called out, "It's the O Magazine man!" It was an enthusiastic and iconic tone heard frequently gifting extravagant surprises to exuberant audiences and calling the names of Hollywood's most famous stars. It was surreal to see Oprah Winfrey walking toward me with a welcoming smile. She had just finished her morning workout and walked into the green room with a towel over her shoulder, wearing sweatpants and sneakers and, most notably, no airs or pretense. Her presence was overwhelming and yet she was warm and engaging, just what you would expect from someone who has had such a profound and indelible impact on American culture.

When I walked onstage at The Oprah Winfrey Show on September 23, 2002, I did so confident in my privileged masculinity and fully aware of how I had attained it. I was seven years removed from my professional football career, and over that time I had been immersed in engaging men on the complexities of masculinity and raising societal awareness of men's violence against women. But I was not a confident activist nor a spokesman for masculinity. I was a scared boy hiding behind the facade of cool toughness I had cultivated my entire life as a football player, and now I was trying to use that facade to face questions most men ignored.

I have a clear memory of how that facade was formed. At eight years old, I first attempted to play football. I was the third son and my two older brothers were stars of their age group in our town. I walked onto the field assuming that I would extend the family legacy; I felt as if all eyes were on my every move and that I had to live up to expectations. Anxiously, I stood in line with other boys, determined to catch the ball being thrown at me once it was my turn. But the anxiety was too much to bear and instead of running out to catch a pass, I ran to the parking lot.

The following year, at age nine, I tried again. This time the scrutiny of being a "McPherson boy" was heightened by the fact that my performance, or lack thereof the previous year, was still fresh in everyone's mindespecially my own. This time the drill was a simple handoff and weave through a few cones in the grass. The second attempt ended like the first, with me crying and running off the field to my father's car, in clear sight of our town's entire football community. Compared to the success of my brothers, it was clear that I was quickly becoming a colossal embarrassment. My father gave up trying and I found myself on my own; I had to muster the courage to overcome the cowardice I had readily displayed.

At age ten, I unleashed a talent that usurped my fears. But football did not erase my fears; it was merely the platform that enabled me to demonstrate the kind of masculinity that could disguise my most paralyzing fearvulnerability. I was not fearful of the game of football; I loved to play it. But the performance of masculinity and the inherent expectations that I should ignore and disguise my fears, vulnerabilities, and insecuritiesthat part I had to learn.

For nineteen years, football would provide the stage upon which I mastered the performance of masculinity. In public I thrived, portraying an aloof indifference and proclivity for subtle yet discernible heterosexist attitudes and behaviors. However, internally I struggled with the truth of my dichotomous existence. As I progressed as a football player, the performance grew more grotesque and morphed into absurdity. I achieved social status without being a very social person, with privileges and perks that I neither wanted nor deserved; the respect I received bordered on "fear" that my (violent) physicality was a foreboding force simmering in my persona; I received attention (especially from women and "important" men) that afforded me consideration and inclusion in places from which I would have otherwise been excluded. I became a caricature of privileged masculinity, a "real man"successful, but living by a set of false ideals that belied my authentic identity. Intuitively I understood this, but the privilege it afforded, and the same fears that haunted the ten-year-old me, kept me from thoroughly exploring or dismantling my public persona. I had become comfortable in the myth.

While the Oprah experience was incomparable, it did little to achieve and sustain the ultimate goal of my work: to proactively engage and enlist men in preventing men's violence against women. The approach is rooted in promoting positive conversations with men to expand the fundamental understanding of masculinity, defining it in ways that are affirming but do not perpetuate patriarchy, misogyny, sexism, and violence against women.

At that time, I was trying to find a publisher for what would eventually become this book. During a commercial break, I told Oprah about my book and she immediately responded with the name of a publisher. Within hours of my flight landing at home in New York, I reached out to that publisher and name-dropped one of the most famous and influential human beings on the planet. The manuscript was in the mail the next morning. I was certain that with Oprah's recommendation, the book would be on its way to publication.

The book was quickly rejected. I was told that Oprah's audience didn't need it to understand the issue, and men, for whom this book was ultimately written, would not purchase it. It was a profound rebuff I was not ready to accept at the time. And I found the response to be sexist and condescendingnot to women, but to men. I believed then, as I do now, that men

Next page