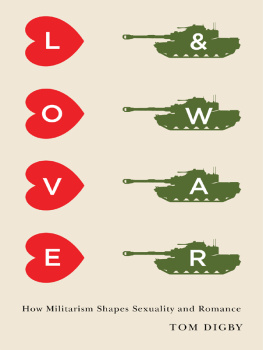

Love and War

Love and War

HOW MILITARISM SHAPES SEXUALITY AND ROMANCE

Tom Digby

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53840-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Digby, Tom, 1945

Love and war : how militarism shapes sexuality and romance / Tom Digby.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16840-3 (cloth : alk. paper) : ISBN 978-0-231-16841-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-53840-4 (e-book)

1. Sex (Psychology) 2. Man-woman relationships. 3. Sex differences (Psychology) 4. Heterosexuality. 5. Masculinity. 6. MilitarismSocial aspects.I. Title.

BF692.D54 2014

155.3dc23

2014008990

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: David Drummond

References to Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

FOR LUNA AND SANDY.

WHATEVER IS GOOD ABOUT THIS BOOK

I OWE TO THEM.

CONTENTS

The conversational tone of this book reflects its origin as a series of talks I was invited to give on college and university campuses. The informality of my writing also reflects an understanding that the world urgently needs philosophers (and other scholars) to write, speak, and teach in ways that can make a difference in peoples lives. That means it is essential for their work to appeal to a broad public audience.

For opportunities to present the ideas in this book to such audiences (in a multimedia format), I am incredibly grateful to Helga Varden (University of Illinois at Champaign/Urbana), Shari Stone-Mediatore (Ohio Wesleyan University), Brook Sadler (University of South Florida), Crystal Benedicks and Cheryl Hughes (Wabash College), Matt Silliman (Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts), and Jen Miller (Millersville University). Thanks also to Jen McWeeny for opportunities to present three of the chapters at meetings of the Society for Women in Philosophy (Eastern). Yet another chapter was presented at an American Philosophical Association session, sponsored by the Society for the Philosophy of Sex and Love, led by the inimitable duo Patricia Marino and Helga Varden. Versions of three chapters were presented at the Women and Society Conference, thanks to coordinators Shannon Roper and JoAnne Myers. Several chapters began as multimedia presentations at the annual International Social Philosophy Conference, sponsored by the North American Society for Social Philosophy.

During the past thirty years my feminist friends have contributed immeasurably to my growth as a person, philosopher, and feminist, especially Luna Njera, Sandra Bartky, Jim Sterba, Valerie Broin, Phyllis Kenevan, Michael Kimmel, Susan Bordo, Alison Jaggar, Naomi Zack, Laurie Shrage, Sandra Harding, Richard Schmitt, Karsten Struhl, Tom Wartenberg, Lisa Tessman, Lynne Tirrell, Kate Wininger, Ann Ferguson, Elise Springer, Sally Scholz, Steven Botkin, Lewis Gordon, Ami Bar On, Sarah Clark Miller, Mary Ellen Waithe, Anita Superson, Joan Callahan, Nanette Funk, Dion Farquhar, Jody Ericson Santos, Ami Harbin, Kristen Waters, Becky Lartigue, Linda Lopez McAlister, Missy-Marie Montgomery, Marty Dobrow, Bobbie Harro, Barbara Love, Laurel Davis, Andrea Nicki, and my incredibly dear friend Jerry Rubenstein.

Margaret Lloyd, who is best known as a poet and artist, has been my dear friend, intellectual comrade, and department chair for seventeen years; many of our conversations manifest themselves in this book; also, she read the manuscript and gave me invaluable comments on it.

My work as a philosopher has been profoundly influenced by my students. I can only mention a few, whose names will have to represent so many others: Sarah Anderson Scafidi, Galo Grijalva, Steve Stoltz, Jon DAngelo, Brian Duval, Chris Malia, Sonya Mickiewicz, Justin Delgado, Lisa Trimbry, Rachel DiSaia Trozzolo, June Coan, Joe Flanagan, Kate Seethaler, and Adam Taylor.

Kit Gruelle, an amazing person who works as an activist against domestic violence, read the manuscript and provided some much-appreciated supportive comments. (Kit is featured prominently in the award-winning, must-see documentary Private Violence.) Markus Gerke, a graduate student working with (and recommended by) Michael Kimmel, read the entire manuscript with great care, giving me a host of both substantive and editorial suggestions for improving both the book and my understanding. Larry Vinson and Robin Cooney are two longtime friends who have been astute, generous, and witty editors and commenters on the manuscript.

I am deeply indebted to Wendy Lochner, publisher for philosophy and religion at Columbia University Press, for her recognition of the importance of this project, for the astute guidance she gave it, and for her sustaining encouragement. Assistant editor Christine Dunbar was a savvy and diplomatic guide through the production process. Susan Pensak was a superlative manuscript editor whose comments led me to rethink some important points and who may have permanently cured me of commaphilia.

Marilyn Frye has influenced my approach to philosophy in many ways, one of which can be seen whenever the word pattern appears in this book, which reflects a more profound influence than might be appreciated by anyone unfamiliar with Fryes methodology.

Under the influence of Janice Moultons articles on adversariality in philosophy, I have striven to use description and explanation, rather than argument, in hopes of making this book an example of non-adversarial philosophy, or as I call it, postmilitaristic philosophy.

The influence of the brilliant philosopher Sandra Bartky can be found throughout this book. I learned from her the usefulness of phenomenology for responding to the pressing needs of the world. Her close and profound friendship has sustained me for over twenty years.

Luna Njera has been the most influential person in my life for eighteen years. She is the most intelligent, perspicacious, kind, generous, and fun person Ive ever known and, to an extraordinary extent, she has made me the person I am today.

You cant stay married in a situation where you are afraid to go to sleep in case your wife might cut your throat.

Mike Tyson

Consider a paradox: In most cultures, heterosexual erotic relationships are favored over same-sex erotic relationships. Heterosexual love is idealized, while same-sex love is often deemed problematic or even reprehensible, primarily on religious grounds. To the extent that any sexual orientation is problematized, it is always a nonheterosexual orientation. But how can heterosexuality be superior to homosexuality, when the former is commonly described as a battle of the sexes? That expression points to a widely shared understanding that heterosexuality is inherently adversarial, so that conflict in heterosexual erotic relationships is inevitable. Isnt it paradoxical that having two persons of different sexes in a relationship tends to make it adversarial, yet that is supposed to be better than a relationship with two persons of the same sex?

I propose that, instead of problematizing same-sex love, we take a look at the problems that appear to be inherent in