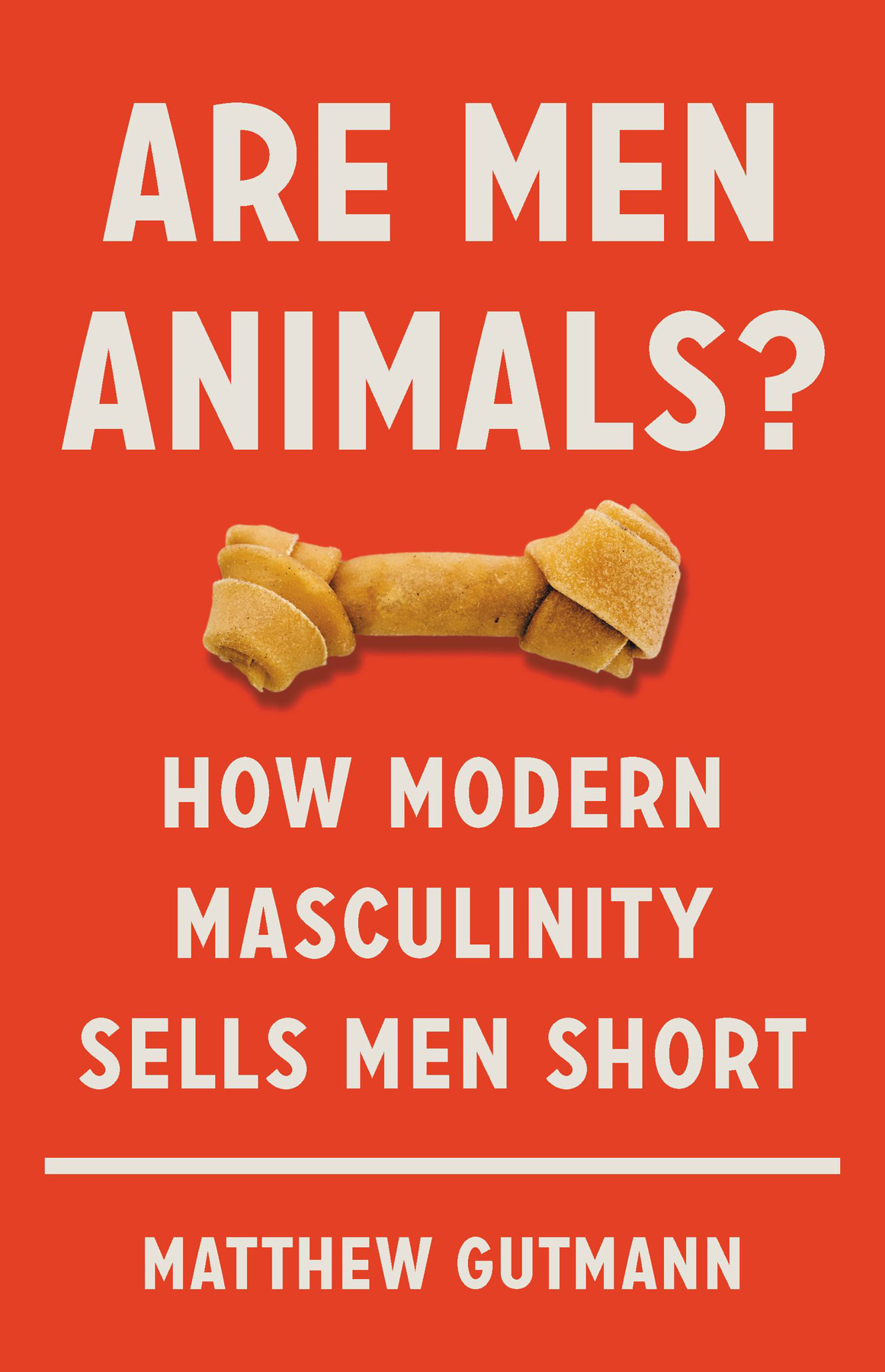

Copyright 2019 by Matthew Gutmann

Cover design by Rodrigo Corral

Cover image Pakorn Kumruen / EyeEm

Cover copyright 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: November 2019

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gutmann, Matthew C., 1953author.

Title: Are men animals? : how modern masculinity sells men short / Matthew Gutmann.

Description: First edition. | New York : Basic Books, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019014412 (print) | LCCN 2019016525 (ebook) | ISBN 9781541699595 (ebook) | ISBN 9781541699588 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Masculinity. | Sex role. | Men--Identity.

Classification: LCC BF692.5 (ebook) | LCC BF692.5 .G88 2019 (print) | DDC 155.3/32--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019014412

ISBNs: 978-1-5416-9958-8 (hardcover), 978-1-5416-9959-5 (ebook)

E3-20191009-JV-NF-ORI

Discover Your Next Great Read

Get sneak peeks, book recommendations, and news about your favorite authors.

Tap here to learn more.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

To my brothers, Rob and Rick

Aint we both members of de same clubde Hairy Apes?

Yank, in The Hairy Ape, E UGENE ON EILL

W E PLACE UNREASONABLE TRUST IN BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATIONS of male behavior. In early 2018, for example, Newsweek carried a story titled Men Who Like Jazz Have Less Testosterone Than Those Who Like Rock. It was an eye-catching headline. Although it relied on ideas we may already have about gender and behavior, it was meant to tease us with a fun bit of new information. Perhaps some readers were ready to accept the conclusion that rock n roll was manlier, because they thought this musical genre was more nakedly belligerent, and testosterone was a hormone they associated with aggressive masculinity.

Other readers might have been pleased by the Japanese study on which the article reported, because it made a correlation between high intelligence and the preference for what the authors considered sophisticated musicclassical, jazz, and world music. But even for the readers who agreed with the conclusion that hard rockers must have more testosterone, there was just one little problem: it was absolute nonsense. The study was based on a minuscule sampling of men. Just how many men had been included in the study they claimed proved a connection between rebellious music such as hard rock and higher levels of testosterone? A grand total of thirty-seven, all young male students in Japan from universities and vocational schools.

This sort of conclusion is all too common. There is a pull on scientists hungry for funding that can lead some to play fast and loose when it comes to research about all kinds of sexy topics, from the effects of caffeine to mind reading to, well, sex. Journalists covering the sciences can feel similarly pressured to embellish the facts based on what they perceive will go over well with their readers. Yet researching the connection between biology and behavior can be dangerous. When journalists jump at the newest alleged association between a biological factor and human behavior, we often gain more insight into preexisting cultural prejudices than into new scientific discoveries. You like rock music? You obviously have a higher level of testosterone, which, as we all know, means you are more of a man. You like jazz? You might be more sophisticated, but you are also less manly.

Uncritical deference to biological explanations of behavior infects our thinking about women as well as men, but in recent decades, women have done a better job pushing back. Most people now understand, for example, that there is no predictable correlation between womens menstrual cycles and their moods. But boys will still be boys, right? Despite decades of research contradicting this conclusion, we are still completely willing to believe that men can best be understood by looking more closely at their brains, balls, and biceps.

Every day people are confronted with biological terms relating to hormones, genes, heredity, and evolution as they try to comprehend male sexuality and violence, as if these biological clues explain what makes men behave the way they do. One particularly effective strategy is to compare the males of the human variety with males of other animal species. When we do this, we tend to simplify the behavior of men to emphasize automatic, animalistic responses to stimuli. There is no room for the enormous range of male responses based on culture, history, and personality, and therefore no need for accountability. (And, lets admit it, that is not being fair to nonhuman males, either.) If we hold that human male behavior is best understood in relation to what the males of diverse species do and feel, driven by instinct and impulse, then we are indeed selling men short. Men are animals. But what does that really mean?

Few people are so blind as to think that biology determines everything about what it means to be a man. But how many of us can claim not to harbor more than a sneaking suspicion that mens physiology explains a lot of their behavior? It is difficult to resist the tidiness of biological answers to lifes big questions. Witness the popularity of the genealogy companies 23andMe and Ancestry.com, which make millions of dollars by indulging peoples beliefs that their DNA tells them who they are, and that their personality and character are somehow rooted in their ancestry.

How we talk about men, even in a casual or offhanded way, determines what we expect of men. Take testosterone. Some of our most widely read and smartest pundits casually endow this molecule with supernatural properties to make broader points about men. A search of daily news sources quickly yields mentions like: a cloud of testosterone (Frank Bruni), hard-driving testosterone-fueled culture (Walter Isaacson), rhetorical-testosterone deficit (Kathleen Parker), testosterone-drenched movie stars (in an article on an up-and-coming young actor), and testosterone-measuring handshakes (Charles Blow). James Lee Burke, one of my favorite mystery writers, leaves an indelible image in a 2016 novel: I could hear him breathing and could smell the testosterone that seemed ironed into his clothes.