Measurement, in one form or another, is one of mankinds oldest and most vital activities. Even before the dawn of civilization, relative measurementtheir tribe is bigger than ourswas vital to the survival of any individual or group. The members of a hunter-gatherer society needed the concepts of more, less and enough (enough time to get home before dark; enough food to ensure that no one will have to go hungry). With the creation of permanent settlements of ever-increasing size such estimation was no longer always sufficient. The increasing sophistication of language allowed comparisons to become ever more complexenough for one person is not always enough for another.

The earliest historical record of a unit of measurement is the Egyptian cubit, decreed in around 3000 B.C.E. to be equal to the length of a forearm and hand plus the width of Pharaohs palm. This is, of course, still rather flexiblemy forearm is not the same length as yours, and since neither of us met Pharaoh, we cannot confidently say precisely how wide his palm was. It is not yet much of a step forward from measuring distance in hand-widths, paces or whatever other approximation springs to mind.

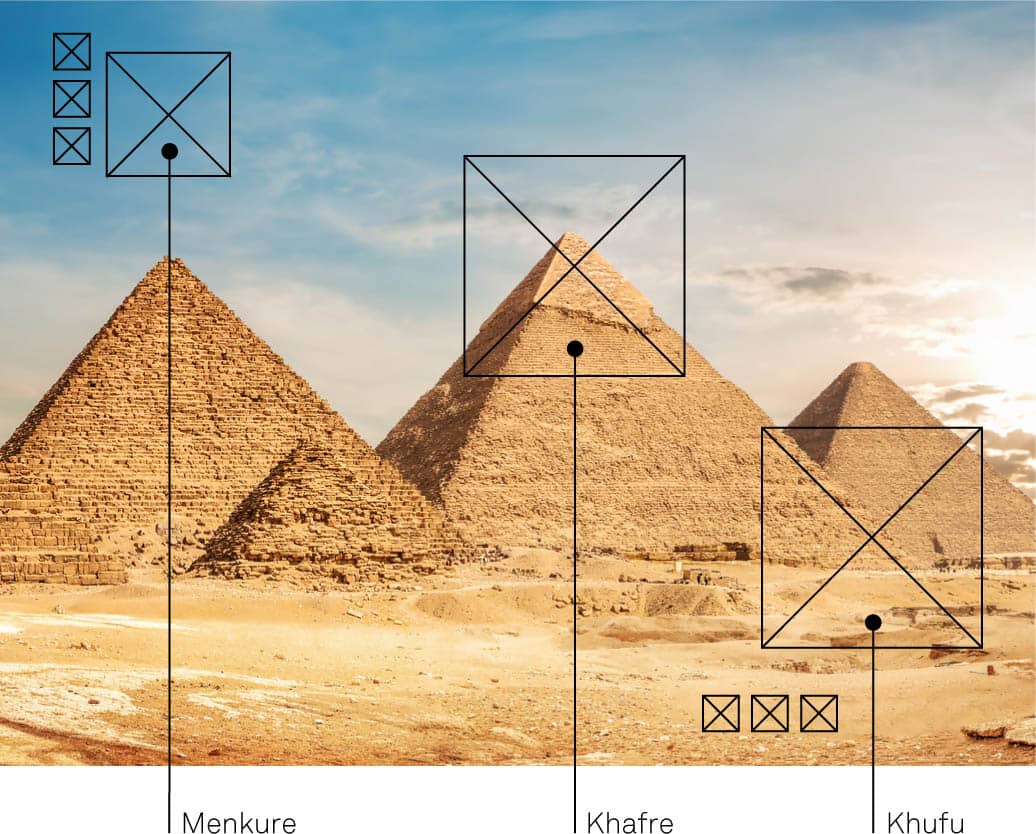

The pyramids at Giza in Egypt are geometric constructions of astonishing accuracy, even if the symbolic meaning of their proportions is not fully known. The largest of the three, Khufus pyramid, remained the tallest manmade structure on Earth from its construction before 2500 B.C.E. until the 19th century more than 4,300 years later.

By 2500 B.C.E., however, the complicated and rather imprecise definition had been simplified drastically: a cubit was the same length as the prototype royal master cubit, a black marble rod some 52 cm in length. From this simple model it becomes possible to measure distances, areas, and volumesand even masses in comparison with a volume of a specified substances such as gold or water.

While accurate measurements revolutionized aspects of human life ranging from craft and architecture to trade and transportation, the most important change they brought about was the possibility of science. Without accurate measurementand equally accurate recordingno useful form of science, engineering or technology is really possible. Without accurate measurement, you couldnt be holding this book in your handsa modern printing press is a huge piece of precision machinery.

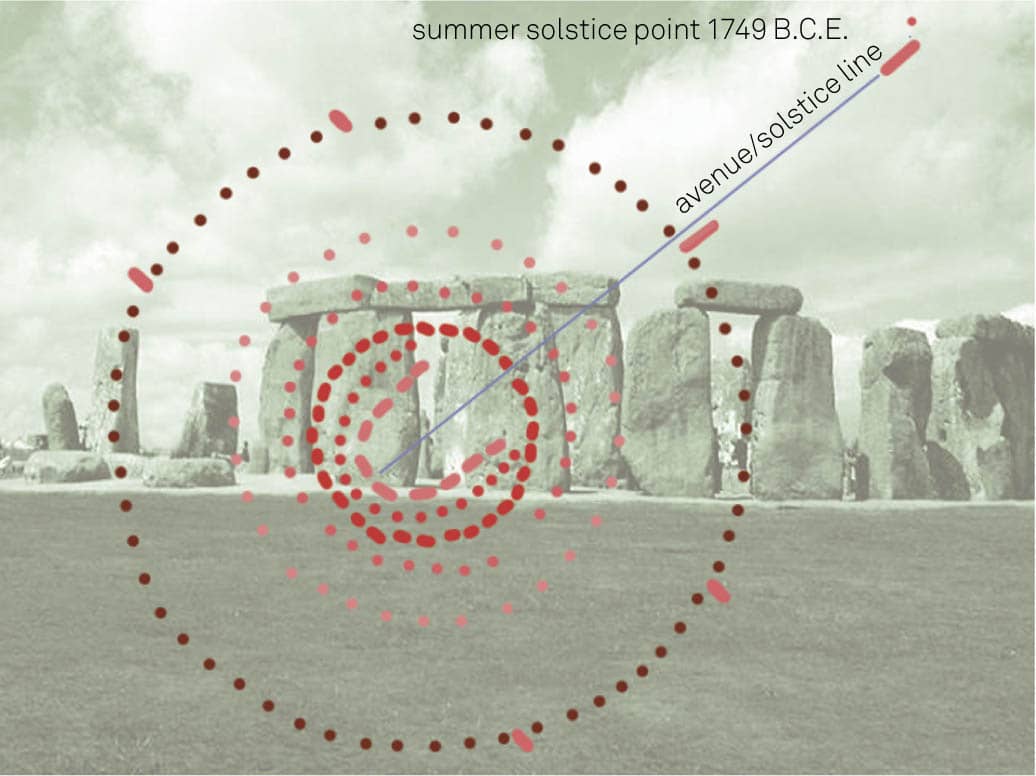

One of the first application of this science was in measuring the heavens and refining calendars and timekeeping. Evidence of astronomical record-keeping dates back thousands of yearsnot just to literate civilisations like ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, but also to the prehistoric stargazers of north-western Europe who erected monuments like Stonehenge with astonishing precision.

The influence of these early peoples and in particular those great engineers the Romans, can still be felt today, in an wide variety of ways. We owe to the Romans many of the names of our traditional unitsand their language has also been plundered for scientific terms. Ounce and inch both derive from the Roman uncia, meaning a twelfth. Uses of uncia were not limited merely to weight and distance, however. Almost anything could sensibly be divided into 12 parts, and almost anything (at one time or another) was. To a Roman it made perfect sense to talk of unciae of a cake, or an estateperhaps even a business with ownership divided among several people.

Although the famous bluestone slabs arrived at Stonehenge in the west of England from Wales in around 2500 B.C.E., the earliest similar construction on the site is believed to have been built some 600 years earlier.

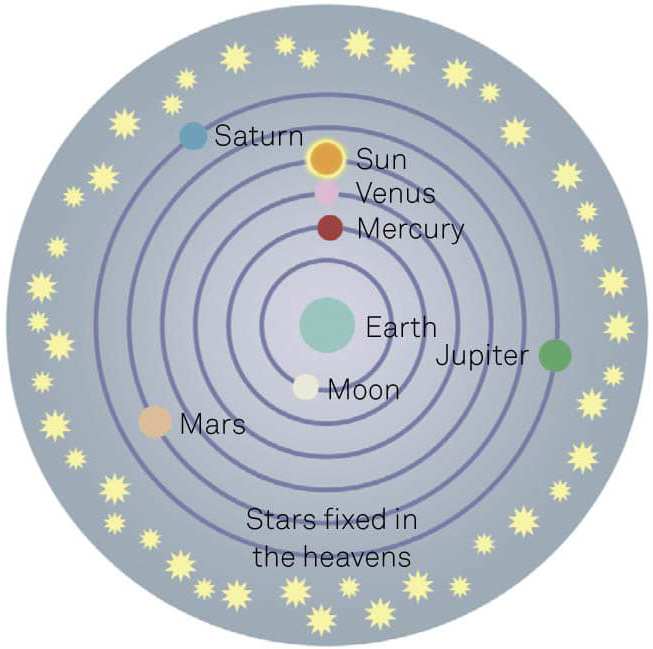

Ptolemaic system

In his astronomical treatise Almagest, one of the most influential books of Antiquity, Ptolemy compiled the astronomical knowledge of the ancient Greek and Babylonian world. This geocentric model of the solar system remained the generally accepted model in the western and Arab worlds until it was superseded by the heliocentric solar system of Copernicus.

For centuries after the fall of Rome, systems of customary units remained largely unchanged; there was, after all, little new to measure. Still, the feudal monarchs of Europe were interested in measurement for the same reason that any government is: if you do not know what someone owns or produces, how can you tax them on it?

As the Renaissance reinvigorated progress in art and science, however, interest in measurement regained some of its former vigor. Traditional units, however, continued in usesometimes more different from one town to its neighbour than they were from one century to the next. Steadily, though, they became more accurate and reliable. Candles with hour markings were replaced by clockwork. While a clock in one town might tell a different time from that in a town 20 miles away, identical clocks could at least be relied upon to keep each hour to the same length.

Then came the French Revolution, and the great reform heralded by the introduction of the metric system. Though initially unpopular even in France, this system was the logical measuring accompaniment to the decimal Arabic numerals that had by then firmly supplanted Roman numbers throughout Europe. Decimal numbers made calculations of all kinds far more straightforward, as well as greatly simplifying much mathematical thinking. Trade and measurement, however, was another matter: 10 sheep were 10 sheep, but a pound was still 12 ounces. Conversions between different types of measurement were more complex stillif one pint of something weighed one pound, one gallon of it most definitely did not weigh one stone. The metric system supplanted all of this with a system of related units, distinctions of scale being made purely by the use of prefixes to indicate the magnitude of the number.

The standard unit forming the base of this system, from which all of the others were initially derived, was the meter. It was defined as one-ten-millionth of the distance from the Equator to the North Pole along a meridian passing through Paris (in a steady curve at a theoretical sea level, rather than along the less-than-smooth surface of Earth). An enormous survey was carried out at great expense to calculate this distance as accurately as possible, and a platinum-iridium barthe equivalent of Pharaohs master cubitcast as a permanent record. Carefully manufactured duplicates were distributed throughout Europe (and, ultimately, the world) to ensure that everyone was using the same meter.