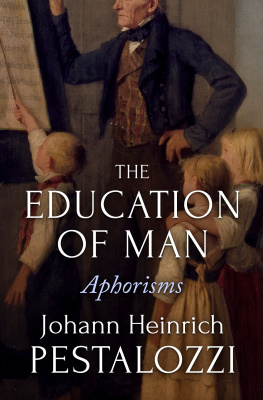

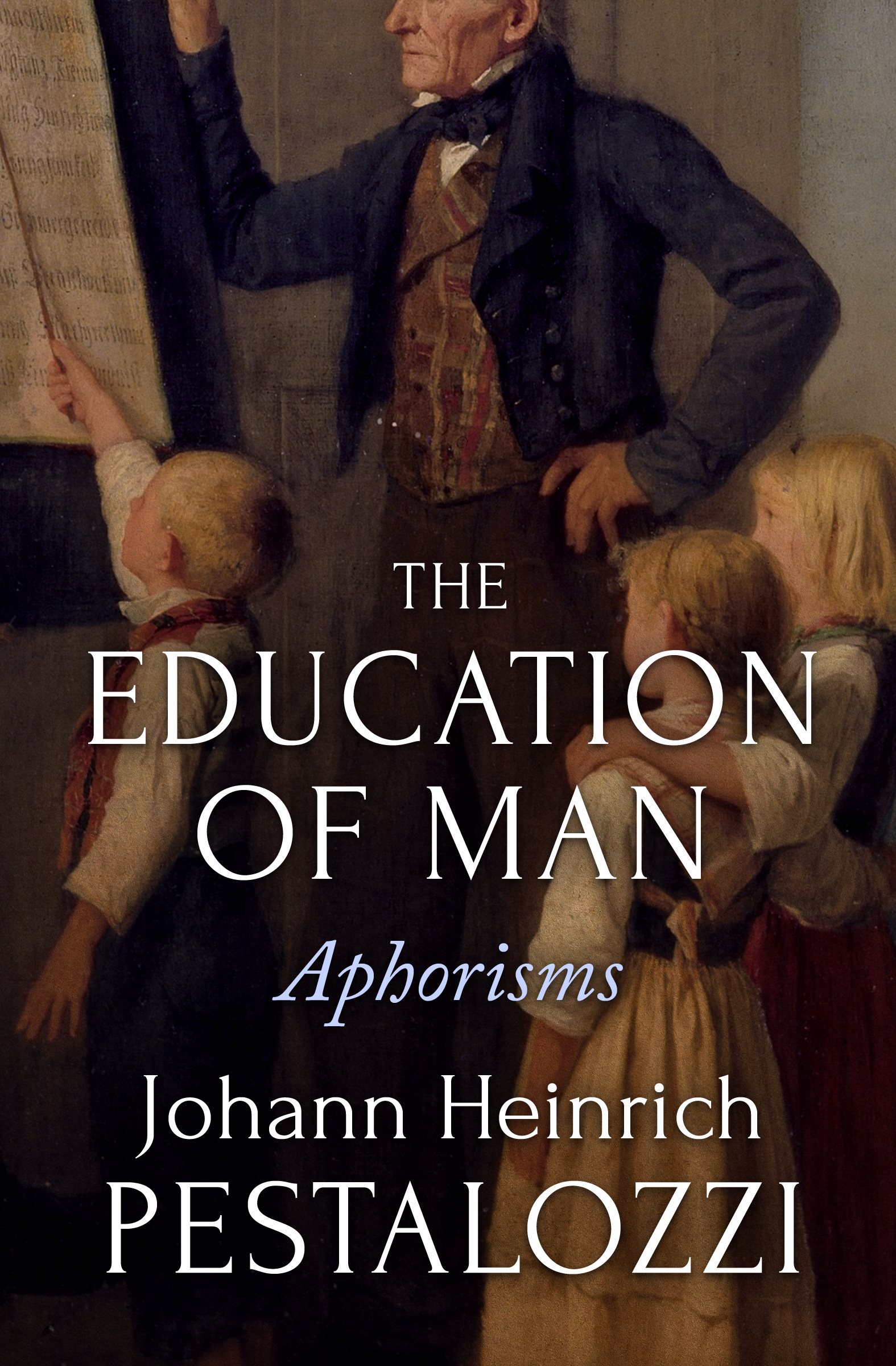

PESTALOZZI AND THE ORPHANS IN STANS

Oil painting by A. Anker, 1870, in the possession of the Kunsthaus, Zurich

COURTESY PESTALOZZI FOUNDATION OF NEW YORK

THE EDUCATION OF MAN

HEINRICH PESTALOZZI

PESTALOZZI AS EDUCATOR

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (17461827) was in his day the worlds most widely acclaimed teacher of the young. Today it seems further fair to assert that Pestalozzi stands out as the one man who more than any other in educational history succeeded in shifting educational aims and procedures from a long prevailing faulty pattern to a distinctly different pattern which has since brought outstanding better results and still promises indefinite growth.

No creation comes from a vacuum. Pestalozzi was a child of the eighteenth century Enlightenment, that movement which in America produced Pestalozzis close contemporary, Thomas Jefferson (17431825). As Jefferson, the advocate of political freedom and equality, wrote our Declaration of Independence and later guided free America along the line of its democratic respect for individuality, so Pestalozzi carried the same Enlightenment spirit of equality of opportunity and respect for human personality into the schoolroom, where beforetimes these had been conspicuously and sadly lacking.

Three things in the school practice of his time deeply stirred Pestalozzi: first, that the children of the poorest were in effect excluded from education; second, that in school a superficial verbosity, as he called it, characterized pupil recitation, they hardly knew the meanings of the words they recited and accordingly failed both in spirit and in fact; third, that these children were flogged unmercifully for failing even though the failure was not their fault. It was these three school practices that Pestalozzi directly attacked.

Six principles eventually emerged for Pestalozzi as he sought to remake the school effort. (The wording here except in direct quotations is of our day.)

1. Personality is everywhere sacred. This constitutes the inner dignity of each individual, for the young as truly as for the adult.

2. As a little seed contains the design of the tree, so in each child is the promise of his potentiality. The educator only takes care that no untoward influence shall disturb natures march of developments.

3. Love of those we would educate is the sole and everlasting foundation in which to work. Without love, neither the physical nor the intellectual powers will develop naturally. So kindness ruled in Pestalozzis school; he abolished floggingto the amazement of all outsiders.

4. To get rid of the verbosity of meaningless words Pestalozzi developed his fundamental doctrine of Anschauung , direct concrete observation, often inadequately called sense perception or object lessons. In his school no word was to be used for any purpose until adequate Anschauung had preceded. The thing or the distinction must somehow be seen or felt or otherwise observed in the concrete. Pestalozzis followers developed from this the commonly recognized principles: from the known to the unknown, from the simple to the complex, from the concrete to the abstractprinciples which the pre-Pestalozzian schools tragically disregarded.

5. To perfect the perception got by the Anschauung, the thing must be named, and appropriate action must follow. A man learns by action have done with [mere] words! Life shapes us and the life that shapes us is not a matter of words but action.

6. Apparently out of this demand for action came an emphasis on repetitionnever blind repetition, repetition of action following the Anschauung. (This particular repetition as used by Pestalozzi seems to us now undesirably formal.)

Pestalozzis school run on these principles attracted wide attention and at its height brought him great fame. Many famous people and inquiring minds came to see the school with their own eyes. Strange in that day was it to see a school succeed, succeed greatly, where there was no whipping and real friendliness held between master and child, with self-activity on the part of the pupils and great interest in all they did. It was literally true that those who came to scoff returned to praise. Many were the ambitious young men who came to study with Pestalozzi, two of whom later greatly influenced American education, Froebel (17821852) and Herbart (17761841).

Historically, the greatest single effect from Pestalozzi influence was on the Volksschule of Prussia. After the downfall at Jena (1806) Prussia made a determined effort to create a new life. Wilhelm von Humboldt, a great scholar and statesman, was put at the head of education. On the advice of Fichte that Pestalozzis method was the only suitable one to use, a number of Prussian young men were sent thither with instructions to give themselves completely up to the life and pedagogical activity which are nowhere so busy as there. These young men did as they were told and returned to Prussia to remake the Volksschule and to institute seminaries for teacher training. The result was that the world at large came to look upon these Prussian schools as the best anywhere to be found. The French philosopher, Victor Cousin, made (1831) a careful study of these Prussian schools and seminaries and wrote a report which had great influence on the French educational reconstruction of 1833. This report was translated into English and spread widely through the United States. The husband of Harriet Beecher Stowe, Calvin Ellis Stowe (1837), and Horace Mann (1843) also made reports of their study of the Prussian schools. It seems safe to affirm that the great remaking of American education from 1830 to 1860 came directly or indirectly from Pestalozzi, much of it by way of Prussia. From this source came our first normal schools. From Pestalozzian influence the American schools took on geography, music, art, gymnastics; arithmetic teaching was remade to be understandable by children; the word method of teaching reading supplanted the cumbersome old alphabet method; whipping was increasingly abolished.

Various persons brought the Pestalozzian school methods to America. Joseph Neef (17701854), who had taught with Pestalozzi, was brought to America to teach these methods. He taught in the East and the Middle West from 1806 to the time of his death. The Western Literary Institute, of which Calvin Ellis Stowe was a member, worked from 1831 at extending the general Pestalozzian outlook. More widely known was the Oswego movement, a systematic effort in the third quarter of the century to spread the better features of Pestalozzianism. Helping Dr. E. A. Sheldon in this was Herman Krusi, Jr., son of Pestalozzis most famous assistant of the same name. It has been claimed that the culminating point of Pestalozzian influence in this country was reached when William T. Harris introduced its method into the St. Louis public schools during his superintendency of 186780. In the judgment of this author, however, a higher point was reached at Quincy, Massachusetts, 187680, under Colonel Francis W. Parker. This was pretty certainly the highest point before Herbartianism was introduced about 1890 and Deweys influence began about 1895.