Contents

Guide

Page List

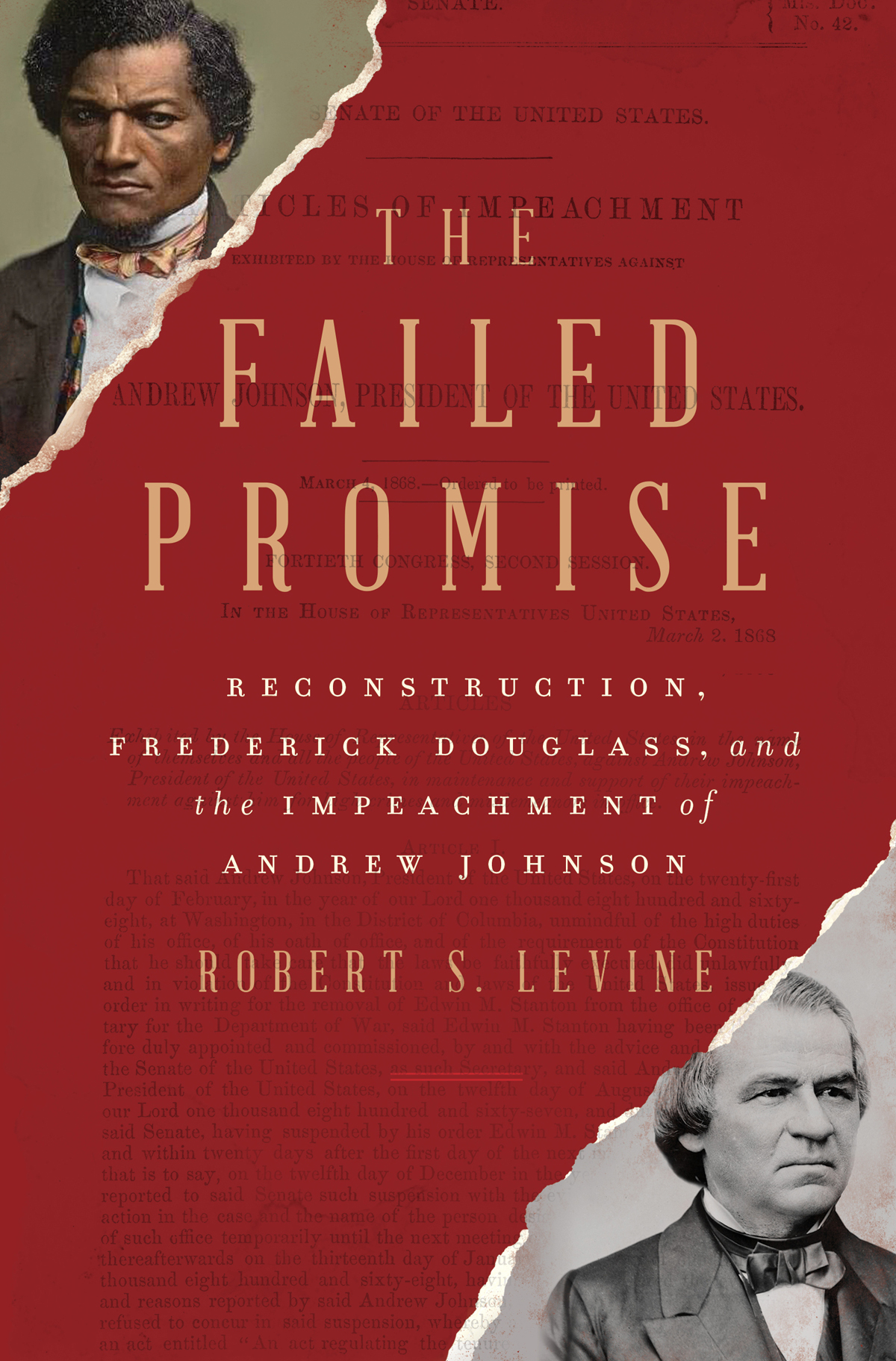

THE

FAILED

PROMISE

R ECONSTRUCTION ,

F REDERICK D OUGLASS ,

and the I MPEACHMENT of

A NDREW J OHNSON

Robert S. Levine

In Memory of My Beloved Sister Karen Levine (19602020)

CONTENTS

A NDREW J OHNSON took the oath of office and assumed the presidency on April 15, 1865, hours after Abraham Lincoln died from his assassins bullet. Almost three years later, on February 24, 1868, Johnson was impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives for high crimes and misdemeanors. It was an event no one would have predicted on the day of his inauguration.

Johnson was an anomaly among southern political leaders. He had opposed southern secession after the 1860 election of Lincoln, and during the Civil War he had called for the end of slavery. In 1864, as military governor of Tennessee, he announced to a large gathering of Blacks in Nashville that he had ended slavery in his home state. Seemingly more radical and progressive than the president himself, Johnson looked like the ideal person to serve as Lincolns vice president.

When the Civil War ended, the country was poised for great changes. Slavery had been abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Hope abounded, at least in the North, about the possibility of bringing forth a more egalitarian nation through what was already being called Reconstruction. Lincolns Republican Party took the main responsibility for Reconstruction after his death, and those on the partys most progressive wingsuch as Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, and Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohiohoped to transform the erstwhile slave South into a region where the freedpeople could vote, find work, own property, and have the same rights and privileges as white people. These leaders, the Radical Republicans, initially regarded Andrew Johnson as the best possible president to lead the nation. But they soon learned that Johnson had an altogether different understanding of Reconstruction. Johnson believed that the president, not Congress, should be overseeing the process, and that the main goal of Reconstruction should be to restore the ex-Confederate states to the national body with no essential changes mandated by the federal government, except for the abolition of slavery.

The conflict between Johnson and the Radical Republicans on the meaning of Reconstruction began less than a year after Johnsons inauguration. It quickly dominated national political debate, and it culminated in the first impeachment of a U.S. president. When the impeachment trial concluded in May 1868 with the acquittal of Johnson, three years had passed since the end of the Civil War. By then, the odds of creating a reconstructed United States as imagined by the Radical Republicans had greatly diminished.

May 1868 lay far in the distance on Johnsons inauguration day. Even with the shock and mourning at the assassination of Lincoln, Republicans had high hopes. But the promise of Reconstruction began to fade just a few months into Johnsons presidency, and by late 1868 one could already talk about its failure. This book charts the course of Reconstruction, from the optimism of the spring of 1865 to the increasing pessimism of the late 1860s and 1870s, from the perspective of a man who was not a senator or congressman, and was not directly involved with the political conflict between the president and Congress. That man is the great African American leader Frederick Douglass.

Douglass was forty-seven years old in 1865, when Johnson took office. He was actively advancing his own vision of Reconstruction. Like the Radical Republicans, Douglass argued for Black male suffrage and federal programs that would help the freedpeople gain education, employment, property, and equal rights as U.S. citizens. He viewed the Radical Republicans as the friends and supporters of Black people, though he became wary when they didnt move quickly or boldly to address racial inequities. For a few months in 1865, he may well have considered Johnson as potentially the right leader for the times. But by late summer of 1865, Douglass was disillusioned, and as the Johnson presidency wore on, he gave numerous lectures and published essays challenging Johnson. He even met with the president at the White House to make a case for Blacks civil rights.

During the Johnson years, Douglass undertook a series of rescue missions in an effort to sustain the kind of Reconstruction that he thought would best serve the interests of Black people. These missionslectures, meetings, strategic publicationsmeant constantly watching, or shadowing, Johnson, which Douglass did for the full four years of Johnsons presidency. Johnson did the same for Douglass, for he recognized that he could not ignore this prominent Black critic of his administration. Ive intertwined Douglasss career with Johnsons presidency to provide a new view of Johnsons impeachment and the promise and failure of Reconstruction itself.

When I began this book on Douglass and the impeachment of Andrew Johnson, I noticed that even the very best works on the impeachment focus mainly on the Radical Republicans. Black voices are almost entirely absent, with Douglass providing only occasional cameos. But Douglass had a sustained interest in Johnson from 1865 to the time of the impeachment, and his perspective wasnt always in accord with that of the Radical Republicans. It is certainly worth celebrating the idealistic Republican congressmen who defied the president in order to bring equal rights to the freedpeople. That is a compelling story, but its not the full or only story that we can tell about the impeachment. We need to consider Douglasss perspective more fully. Among other things, it helps us to see some of the limits of the Republicans.

Douglass was not the only African American leader who called for a radical, multiracial Reconstruction and contested Johnsons limited, top-down vision. Because of the attention given to the Radical Republicans, the voices of other African Americans, not just Douglasss, have been neglected. Many of these Black leaders collaborated with Douglass at Black conventions, spoke with him at lecture venues, and wrote for newspapers and periodicals. This book emphasizes Douglasss responses to Johnson, but it also includes discussion of other key African American critics of Johnson, such as George T. Downing, Frances Harper, Douglasss sons Lewis Henry Douglass and Charles Remond Douglass, Philip A. Bell, and the anonymous contributors to the Christian Recorder, the most widely read African American newspaper of the period. I also consider Black leaders such as John Langston and Martin R. Delany, who thought Johnson wasnt all that bad, at least for a white president.

African American leaders had called for a transformative Reconstruction since the beginning of the Civil War. As I became interested in recovering a Black perspective on the impeachment of Johnson, the book grew beyond its initial focus on the impeachment. I wound up telling a more comprehensive story of Douglasss and other African Americans efforts to articulate what they saw as the promise of Reconstruction and the problem with Johnson.

Johnsons impeachment remains central to this book. I follow Johnsons career as it unfolds from the day of his inauguration, and I trace the engagement of Douglass and his African American contemporaries with the events leading to the impeachment. In doing so, I attempt to move African Americans from the background to the foreground of the four years of Reconstruction under Johnson. At an 1865 meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society, the veteran Black abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond (the namesake of Frederick Douglasss son Charles Remond) remarked that it was utterly impossible for our white friends, however much they have tried, fully to understand the Black mans case in this nation. Through Douglass and his compatriots, I have tried to convey African Americans case against Johnson, and even the Radical Republicans, in the years immediately after the Civil War.